Grade inflation at Poly: myth or fact?

Over the last eight years, the average end-of-year GPA of Poly juniors has steadily risen from 3.44 to 3.60, based on data from the College Counseling Office.

Grade inflation is hardly unique to Poly. According to a nationwide report released by the ACT, between 2010 and 2021, the average unweighted high school GPA increased from 3.17 to 3.36. Elite universities such as Yale and Harvard have similarly seen the percentage of A’s and A-’s awarded skyrocket to nearly 80% of all awarded grades in recent years, up from 60 to 65% a decade ago.

According to new Upper School Dean of Faculty Harvey Johnson, grade inflation in general stems not from one cause but from many. “As you think of all the stakeholders involved — parents, students, teachers, administrators, colleges — members of these groups have aligned incentives, which, together, push grades higher and compress them,” Johnson said.

English vs. Math: departmental discrepancies

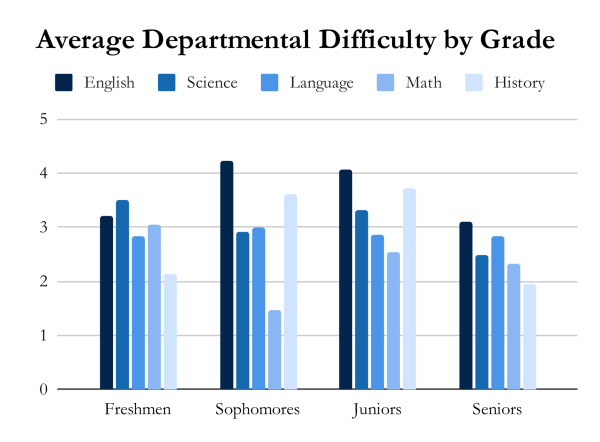

Upper School Director José Melgoza declined to share grade distributions, citing a policy against disclosing data to the public. A Paw Print survey of 135 Upper School students, however, indicated that not all academic departments at Poly have experienced grade inflation to the same degree.

When asked to rank their English, science, history, math and world language classes this year from 1 (easiest to obtain an A) to 5 (hardest to obtain an A), 44% gave their English class a 5, compared to 17% for science, 14% for world language, 13% for history class and 8% for math. On the other end of the spectrum, 33% of respondents rated their math class a 1, compared to 25% for history, 15% for world language, 10% for science and 8% for English.

The perceived difficulty of a class didn’t necessarily correlate with whether the student considered themselves stronger in STEM or humanities, nor with how much work they invested in the class.

“I’ve always studied and worked hard for my English classes but struggled to get an A,” said a junior. “However, I never studied for math quizzes or tests, and I’m always at a comfortable A.”

Several students attributed the difficulty of English and history classes to the qualitative nature of assessments.

“Humanities classes are inherently more subjective because there isn’t necessarily a correct or incorrect answer depending on how you defend your arguments,” said a senior.

As English Department Chair Marge Kenny explained, “In writing an English paper, there are so many different skills involved that I know can be frustrating for students who want to have all the right answers at once, but the process is so much more nuanced than that.”

Multiple students pointed out that higher grades in STEM courses may also result from extra credit, which can increase grades by 20% or more. In AP Calculus, students can boost their test scores by doing additional problems, while in AP Physics, students can accumulate bonus points through optional assignments.

Math Department Chair Jack Prater defended extra credit as an incentive for students to push the boundaries of their knowledge. “It’s hard for them to be willing to take that step on their own. But when they’re being assessed, they’re more willing to take that chance, and they’re more adventurous if the penalty for not being successful isn’t as severe,” he said.

“Tough graders”: grading within departments

Some students felt that the more significant differences in grading were not between departments but between different teachers within each department.

“I don’t think that one department is generally more rigorous than another, but I do believe that specific teachers within a department are much harsher when grading versus the other teachers,” said a senior.

“Everyone who has taken an English class at Poly knows that some teachers’ classes are a lot harder than other teachers’, even though those different teachers should teach the exact same English class,” echoed a junior, who noted a similar pattern in the history department.

Another junior agreed: “I couldn’t get a single A, not even an A-, in English my whole freshman year, but last year I ended English with a 96%, and this year I have a 93%. I know I have improved in English, but I don’t attribute it to the teacher who wouldn’t give me a good grade.”

Some students speculated that newer faculty members tend to take a different approach to grading than longer-tenured faculty. “Looking back at all the teachers I’ve had, I definitely see a pattern between easier teachers being newer and younger ones,” said a senior.

In his short time at Poly, Johnson has begun applying mathematical tools to analyze whether distributions across sections of the same class vary between teachers.

“When I say the letter A or B or C, lots of different constituents make meaning of those letters in different ways,” he said. “One of my jobs is to help groups of people make meaning of those grades so that constituents understand each other — students and teachers, teachers and teachers, and members across academic departments.”

Kenny indicated that these efforts have been paying off. “We have really made a concerted effort to work more closely on grade-level teams to ensure that there’s parity between classes,” Kenny stated. “You shouldn’t feel like your grade is going to be determined by whom you have as a teacher. A grade should be a reflection of the skills that you are demonstrating and the expectations of the course.”

As grades rise, what about academic rigor?

The rise of GPAs at Poly has been accompanied by lessening student workloads. Due to the implementation of the current block day schedule in 2016 and the imposition of homework limits shortly thereafter, teachers have significantly reduced the amount of material they cover.

“When we went to this new schedule, we had to really decide where we were going to trim. So we reshaped the classes, but the endpoints remained the same,” said Prater, who assigns half the number of practice problems as he previously did.

Upper School history teacher Rick Caragher — who has cut back on reading by 40 or 50% over the last ten years — said these circumstances and emerging conversations around teaching have directed him to place less emphasis on memorization and more on depth of thinking. “As I teach world history, there’s so much to cover that it’s far more effective to dive deeply into some subjects than to try to cover everything,” he noted.

Other teachers have struggled to balance workload and student well-being while maintaining high rigor. “The school has realized that the kind of stress that was being generated in the old days was not good for students in the long run,” said one teacher who wished to remain anonymous. “But you still have teachers who are trying to teach to the level of rigor that used to exist — in an environment that’s designed to have that not be the case.”

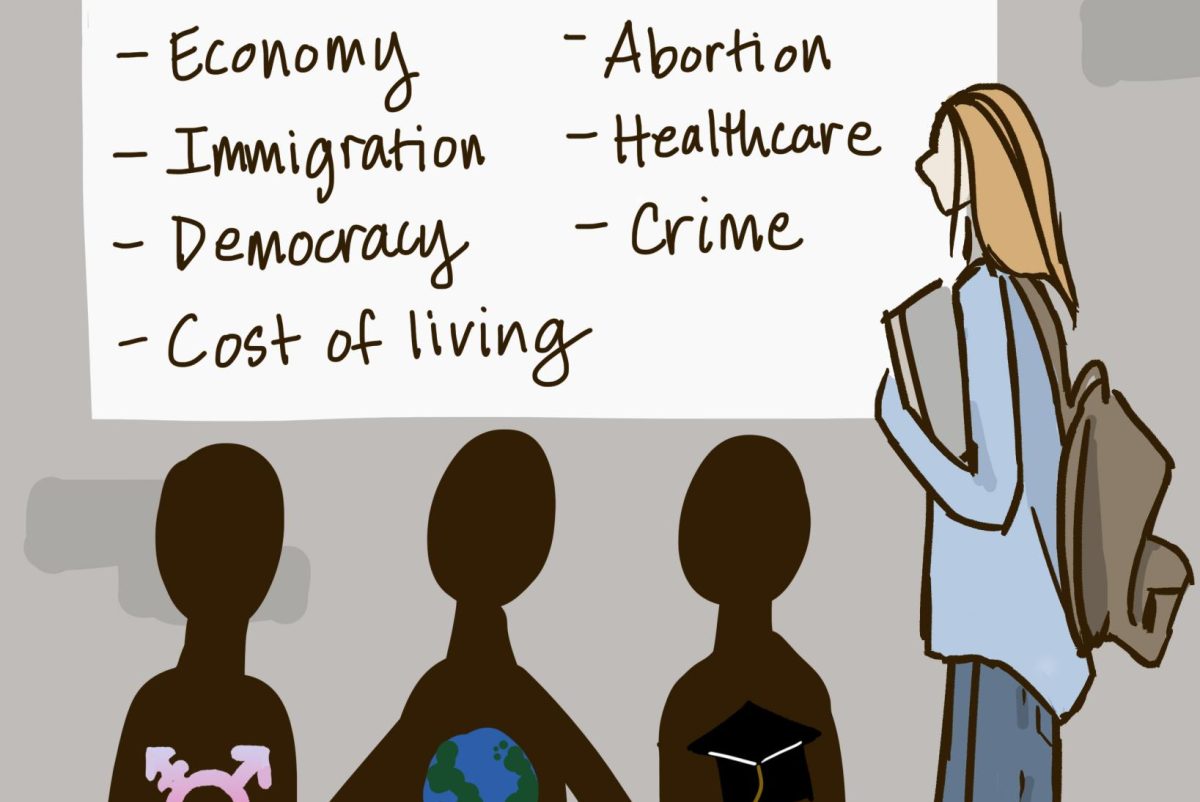

A new era: administrative and student priorities

Poly’s evolving academic standards can be traced to increasingly demanding extracurriculars and shifting administrative priorities. “When our most recent head came in, he was known for being very attuned to students and student life,” said Upper School physics teacher Craig Fletcher, who joined Poly in 1978. “We have migrated away from extreme academics to a situation in which we have academics, and if you want to take to the hilt and stretch yourself out, you can do that — but if you don’t want to do that, you can get through the school just fine.”

A teacher who wished to remain anonymous suggested that the expansion of the student body over the past few decades has affected Poly’s academic environment: “It’s very difficult to find that level of intellectual horsepower in really large numbers. We still have bright kids, but we also have kids that would have had a lot of trouble 30 years ago dealing with what we were asking kids to do then.

Upper School physics and computer science teacher Richard White, who has been at Poly since 2004, pointed to the school’s changing admissions philosophy to explain how academic expectations have evolved.

“Poly has done a great job of trying to diversify the school in lots of different ways, including bringing in students who haven’t had some of the academic background or benefits that students in the past have had,” White said. “Bringing in people whose interests are less academic, maybe, and more athletic or more artistic — that’s a super good thing for a school to have. But that necessarily means if you have fewer ‘academics,’ you’re going to have a wider range of abilities academically.”

While her grade distributions have not fluctuated significantly, Kenny acknowledged that certain skill levels of students in ninth-grade English have changed over the last decade.

“Many students don’t read as much as they used to read,” she said, citing the impacts of ubiquitous technology and the attention economy. “There’s been some natural adjustment in grading to meet students where they are developmentally.”

The Math Department has similarly seen a broad spectrum of mathematical backgrounds, with averages in the accelerated math track typically skewing higher than averages in the honors track. Nevertheless, both Prater and White agreed that the academic achievement of Poly students continues to be compressed to the high end.

“At a small place like this, where we’re so invested in student outcomes, our grade distribution isn’t that normal distribution around a C,” said Prater. “We have higher expectations, we strive for our kids to excel, and we do everything in our power to help them excel. And the fact that our grades tend to skew more towards good and excellent is the whole purpose of what we’re trying to achieve.”

Grades in context: is there a cost to more As?

Regardless of whether academic expectations or GPAs have shifted over the years, these changes do not appear to have impacted college acceptance rates.

“In recent years we’ve been doing very well, and that to us is a sign that our grades are respected and that outside institutions, colleges in particular, understand that our students are as advertised,” said Melgoza.

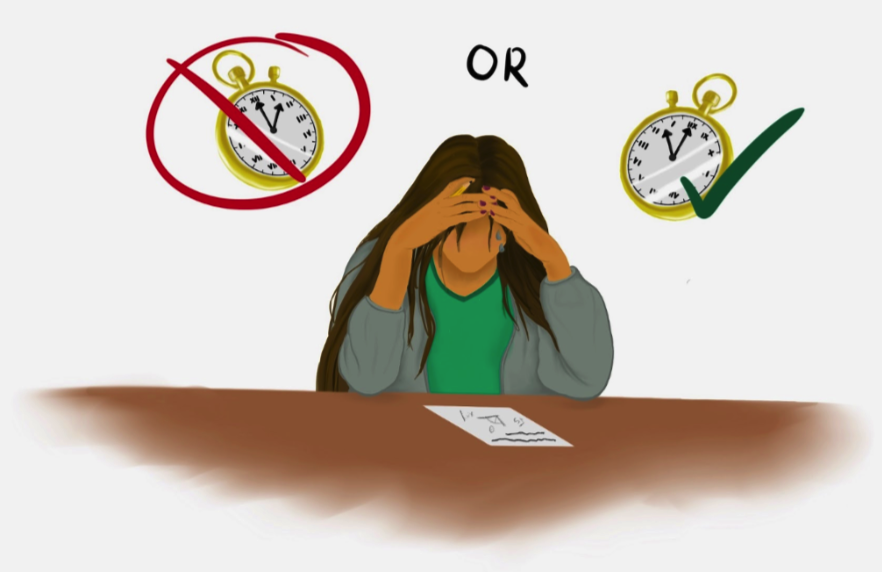

Easier attainment of A’s, however, demotivates some students from striving for academic excellence. In a Paw Print survey, 43% of Upper School students agreed that they learn more if they have to work hard for a “good grade,” while 22% disagreed.

At the same time, teachers expressed concern that fixation on grades distracts from learning, especially when students think of A’s as the norm.

“The more grades go up, the more people are getting higher grades. If you’re not part of that, that puts more stress on you,” said Caragher. “Having the focus on grades distorts our ability to learn, and it also can also adversely affect those who are struggling.”

Kenny shared, “I think most English teachers would like to emphasize their narrative feedback to their students about how to improve rather than communicate student progress through letter or numerical grades. For better or for worse, grades are the currency that we’re tied to right now.”

Conway • Feb 20, 2024 at 1:53 pm

This is the best article I’ve ever seen!! It shows incredible things I never would’ve thought about. Thanks for this wonderful article. So many great quotes, great writing, and great things. Definitely a deserved feature and an exclusive article from the best of the best.

#ReadThisArticle

#AmazingArticle

#TopLiterature

So many interesting facts, thanks again for the great writing.