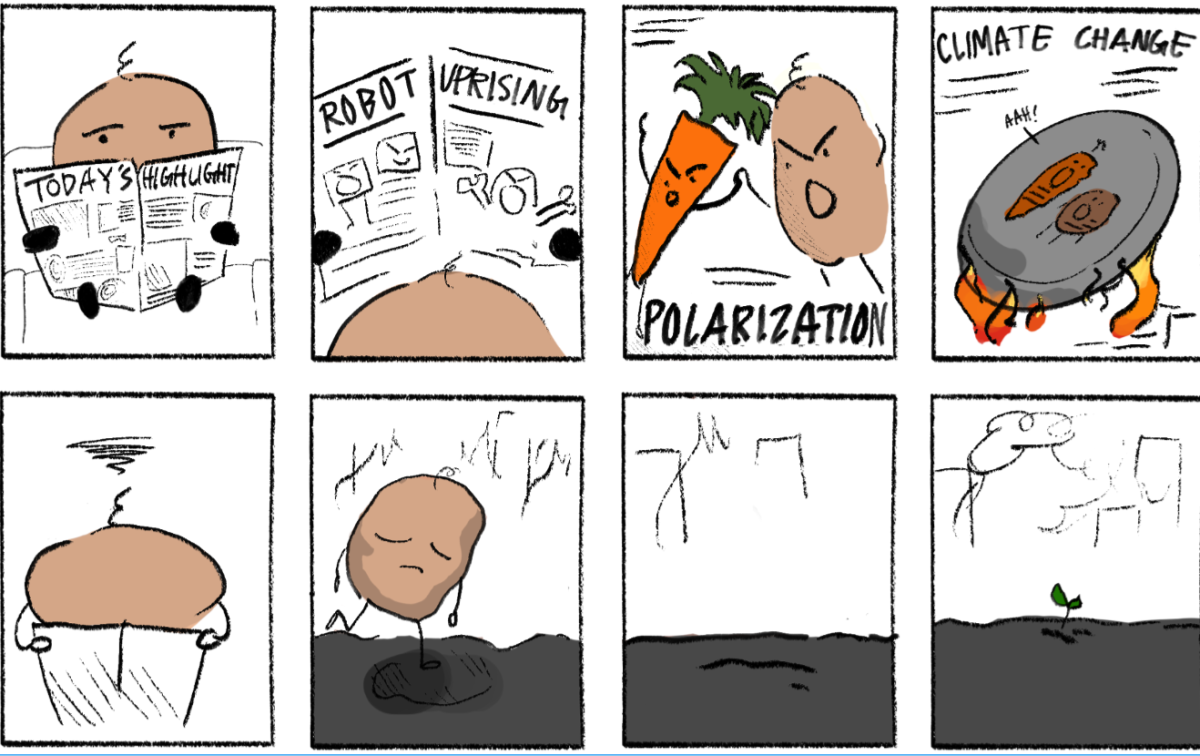

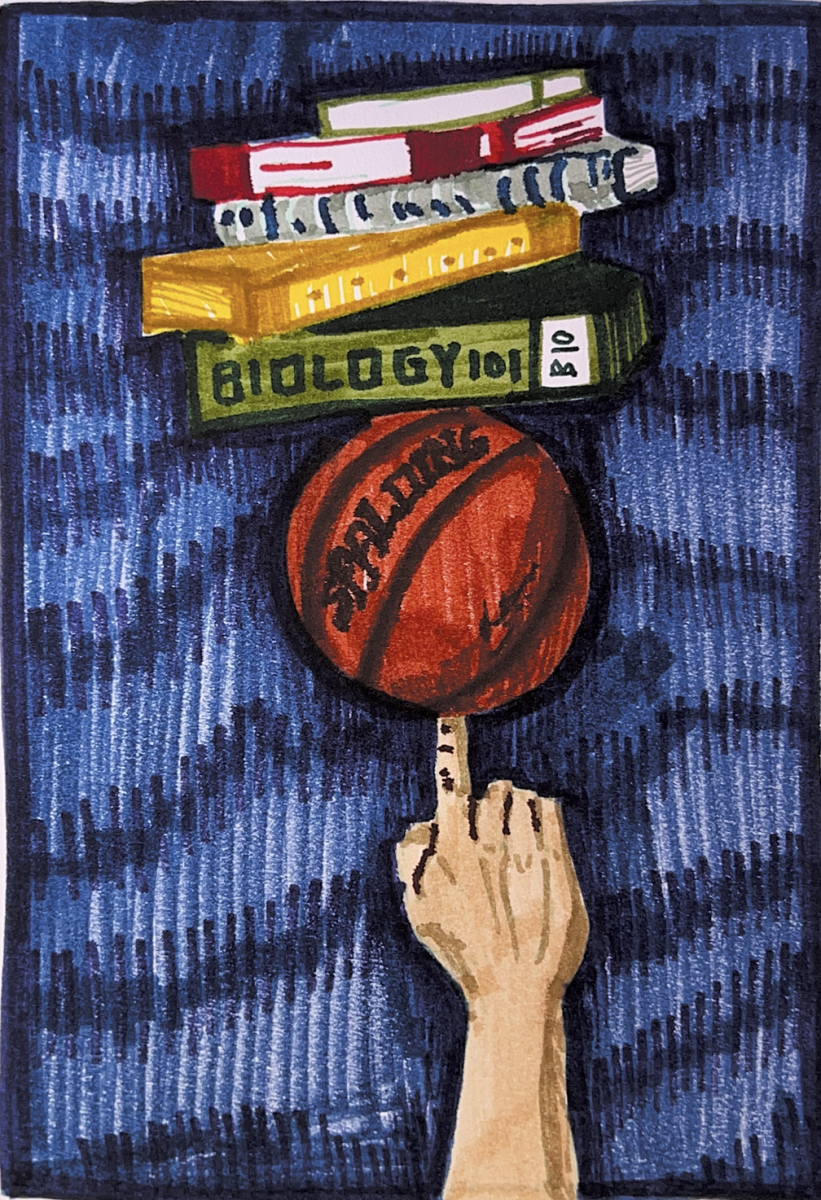

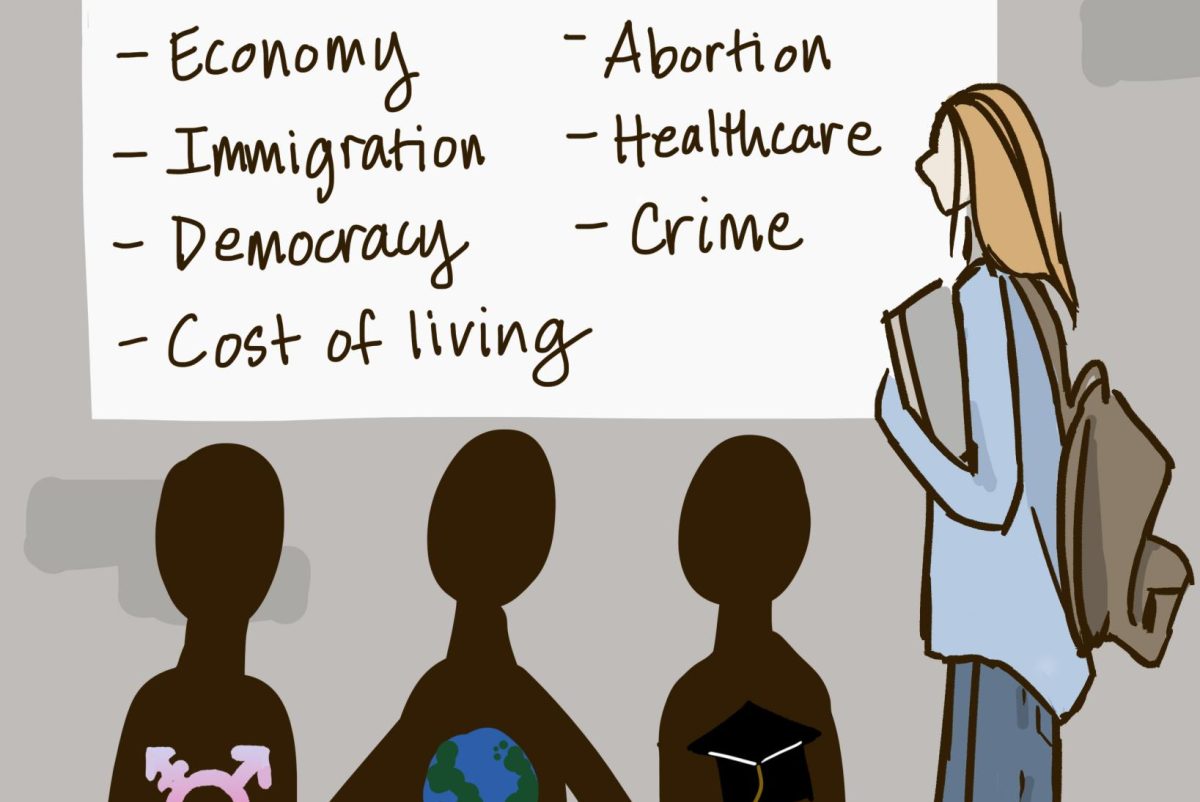

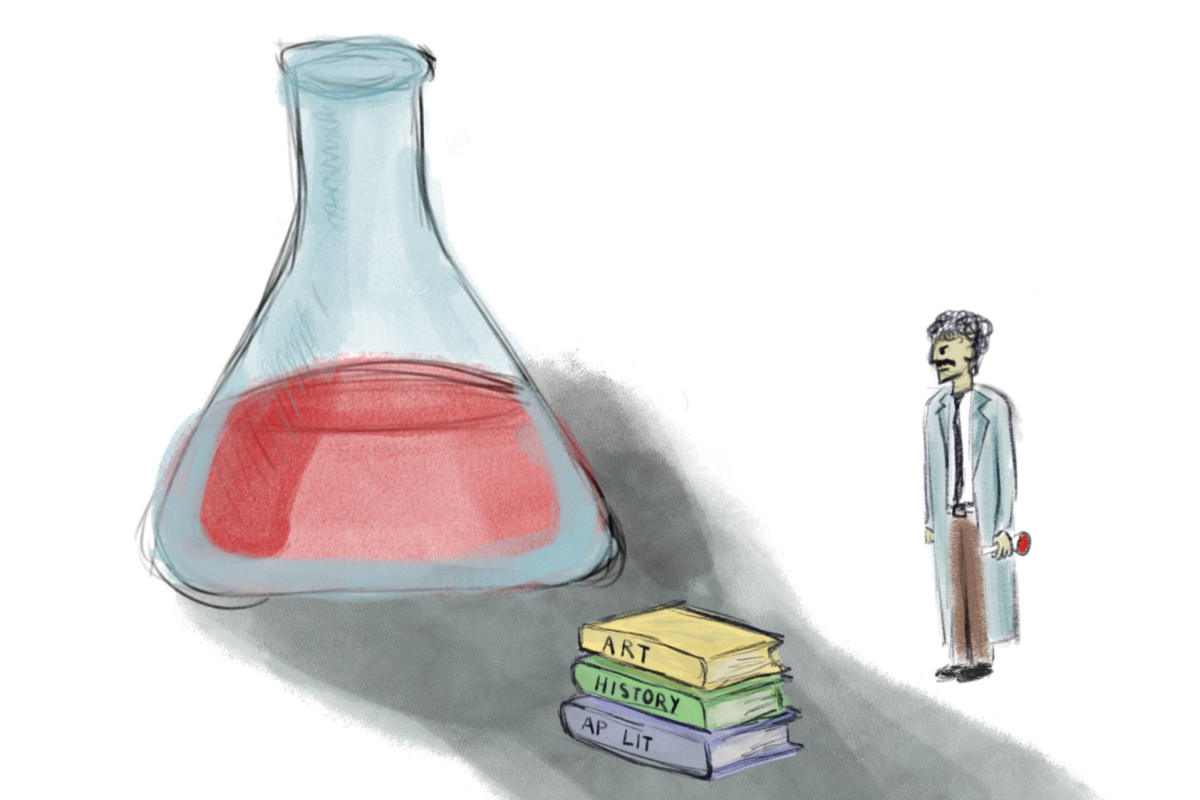

When faced with the task of describing themselves as students, high schoolers often place themselves in one of two categories: humanities or STEM. In the past decade, we’ve witnessed a dramatic uptick in the latter, whereas the number of students passionate about literature, history and the arts has dwindled to new lows. While claiming to be either a humanities lover or a STEM kid is in no way a binding contract, multiple indicators point to a clear trend: the humanities are facing a crisis.

According to The Atlantic, the number of history majors has decreased by 45% since 2007, and English has plummeted by half since the mid-1990s. Additionally, the New Yorker cites a mere 7% of Harvard University’s 2022 freshman class expressing an intent to pursue the humanities — a significant drop from the reported 20% in 2012 and the nearly 30% during the 1970s. The data crystallizes the narrative: we are becoming disengaged with the humanities. But why is that the case?

Our disinterest in the humanities lies largely with a shift in how we approach education. Today, students approach school with a utilitarian mindset that values monetary potential over intellectual fulfillment. While there are undoubtedly people who derive genuine excitement from studying math, science and technology, a fair share of students are propelled to pursue STEM majors because they believe such a path will set them up for more lucrative careers. As the Pew Research Center notes, “About half or more of the general public – whether they are employed in STEM or non-STEM jobs – believe that STEM jobs pay better, attract more of the brightest young people and are more well-respected.”

Granted, adopting a practical approach to school is not innately wrong; there are certainly those without the financial leeway to choose a degree for intellectual interest alone, and rising student debt necessitates that many of us think about our financial futures with pragmatism. However, despite popular opinion, a degree in the humanities is not “worthless.” In a survey conducted by the Association of American Colleges and Universities, 80 percent of employers voiced that they prefer candidates with a robust liberal arts foundation, emphasizing the importance of soft skills found in the humanities.

While STEM graduates typically earn higher salaries than their peers, their edge wanes within the first decade in the workforce. Meanwhile, the qualitative and abstract skills that humanities courses confer — critical analysis, original research, writing proficiency and even empathy — transcend fluctuations in the job market and remain valuable across time periods.

More significantly, evaluating school solely through a lens of applicability and “usefulness” neglects the intrinsic value of education: learning for the sake of learning. The beauty of the humanities lies in its acknowledgment that intellectual pursuits bear fruit in far more ways than financial payoff. Sophomore Kelly Zhang expressed, “I like that you are always a work-in-progress in the humanities, specifically English. When you write something, there is always room to improve, and it makes you want to keep learning.”

Today’s society has lost sight of the fulfillment behind learning — the essence of what it means to be a student and what it means to engage with the humanities. Whenever someone inquires about my favorite subject, and I reply with “English,” they almost always follow up with a probing question about how I plan to make money, and when I express an interest in creative writing, they are quick to point out its futility.

In short, there is a prevailing apathy toward what renders the humanities so intriguing and fulfilling. Sophomore Hudson Yen noted, “I find STEM more gratifying since there’s always one clear answer. In the humanities, there’s a lot more up for interpretation.” Sophomore Akhil Venuturupalli concurred, “I like how everything in math and science can be proven.”

While there is comfort to be found in the “one answer” reliability of STEM curricula, the subjectivity of the humanities is largely why those classes are so intellectually engaging: they force one to be an analytical, curious person. Senior Melody Huang stated, “I like humanities courses because they are more discussion-based, and I feel like I can talk through my thoughts. Whereas, in STEM classes, sometimes it feels like I am just being taught topic after topic. I feel like dialogue and discussion [in humanities classes] help me to connect with my classmates more.”

The liberal arts matter because how we think matters as much as what we learn. Even prestigious, STEM-tilting academic institutions agree; Caltech, a university praised globally for its scientific programs, mandates that graduating students take at least 18 units of advanced humanities courses.

I’ve loved the humanities classes I’ve taken thus far at Poly, and I hope that other students, regardless of whether they favor STEM subjects or not, can recognize and appreciate the inherent value of a humanities education. While students often stake their claim in the STEM or humanities camp early in their high school career, feeling tethered to their choice, it’s not too late to ignite an interest in English, history, philosophy or the arts. As junior Katie Sam shared, “I started my Poly career in ninth grade, and I thought I was very much a STEM person. But, this year, I was fortunate enough to take on leadership roles in humanities extracurriculars and clubs. I realized that I actually enjoy humanities as well.”

Our collective reevaluation of the humanities is essential, and recognizing that their benefits are on par with those found in pursuing STEM is vital. It is time to rediscover the richness of an education that embraces the humanities as a vital component of being a student and a human being.