Over the last decade, the private tutoring industry has boomed — and with increased demand has come exorbitant prices. At companies such as Compass and Advantage Testing, tutors charge between $170 and $715 per hour.

But these prices have not deterred Poly clientele.

In a Paw Print survey of 82 Upper School students, 46% said they had worked with a private tutor during high school. Of the students who received academic tutoring, 63% have been tutored in math, 50% in science, 37% in English, 10% in World Language and none in History. Of surveyed juniors and seniors, 48% have worked with tutors to prepare for standardized tests such as the SAT and ACT.

These figures diverge dramatically with socioeconomic status. At Poly, only 18% of students surveyed on financial aid have ever been tutored, compared to 54% of students not on financial aid.

Why use tutors?

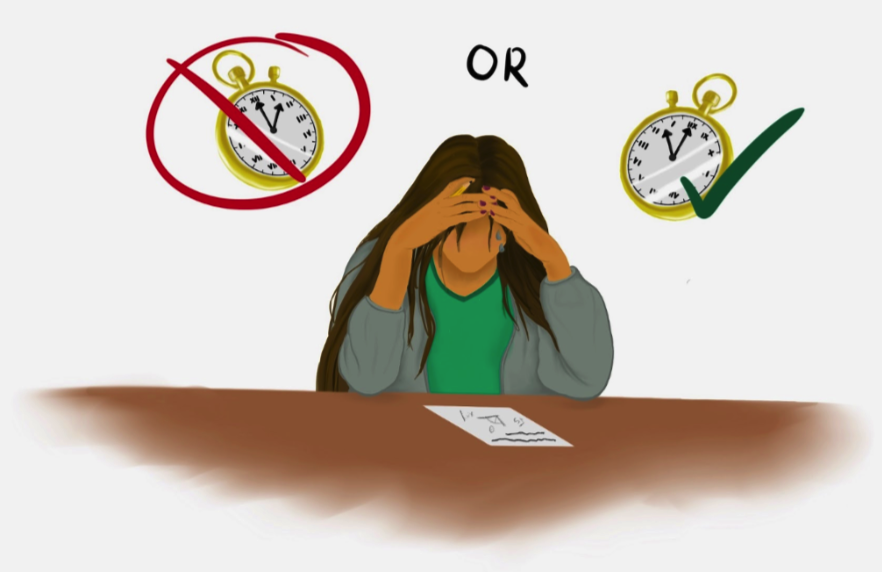

Most students with private tutors feel they benefit from the flexibility of learning at a pace tailored to their individual learning styles.

“Tutoring helps clear your understanding in a one-on-one setting in which you are not afraid to ask questions or are not limited by time,” stated a sophomore who receives math tutoring.

Some students said tutoring eased their transition to Poly. “The teachers at the Upper School know what you’ve learned in the [Poly] middle school, so they know how to explain it to you in a way that makes sense to you,” said senior Maddie Hays, who joined Poly in 9th grade. “But none of the teachers here understand the way my eighth-grade math teacher taught me algebra, and [tutors] try and put it in terms you understand.”

Tutors can also be helpful for students with learning accommodations. Junior Catie Sabbag, who has ADHD, works with an educational therapist to write more cohesive English papers. “I think Poly, especially in the English Department, expects you to already have a certain level of expertise, and [my educational therapist] breaks it down a little bit more,” she explained.

Other students turn to tutors out of frustration with their teachers.

“My teacher did not know the subject matter and was unhelpful during Extra Help,” said a senior who received science tutoring. “The extra help from tutoring was minimal and did not make up for the hours of time lost during the week to a class in which the concepts were presented incorrectly or in a confusing way.”

While students felt tutoring helped them better understand the material, the end goal for many was a higher grade or AP score. “My teacher grades writing assignments excessively harshly with new reasons the work is mediocre each time,” said a freshman who receives English tutoring. “My tutor reassures me I can close in on the wide grade gap to an A.”

Teachers versus tutors

Teachers acknowledged that tutoring could be beneficial to certain students but expressed reservations about its usage.

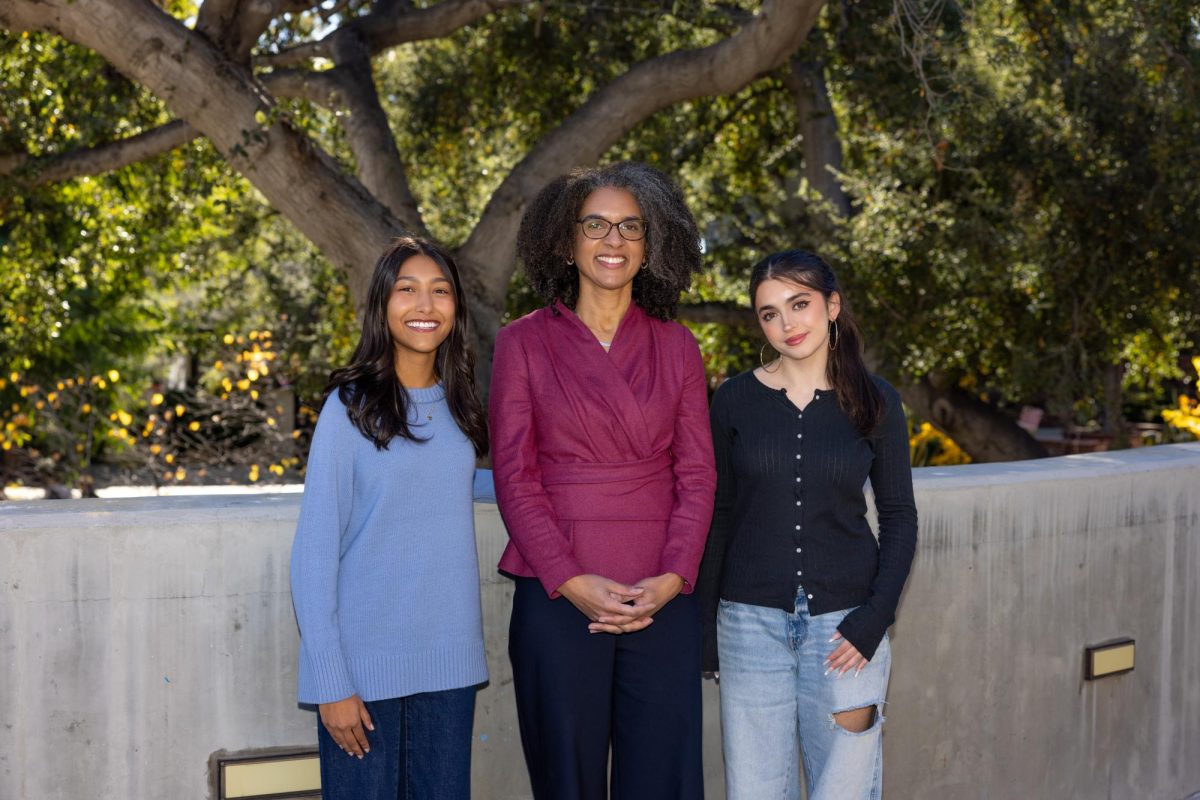

“Usually I think the best person to work with you is going to be one of us because we know what the program is. If a tutor knows the school or is in contact with the teacher, they’re going to be more effective,” said Upper School English teacher Laura Marion.

The Upper School English Department tutoring policy states, “Tutors must communicate with the student’s dean and teacher prior to helping a student.” In actuality, however, only a fifth of surveyed students notified any teacher about receiving academic tutoring.

Upper School chemistry teacher Gillian Bush — who runs an outside tutoring business and has tutored Poly students not in her classes for decades — emphasized that tutors can support but should not replace teachers.

“Most teachers have at least a small number of students for whom they would admit a tutor could be helpful,” Bush noted. “If what they need is someone’s undivided attention for an hour or several hours, then really that’s what a tutor’s for. If they have a quick question or they miss class and want a 20-minute primer on what happened, the teacher is the absolute right person to go to.”

Upper School Director José Melgoza warned about the long-term costs of using tutors who do students’ work for them — a violation of Poly’s Honor Code. “You might think that it’s going to give you that little bump up,” he said, “but you’re paying a price for that bump up — and that’s a price in terms of trust and in terms of how the teacher views you as a person with integrity.”

Stigma and secrecy

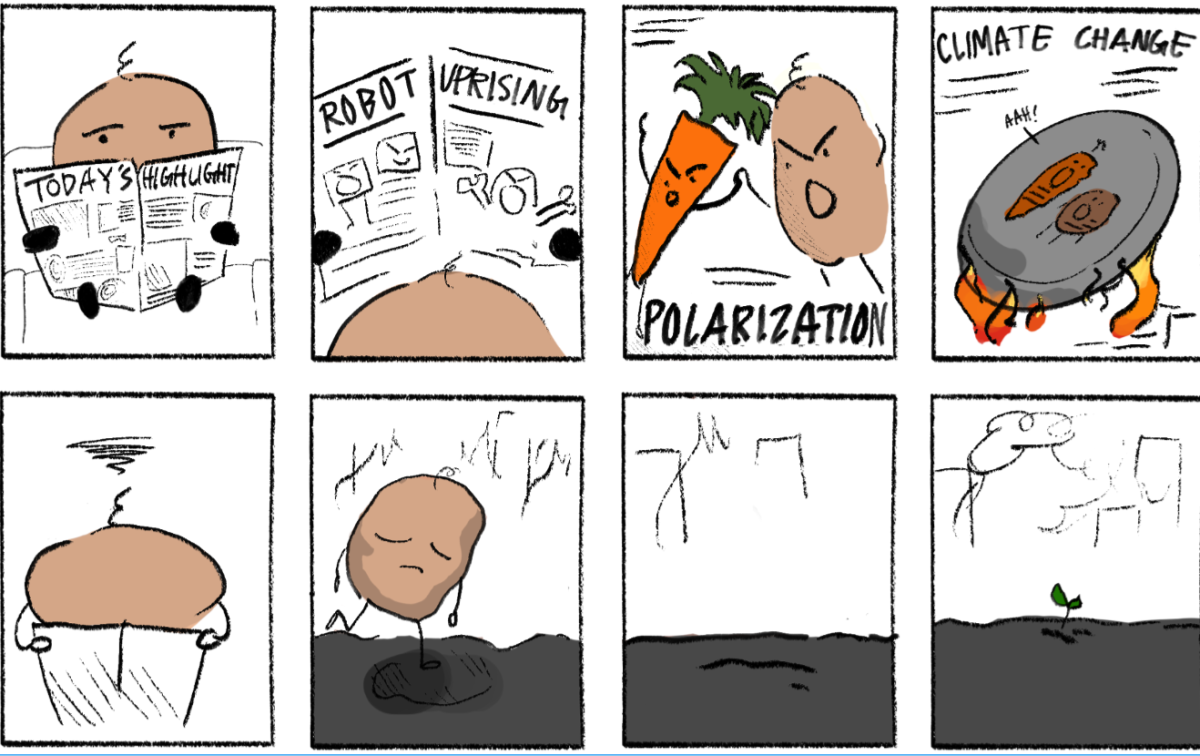

Many students said that Poly’s culture makes open discussion about tutors seem taboo.

“I think there’s this culture at Poly where the expectation is that everyone is smart enough to handle every class,” one senior explained. “People always say, ‘I didn’t take this hard class because I didn’t want the workload.’ If you’re struggling, it’s because you’re lazy. But sometimes you’re struggling because the class is just not designed in a way that meshes with the way that you learn, or there isn’t enough support.”

Hays added that being tutored should not carry stigma. “People associate tutoring with remedial efforts and needing to rise to meet the rigor of the class, but I think it can also be used to go above the rigor of the class. Once I got over that mental block, I started using tutors for any subject that I struggled with,” she said.

An uneven playing field

The benefits of one-on-one help raise equity concerns for students who cannot afford to shell out hundreds or thousands of dollars on tutoring. Although Poly offers Extra Help time, the Writers’ Center, peer tutoring and a learning specialist, students said these resources are not necessarily equivalent to private tutoring.

“Although Poly tries their best to make every Poly student’s experience equitable, somewhere where their oversight fails is students’ lack of financial access to tutoring resources,” commented a junior who receives financial aid.

According to Marion, teachers strive to address these concerns in their grading, and the English Department tutoring policy specifies that “tutors may not help with anything assigned or graded.”

“Part of our philosophy is to try to make it so tutoring doesn’t have any impact,” Marion said. “For the kids that get tutoring, it would only help them get better in English but not help them get better grades on assignments.”

Melgoza acknowledged the inequities that private tutoring creates but pointed to Extra Help time as one way Poly seeks to level the playing field. “It’s impossible to ever have a 100% equal playing field, but I think that in terms of what other comparable schools have done, the fact that we have committed time in our schedule to make those teachers available is pretty unique.”

The Extra Help program comes on top of already small Upper School classes averaging 15 students — half of the average class size in Los Angeles Unified School District public high schools. Notwithstanding these privileges, there does not appear to be any slowdown in the number of Poly families jumping on the tutoring train.