On Monday, Oct. 28, we, as The Paw Print Editors-in-Chief, organized an Upper School-wide assembly, titled, The Making of a Presidential Candidate, in collaboration with the Community Forum initiators: Film Teacher Adam Feldmeth, Science Teacher Will Mason and College Counselor and 11/12th Grade Dean Garine Zetlian.

The assembly featured an interview with Upper School Coordinator Ryder Livingston, History teacher Avi McClelland-Cohen and former congressional candidate Ben Samuels ‘09.

From 2009 to 2017, Livingston served in the LA district office for former Senator Barbara Boxer, fielding constituent phone calls, managing mail and collaborating with the U.S. Marshals to monitor potential threats. In 2016, he worked with then-incoming Senator Kamala Harris’s team to prepare the LA office for her administration’s arrival.

McClelland-Cohen, who teaches AP United States History and Government and Politics at Poly, interned for Rep. Jan Schakowsky and worked as an organizing fellow for Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign. She also worked to shape federal foreign policy at Peace Action, a nonprofit interest group focused on diplomacy and nuclear disarmament.

Samuels is the founder of Samuels Advisors and has worked with politicians across political parties with bipartisan appeal, such as then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel, a Democrat, and former Governor Charlie Baker, a Republican. In 2022, he ran for Congress in Missouri’s 2nd Congressional District, ending his run when Missouri’s legislature drew his own house out of the district he was hoping to represent.

The assembly provided the Poly community with an insider’s view of domestic politics and governance. Each panelist brought their own, distinct perspective to the conversation, underscoring the multifaceted nature of political involvement. At the same time, the three panelists all emphasized the importance of upholding democratic values that encourage critical thinking, civic engagement and open dialogue.

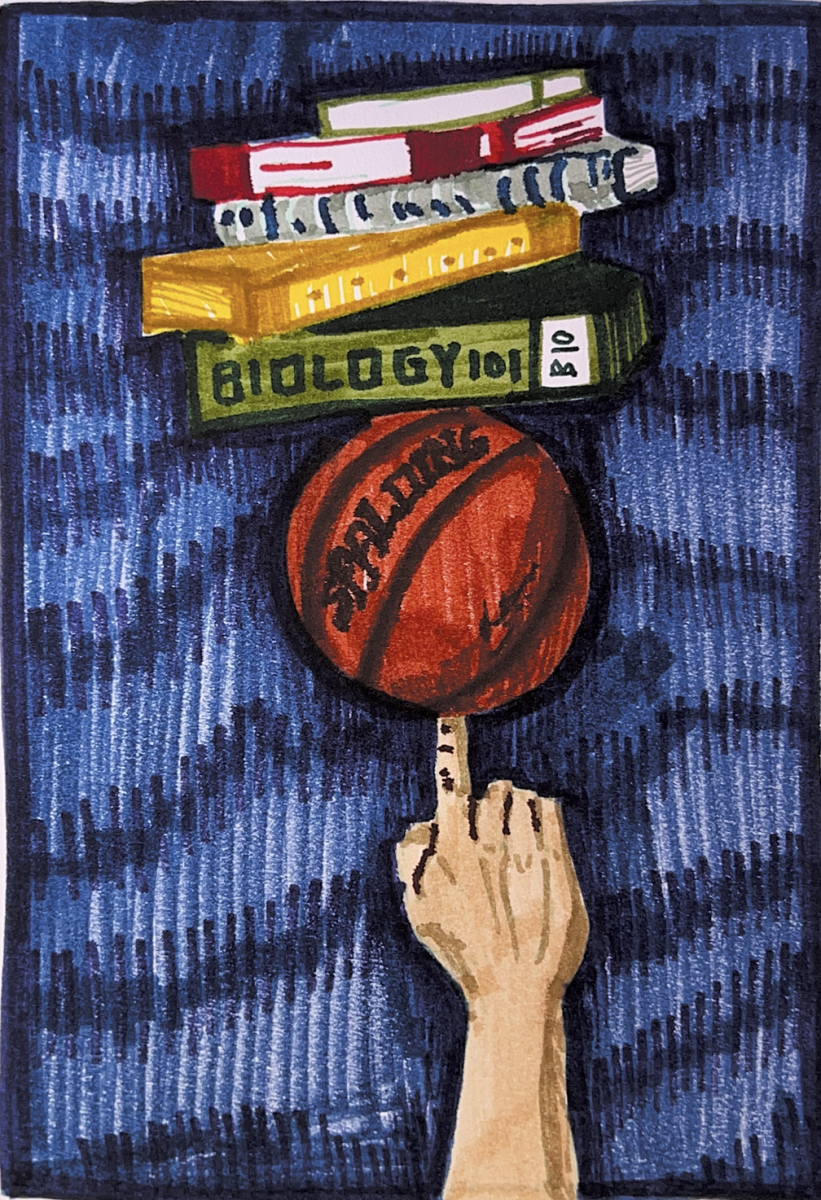

For Samuels, Poly served as a launchpad for his career. His experiences as a former editor-in-chief of The Paw Print as well as on Poly’s debate team, made entering the obfuscated and divisive world of politics easier. The thick skin and necessary skills he developed as a journalist such as reporting diverse viewpoints and daylighting uncomfortable truths prepared him for the criticism that was to come with running for office.

McClelland-Cohen’s reflections on her formative experiences conveyed to students the snowball effect of local actions. From accompanying her father when driving voters to polling stations and witnessing the rise of political leaders like Obama, McClelland-Cohen’s experiences offered inspiration for students looking for ways in which they can partake in their country’s government despite not being old enough to vote. Moreover, she stressed the necessity for voters to hold elected officials and parties accountable not just during elections but while they are in office as well.

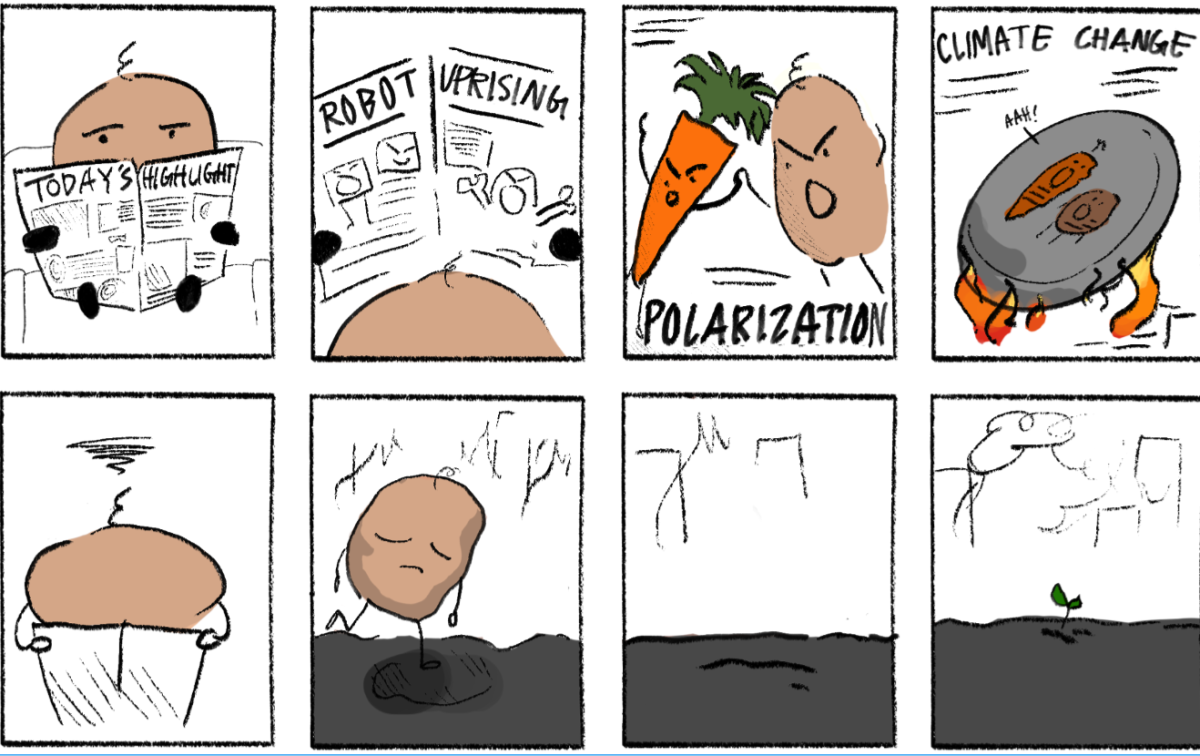

Livingston’s experiences working in government highlighted the distinction between politics — how power is gained — and governance — how power is wielded to create change. He highlighted how the landmark Supreme Court decision Citizens United v. FEC has enabled unlimited campaign spending from wealthy donors and interest groups, increasing political corruption, as well as how digitized media has given rise to polarization. Despite these concerns, however, Livingston urged students to engage with politics openly and optimistically.

Altogether, as the conversation shifted from the media to polarization to evolving campaign strategies, the panelists collectively continued to hone in on the need for there to be a greater willingness to consider adversarial perspectives. New initiatives on campus, such as the Community Forum series, have answered this need. Using these spaces, how do we, as a community, foster discussions about some of the most pressing political, social and economic issues of our time?

The Making of a Presidential Candidate assembly felt like a rare instance of addressing politics and current events, as we seldom have such conversations as a community. When we do engage in these discussions inside and outside of class, we frequently dismiss less popular viewpoints because we lack experience conversing with people whose beliefs differ from our own.

Poly teachers should be mindful of when they are establishing these normative beliefs through explicit or implicit support for particular candidates, parties and ideologies. Teachers ought to strive to present themselves as ideologically neutral, teaching students how to think critically in order to formulate our own viewpoints instead of intentionally or unintentionally imparting their beliefs on us or simply assuming we agree with them.

While it may be easy to disregard these concerns because of the Poly community’s overall ideological homogeneity, a lack of intellectual diversity ultimately harms everyone — whether or not they align with conventional thought on our campus. For one, we should not overlook the fact that, albeit a minority, students with differing beliefs do exist on our campus. Brushing them aside makes it more difficult for them to share their ideas. In turn, failing to hear from people with positions across the political spectrum disadvantages students who do fit in with the mainstream beliefs at Poly: we become less likely to consider ideas that differ from our own, less likely to empathize with people with different viewpoints and backgrounds and less likely to break out of our bubble of intellectual conformity — all of which furthers polarization.

We frequently condemn polarization and extremism, yet the onus rests on all of us to build a more inclusive and bipartisan society.

Moving forward, pluralistic political discussion both inside and outside of the classroom is essential. Teachers should guide students in examining sources from a range of viewpoints, taking care to analyze writers’ potential biases. Outside of the classroom, students and faculty alike can encourage dialogue through assemblies, as well as events like the Community Forum series. Leadership groups and club presidents, in particular, can create spaces for conversation, such as the discussion led by the Women’s Service League and FemEd on Friday, Nov. 15. In both class discussions and outside events, facilitators ought to be intentional when wording discussion questions, trying not to have the prompts lead to one particular “answer” but, instead, opening up conversations for exploration and embracing potential disagreement.

Most importantly, it is vital that we continue to have these discussions beyond election season. After all, political engagement must continue after presidential races once every four years, and democracy is strongest when citizens are informed and actively engaged.

Hopefully, Poly can fully realize its mission by promoting diversity in all of its forms.