On Nov. 6, former President Donald Trump won the 2024 presidential election by a sweeping amount against Vice President Kamala Harris, amassing 76 million votes to Harris’ 73 million. He will become the 47th president of the United States, continuing to share one common characteristic with all previous presidents: being a man. Indeed, in the 248 years of American history, there has not been a single female president.

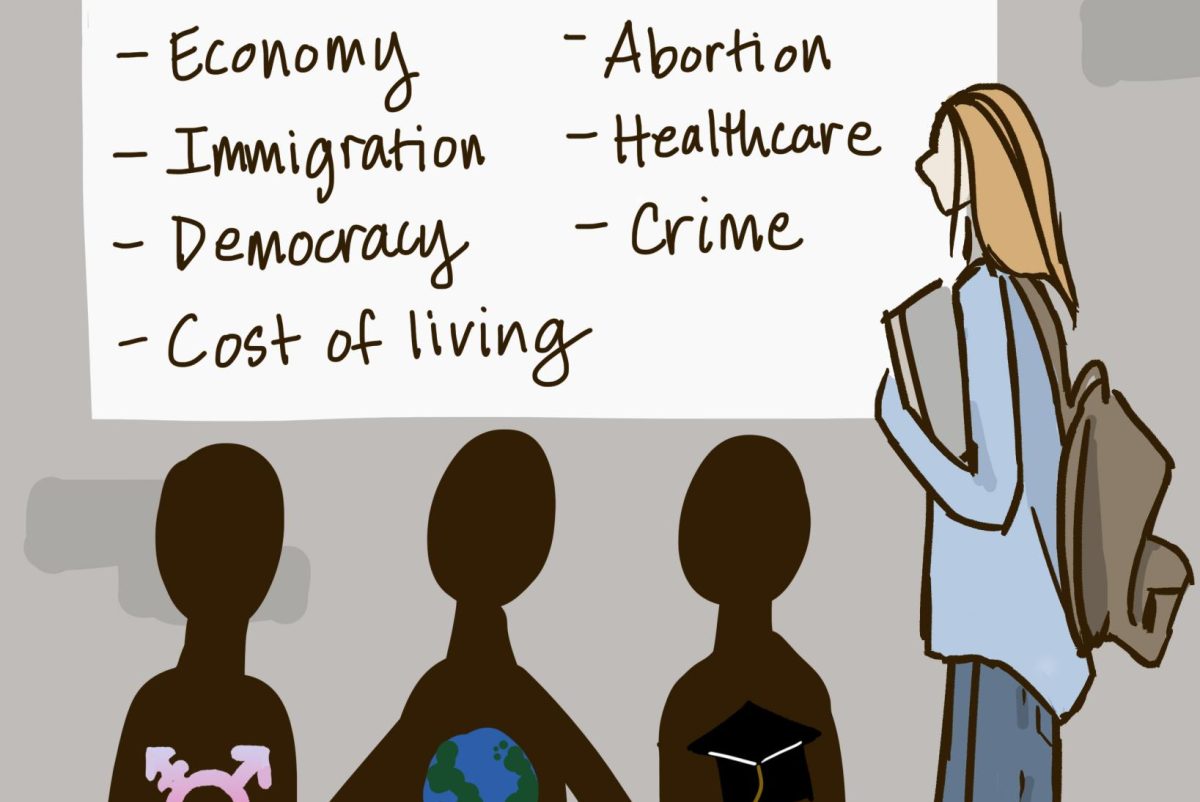

Director of Tufts University’s Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg found that this year, “It’s not the case that young people overwhelmingly supported Democrats.” After watching states turn red or blue on election night, many of us were left with one question: why would 47% of voters aged 18 to 29 vote for Trump over Harris?

While there are a number of factors that led many voters to cast their ballots for Trump, leading to his victory, this result can be largely attributed to the conviction that men are “natural leaders” — an idea implanted in much of the world’s history. For almost two-and-a-half centuries, men have predominantly occupied leadership roles in the United States. Society has cultivated a long-standing bias that men are inherently suited for leadership during this time. Thus, it is difficult for women such as Harris to break through these preconceived notions. The “glass ceiling” limits women’s opportunities to advance in leadership positions, particularly in politics. When people see fewer women in higher political leadership, many augment their bias that women cannot be in positions of power. Thus, despite women’s qualifications and capabilities, societal expectations hold these females back and prevent them from fulfilling the same level of influence and recognition as their male counterparts.

Furthermore, the U.S. is the most individualistic country in the world. Yet, this image is typically associated with men because they were originally seen as the “head of the household.”

According to U.S. History teacher Avi McClelland-Cohen, “Women have been excluded from all aspects of public life historically. Part of this reason is that American culture is also driven by militarism, which is associated with a more masculine image.”

These American values directly translate to elections: when citizens elect the president, they consciously or unconsciously follow the construct that men can lead the U.S. more toward the values of superiority and individuality.

Moreover, despite significant strides toward gender equality, such as the balancing of wages and the number of female senators, representatives, and governors reaching a record high in the past four years, women are still underrepresented in the political climate. Beyond presidencies alone, all female leaders in the U.S. still face pervasive stereotypes and double standards that hinder the normalized acceptance of women in political roles.

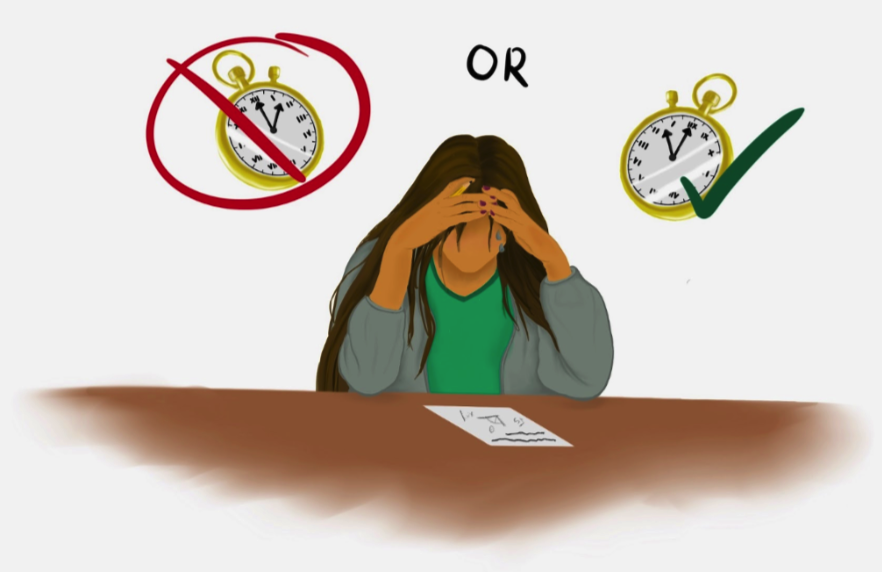

Assertive women are often mislabeled as aggressive, while those who display empathy are dismissed as weak. According to an article from Harvard Business Review, assertive behavior in women is perceived as aggressive. This double standard creates an environment in which women fail to be considered capable leaders. Women, in general, are expected to balance strength with compassion; thus, they confront an undue burden of thriving in the same leadership roles as men.

Society also often compels women to tone themselves down, as an over-the-top woman can usually be perceived as dramatic or a “pick-me”—someone who, in an attempt to stand out, exaggerates her behavior to gain approval. On the other hand, men can take up an entire room and still simply be perceived as funny.

Women also confront a phenomenon that will place them in leadership roles during times of crisis or downturn, setting them up for potential failure: the glass cliff. When women succeed in these precarious positions, their accomplishments are typically undervalued or attributed to luck rather than skill or hard work, making it harder for individuals to view women as viable candidates for higher office.

Even once women attain leadership roles, any missteps reinforce the stereotype that women do not have the qualities to lead. Thus, this inherent skepticism of women creates a cycle in which men repeatedly become leaders instead of women.

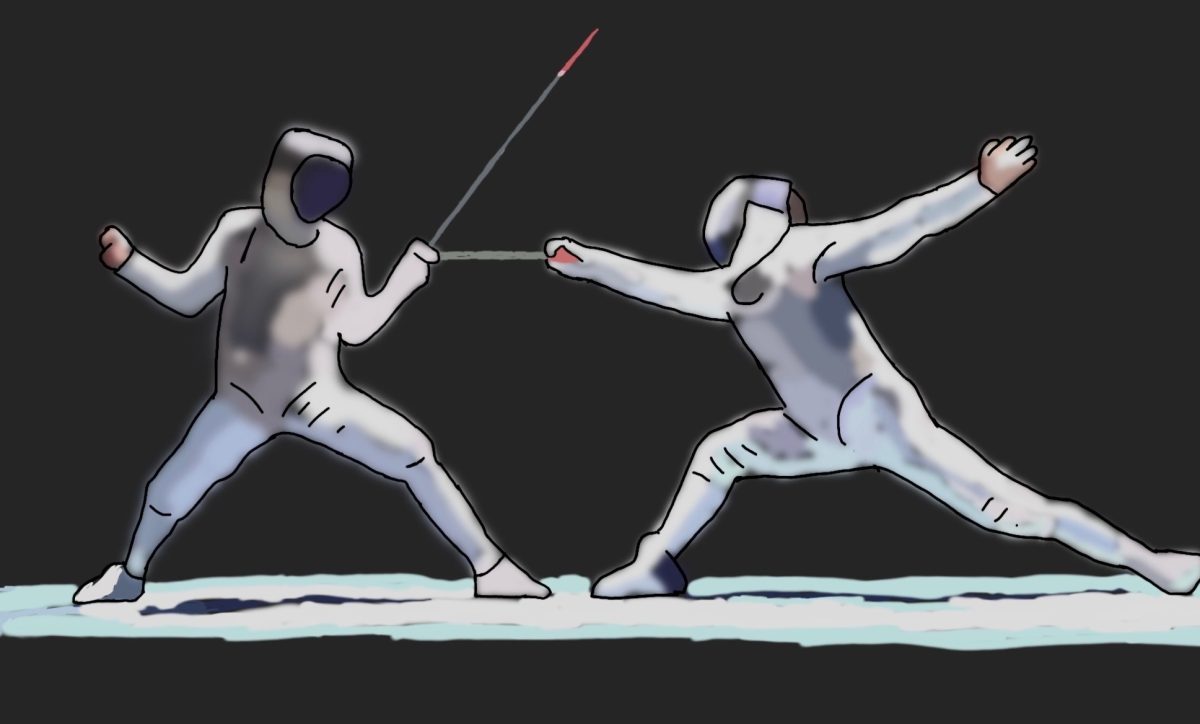

The cycle extends beyond national politics and into local institutions as well. The same social construct diminishing women’s power in government is also evident at Poly. Over the past ten years, only one female student has held the position of Associated Student Body (ASB) president.

Thus, because of the social construct that requires women to tone themselves down, boys at Poly frequently have a greater chance of appealing to the student body. There also may be other, more subconscious explanations for why Poly tends toward electing boys for ASB president. For instance, by seeing the continuous election of men over women in the federal government, students may inadvertently believe that men are better qualified for leadership than women.

Year after year, the student body unintentionally buttresses the same stereotypes that contribute to gender disparities in government at the national level.

Women’s underrepresentation in top political positions continually enhances the stereotype that leadership is a masculine trait and, therefore, disadvantageous to women who aspire to the presidency.

As a democratic society, the population must act on this imbalance. At Poly, students can interrogate their values and biases and reconsider the qualities they value in their leaders. This raises a fundamental question: what values are guiding our votes? Currently, we value assertiveness for leadership, traits typically associated with masculinity. If we fail to model inclusivity and gender equity now, we risk bolstering the barriers that have historically barred women from positions of power.

According to McClelland-Cohen, “Students can ask themselves if they are voting because the candidate is funny and charismatic, or the candidate makes a genuine, compelling case about leadership.” Such introspection is not unique to Poly but to any community striving for equity.

Increasing gender equality in the grand scheme of politics may seem impossible, but we can start at Poly. For instance, when we vote for the ASB president, we should consider that society often “trains” girls to be quieter, in comparison to boys who never had to face that social construct. With this perception in mind, we can vote for the person who truly presents the best ideas and methods of execution rather than the person who is the loudest or funniest. By recognizing our biases and shifting our priorities, we can begin to alter the gender dynamics at our school and, hopefully, in our communities.