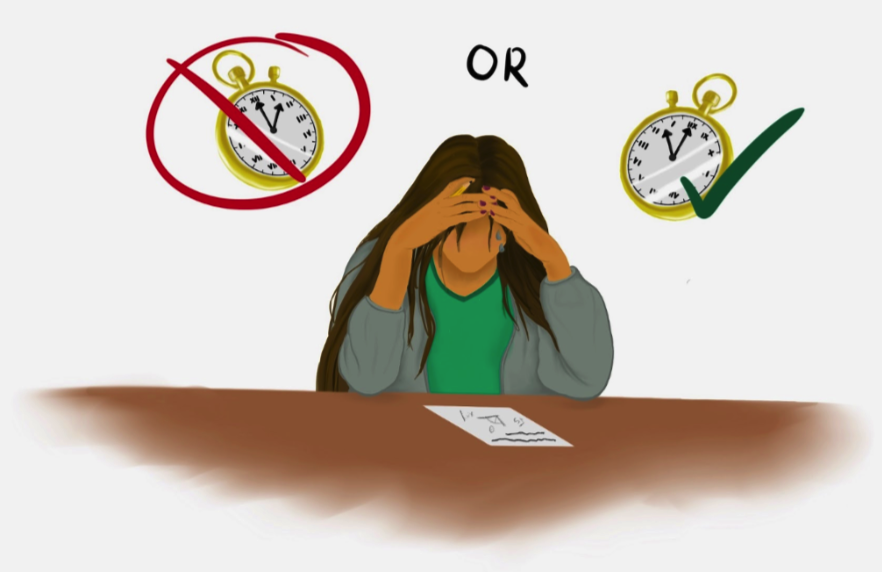

Everyone learns differently, and therefore, accommodations are necessary to give students with learning disabilities the same chance to succeed as their peers. Accommodations such as extra time for timed assessments allow students who have difficulty concentrating to demonstrate all that they know. But wealthier students are disproportionately more likely to have accommodations compared to lower-income students. According to The New York Times, public school students from families that are in the top 1% of income are more than twice as likely to have accommodations as the average public school student. Private school students have even higher rates. To make learning more equitable, accommodations should be expanded for lower-income students so that all students with learning disabilities can succeed. At public schools, many families need more guidance in understanding how to help their child get accommodations. And at private schools like Poly, lower-income students deserve a more affordable option to receive accommodations directly through the school.

There is a striking difference between the number of students with a learning disability at private colleges and public community colleges. According to The Atlantic, 38% of undergraduate students at Stanford have accommodations. However, only 4.6% of students at a California Community College got assistance from the Disabled Student Programs and Services. This disparity has caused people to question the system of accommodations. According to The New York Times, “While experts say that known cases of outright fraud are rare, and that most disability diagnoses are obtained legitimately, there is little doubt that the process is vulnerable to abuse.” But overall, wealthier students with accommodations do have a learning disability. Instead of taking away accommodations from wealthier students, it should be easier for lower-income students to get them.

504 plans legally ensure that all public school students, in addition to students at a private school with national funding, can go through testing for accommodations. Public schools offer testing through a psychologist employed by the district. However, many families do not know about this system, which is not publicized at their schools. Families that are more concerned about college are often more likely to help their children get accommodations, but this is not to say that these students do not qualify. Also, wealthier families can pay for private testing if they have trouble receiving accommodations from their public school.

The system for accommodations is different for private schools. Poly does not have a psychologist who tests for accommodations, meaning students go through this process with a psychologist outside of their school. While learning specialists at private schools like Poly may meet with parents before getting tested to provide recommendations for a doctor, they do not directly play a role in conducting the evaluation.

For students who receive financial assistance at Poly, affording the tests is unfeasible. While pricing varies, testing for accommodations can cost between $3,000 and $10,000, according to The New York Times. Oftentimes, insurance companies do not cover this price, especially for students who have not previously been diagnosed with a learning disability like ADHD, but still may be eligible for accommodations. While some families can afford these prices, lower-income families – or, for that matter, many middle-income families as well – have a hard time affording testing for their children. According to the school’s website, “Polytechnic School has been committed to sustaining a financial aid program to make a Poly education accessible to families from all socioeconomic backgrounds.” However, there is inequity in terms of accommodations, which impacts educational success.

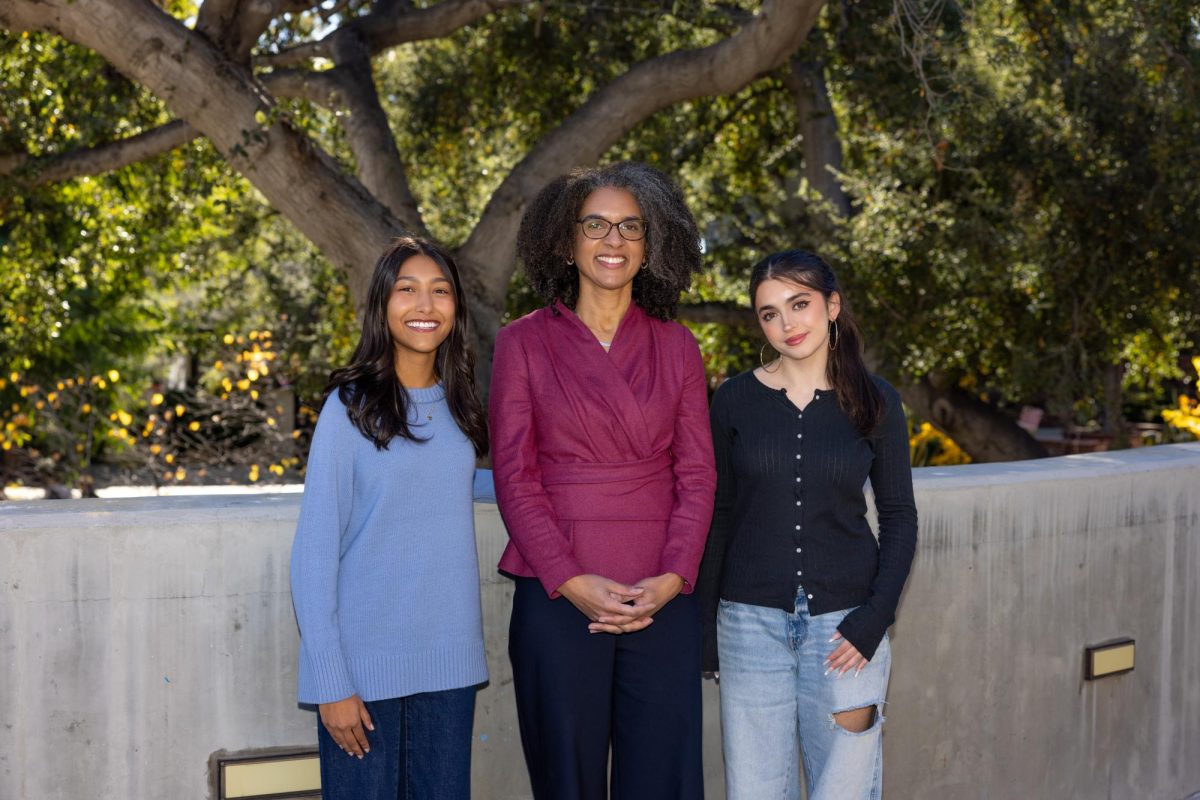

“I do definitely see an issue of equity there, and I recognize that,” said Upper School Learning Specialist Maya Seneus. “That said, there are so many pathways to an evaluation. And so I think it really is just figuring out the best fit for the individual family and their circumstances.”

Yet it is unclear what these different pathways are. Poly certainly does not provide alternative options for students to get testing. And while each psychiatrist has their own pricing for accommodations, the process is rarely inexpensive.

Making accommodations more equitable varies based on the school. For public schools, there is often a lack of information and knowledge about testing, so parents should be given more information and guidance on helping their students get accommodations. At private schools, the issue is affordability. Insurance companies could help with this by covering the price of testing for families. But a more probable solution is that private schools can hire psychologists to test students for free in the way that testing at public schools works. Poly could hire someone to test students part-time, focusing on helping lower-income students who are receiving financial assistance. While families would still have the option to test privately, they would not be obligated to pay the hefty price anymore.

Why has this not happened yet?

“I know staffing in general is tricky to figure out the balance of what resources we do have, what resources we need and how to go about that,” says Seneus. But if public schools can afford to hire a psychologist, a school with as many resources as Poly should be able to do the same. Besides, Lower and Middle School Psychologist Clint Daniels, Psy.D., who already works at Poly, could have an expanded role where he tests for accommodations. His clinical specialties include anxiety and ADHD, and Daniels is qualified to administer these exams as a Doctor of Psychology.

The popularity of accommodations in schools shows a new emphasis on helping all students learn successfully. But only once every student can access these resources will equity be reached.