My love of books began before I could even read them.

My dad read to me when I was younger––when I was still finding my footing in the phonetics and sound, intrigued by stories but unable to piece their letters together. We worked through the entire Harry Potter series before I finished kindergarten, a voraciousness I carried throughout my time in school, filling my shelves with literary classics and Googling every new word I discovered.

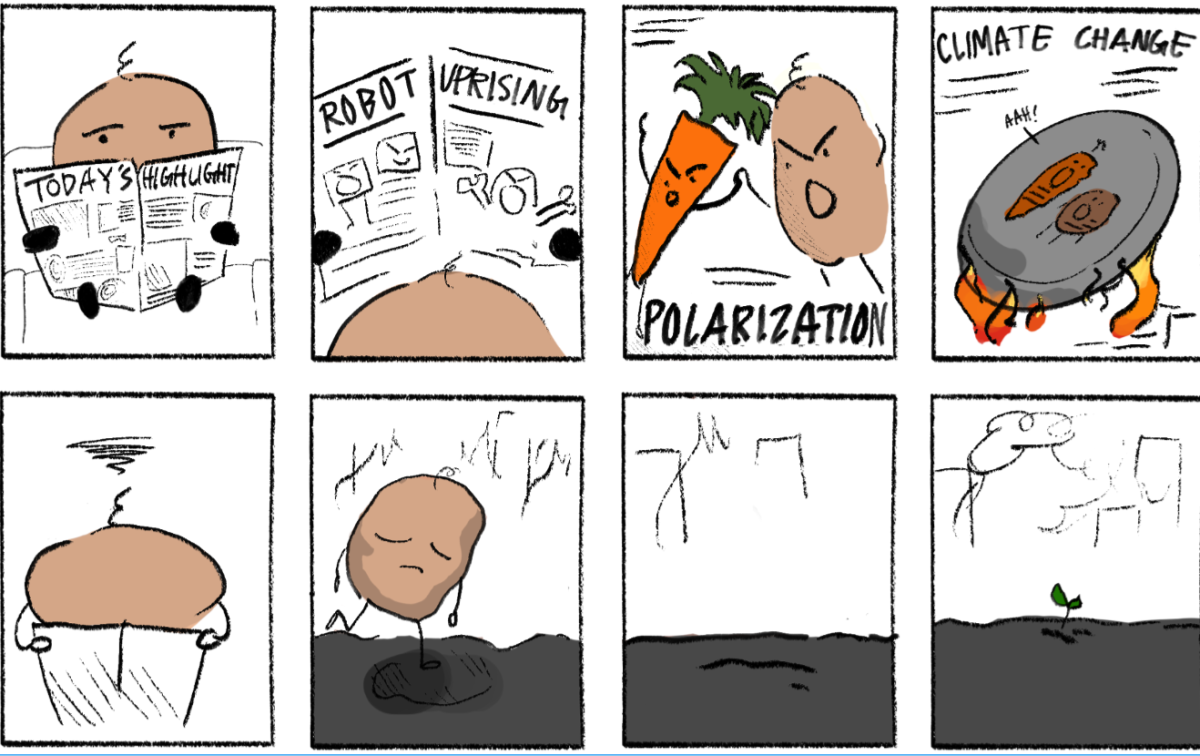

Today, however, I see fewer and fewer people excited by the act of reading. Many feel that their time could be better spent on other pursuits. Or, they find the prospect of reading boring, a “waste” of free time. In short, an increasing number of people view reading as a chore.

A recent National Endowment for the Arts survey found that 51.5% of Americans didn’t read a single book in 2022. In the following year, the American Psychological Association announced that less than 20% of U.S. teens report reading a book, magazine or newspaper daily for pleasure, while more than 80 percent say they use social media every day.

This trend has stark consequences: per the Associated Press, thirty-three percent of eighth graders scored “below basic” on reading skills, meaning they were unable to determine the main idea of a text or identify differing sides of an argument. This was the worst result in the exam’s 32-year history.

The conclusion is clear: our society is becoming apathetic to literature.

When students at Poly think of reading, we think of the reading we do in school––pages of detailed annotations, anxieties about pop quizzes looming in our minds. However, reading comprehension is more than an academic skill. In a world where information is abundant and often overwhelming, the ability to analyze and interpret text is indispensable.

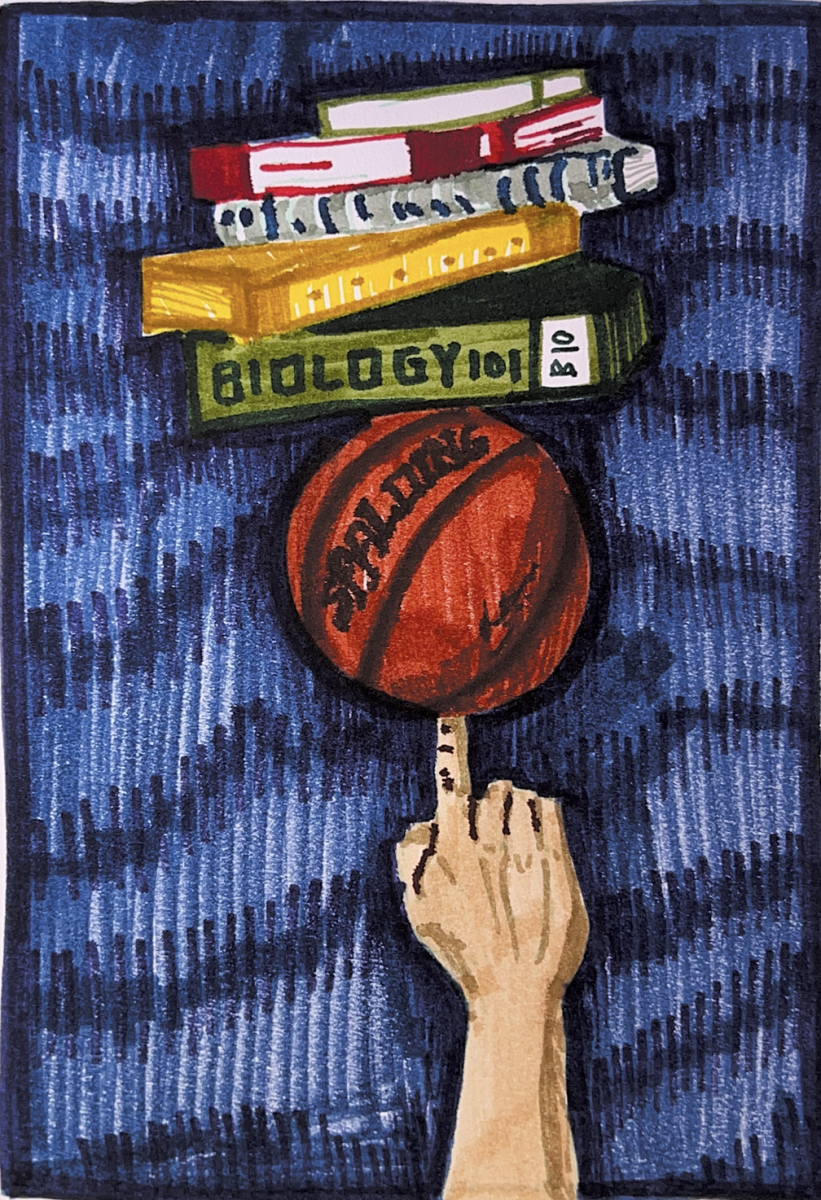

As the National Assessment of Educational Progress has observed, students with strong reading skills are better equipped to synthesize information and solve complex problems. Reading can be strategic, exposing us to SAT vocabulary and dispensing useful information, but its true value lies in its humanity––in a book’s emotional core.

The first time I read Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, I knew I had found my favorite book. I gravitated towards the page because his writing refracted fragments of my life––forgotten aches and embarrassments––through metaphor and similes, exhuming the scars of old injuries with poetic prose. I finished the novel in a week, exiling my homework to the edge of my desk as I gorged on line after line, chapter after chapter.

While I had always been a reader, I suddenly understood why.

Vuong writes, “To be gorgeous, you must first be seen, but to be seen allows you to be hunted.” Good writing does this—it sees us. There is something unnerving about reading a passage and feeling, in your gut, the sharp recognition of your own experiences laid bare. And yet, there is power in that exposure. It can be profoundly reassuring knowing those feelings simmering and festering in the corners of your mind are no longer your burden, that they are shared by an entire group of people.

After all, literature is a form of communion—a way for writers and readers to cross physical borders and convene in thought, to share in the rawness of being alive.

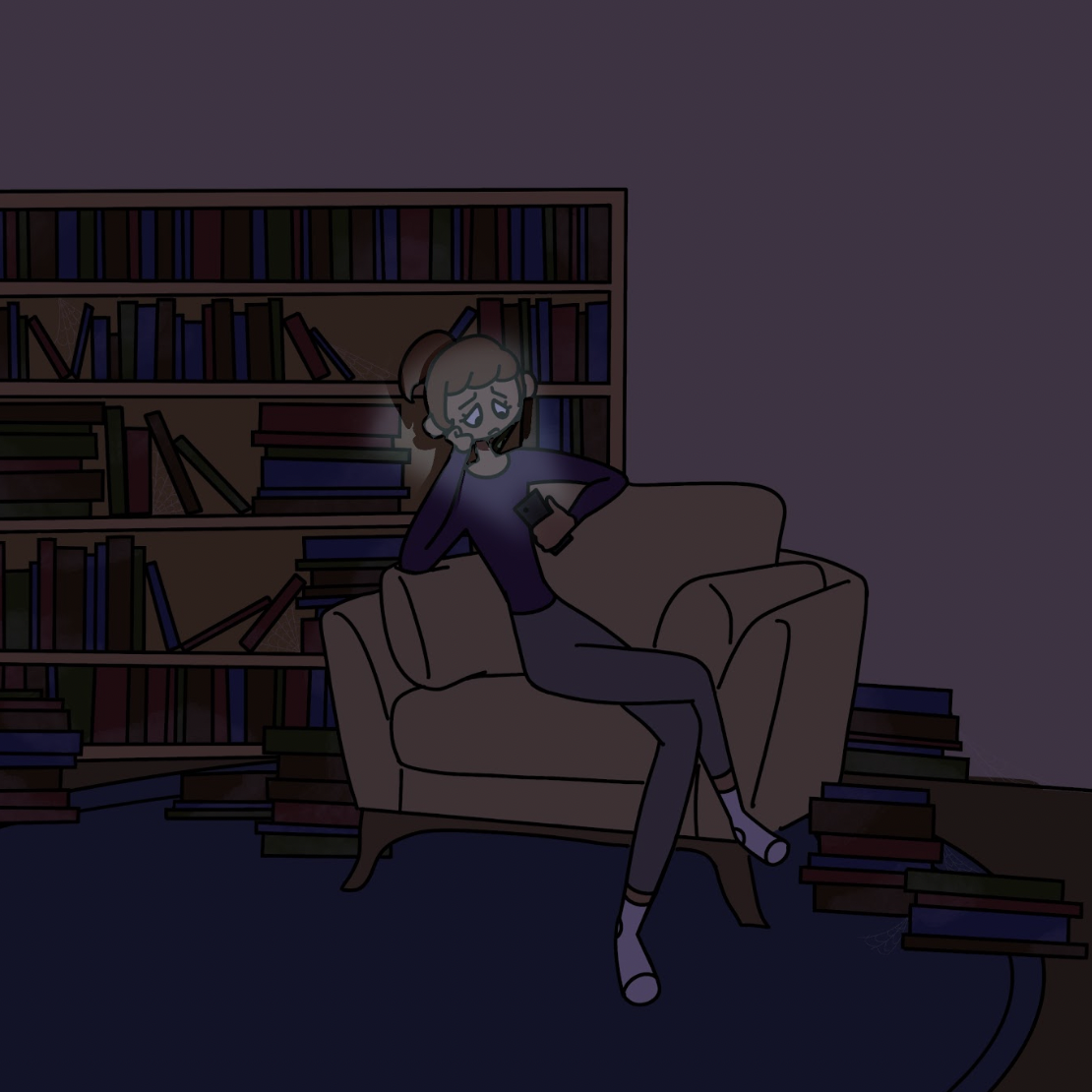

But while several books hold a mirror to our lives, reading can also act as a refuge from reality. As junior Catherine McFarlane noted, “I love reading because it allows you to escape into a new world. It feels very freeing in that way.” In times of stress or uncertainty, a book becomes a sanctuary—a portal to far-off realms, our concerns and anxieties falling between the pages. Unlike TV shows, where our thoughts can easily wander to the nearest worry, reading demands full engagement with the storyline; we are grounded in the plot, shielded from external concerns.

There’s a reason English teachers and writing instructors across the globe preach reading as a prerequisite to writing.

“Reading also provides me with so much inspiration for my own writing, both in and out of English class,” McFarlane added.

“Reading exposes us to other styles, other voices, other forms, and other genres of writing. Importantly, it exposes us to writing that’s better than our own and helps us to improve,” says author and writing teacher Roz Morris. Aspiring writers must dissect poems and novels, picking apart sentences and stanzas until they can take the fundamentals of language and birth something of their own. Moreover, well-written books are inspiring, as they remind us that we, too, can transform our lives into something beautiful––that we can immortalize ourselves on the page.

As high school English teacher Tim Donahue wrote in a New York Times guest essay, “We cannot let reading become another bygone practice.” He adds, “ The comprehension of literature, on which the study of English is based, is rooted in the pleasure of reading. Sometimes there will be a beam of light that falls on a room of students collectively leaning into a story, with only the scuffing sounds of pages, and it’s as though all our heartbeats have slowed. But we have introduced so many antagonists to scrape against this stillness that reading seems to be impractical.

Reading is fundamental to what it means to be human––to think critically and process the world around us––and it’s time to rediscover its power.