At a high school as prestigious as Poly, eager class participation is far from an aberration; however, we don’t always recognize which voices dominate the intellectual sphere. In academic environments, particularly high school and college, male students feel a greater license to speak up and share their opinions than their female counterparts.

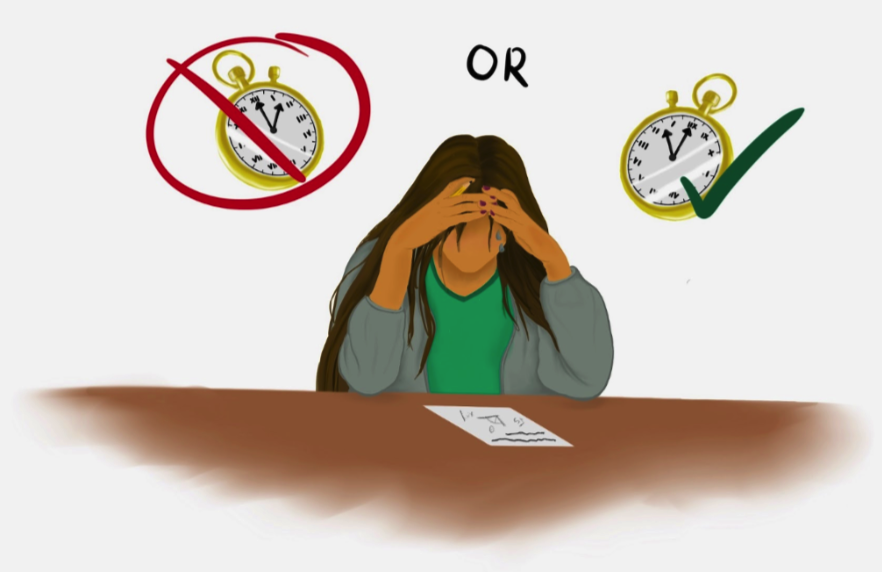

This dynamic can be a self-fulfilling prophecy: as male voices dominate classroom participation because they’ve been socially conditioned to do so, they perpetuate a territorial paradigm wherein female students feel as if they are encroaching when they enter academic conversations. An article discussing gender equity in the classroom from the Duke Chronicle names this psychological phenomenon the stereotype threat. The threat dictates that a woman’s academic performance and participation are likely to decrease when she is in a situation that activates any negative stereotypes concerning her intellectual capabilities.

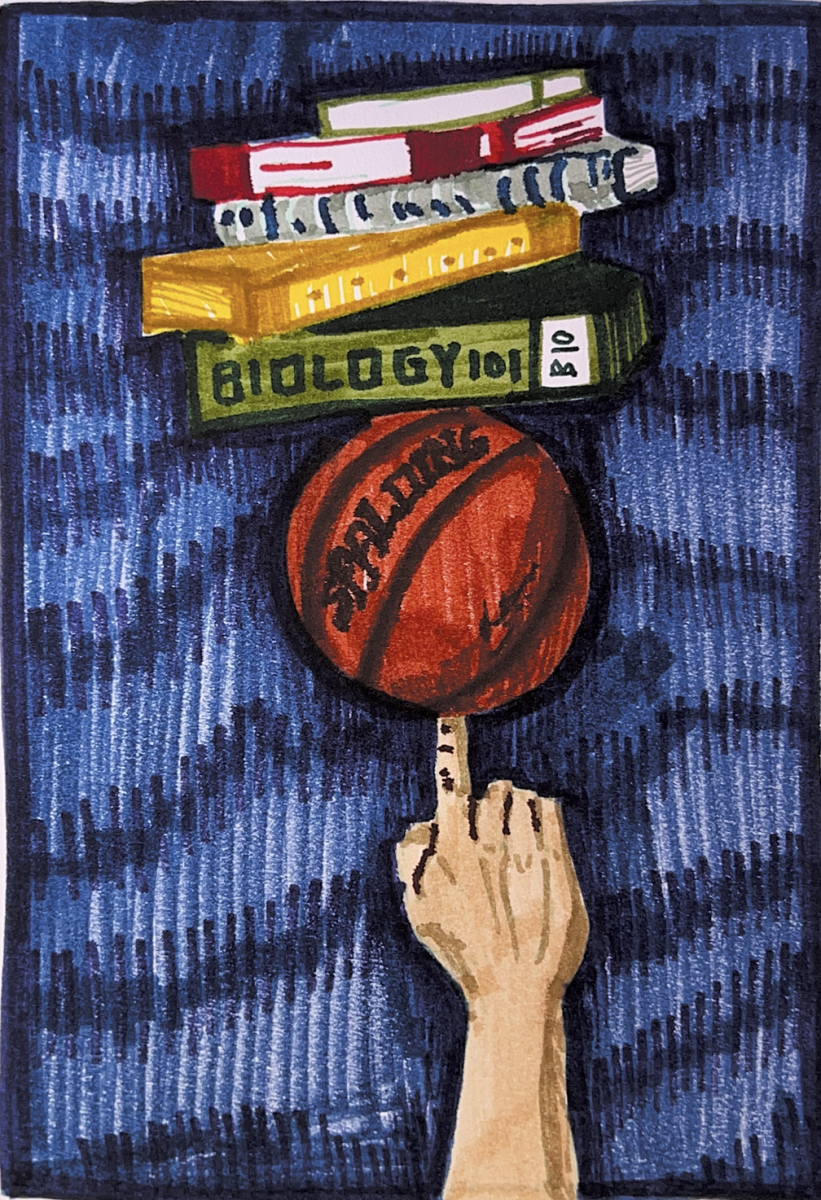

For example, if a woman enrolls in an advanced STEM course knowing that there are fewer women represented in the field, she may be less comfortable participating in discussions. Additionally, she may feel compelled to dim down her ambition and appear as amiable as possible, according to a survey conducted by the Harvard Business Review that cites about half of female scientists (53.0%) reporting backlash “for displaying stereotypically ‘masculine’ behaviors like speaking their minds directly or being decisive.”

Aside from the specific challenges women must navigate in the STEM field, girls are indoctrinated with gendered models of learning throughout their educational careers. Female students are often encouraged to be more soft-spoken while boys are implored to speak up, and, as outlined in a 2015 Time Magazine article titled “All Teachers Should Be Trained To Overcome Their Hidden Biases,” which explores the ways implicit and stereotypical ideas about gender govern classroom dynamics, teachers spend up to two-thirds of their time talking to exclusively male students.

The perpetuation of systemic discrepancies in the classroom leads female-identifying students to believe that their voices are dispensable or, worse, that their ambition detracts from their femininity.

Dr. Maria do Mar Pereira, a sociologist from the University of Warwick, explains, “Young people try to adapt their behaviors according to… pressures to fit into society. One of these pressures is that young men must be more dominant – cleverer, stronger, taller, funnier – and that being in a relationship with a woman who is more intelligent will undermine their masculinity.” Female students are forced to navigate unforgiving double standards, fearing ostracism and social backlash for speaking over their male classmates, even if they were talked over to begin with.

While progressive private schools may fancy themselves free of such harmful behaviors, we cannot pretend that these socially conditioned differences do not manifest in our very own classrooms. As a female-identifying student who has been at Poly since 6th grade, I’ve suffered my fair share of rolled eyes at the sight of my raised hand, as well as comments about being abrasive, overeager, or bossy from my male classmates. As such, I was led to believe that likeability and academic zeal were mutually exclusive. Even though gender is not the only factor when it comes to whose voices are heard in the classroom and beyond, it is nonetheless worth examining as students and future leaders because I, for one, hope to avoid years more of backhanded comments.

Sophomore Kelly Zhang, a female student at Poly, shares a similar experience in one of her STEM classes, echoing behavioral trends across grades and classes: “Even when I raise my hand, it feels like I can’t share my ideas because the boys in my class often speak over me. This makes it seem like I’m really quiet, even though I have a lot of ideas. I don’t want to speak over them and come across as rude, so the class becomes less engaging and enjoyable for me.”

A standard method of counteracting these issues is to revert to single-sex classrooms or schools, but this would fail to acknowledge the mutual intellectual growth that emerges from coed spaces, such as exposure to a wider range of backgrounds and experiences. A better solution would be to first acknowledge the structural behaviors that create inequitable spaces. An example of this at Poly that the school could model more widely is the DEI discussions held in 9th-grade Integrated Science.

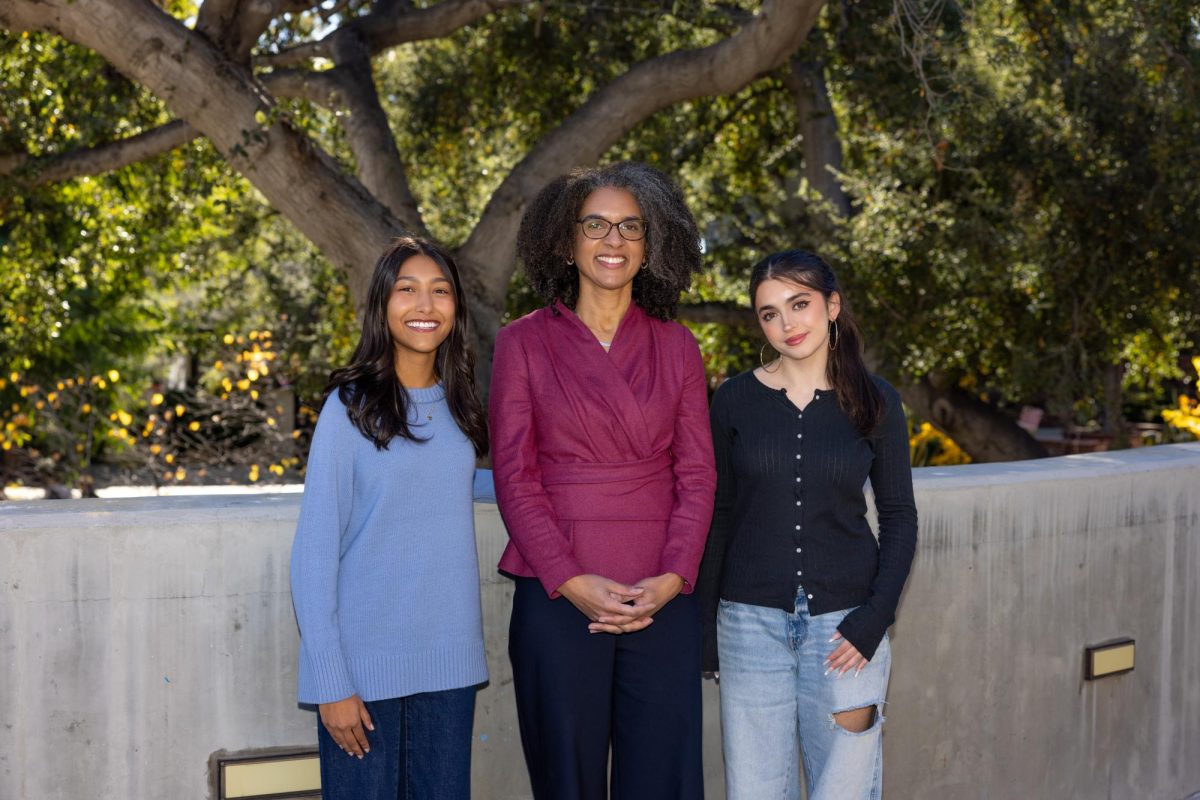

The Integrated Science teachers host class discussions throughout the academic year, examining different aspects of identity and their representation — or lack thereof — in the STEM field. Poly science teacher Rachel Dunham, who first introduced these discussions to the curriculum, encourages dialogue about gender disparities, saying, “The first step is acknowledging that it’s a thing.”

When asked about the efficacy of the discussions, Dunham noted, “I definitely got feedback from students on their student feedback forms…. I had lots of students sharing that ‘I’m really pleased that we’re talking about this,’ or, ‘I never thought about x, y, z.’”

As young adults living in the 21st century, many of us are inclined to discount yet another DEI conversation. And while you might view this article as another instance of beating a dead horse, it’s important to recognize our biases and the potential harm they can incite. Through conversations such as these, we are less likely to succumb to our preconceived notions, and, even though we cannot fully combat years of social conditioning in a few hour-long class periods, we can more actively try to rectify structurally perpetuated disparities.