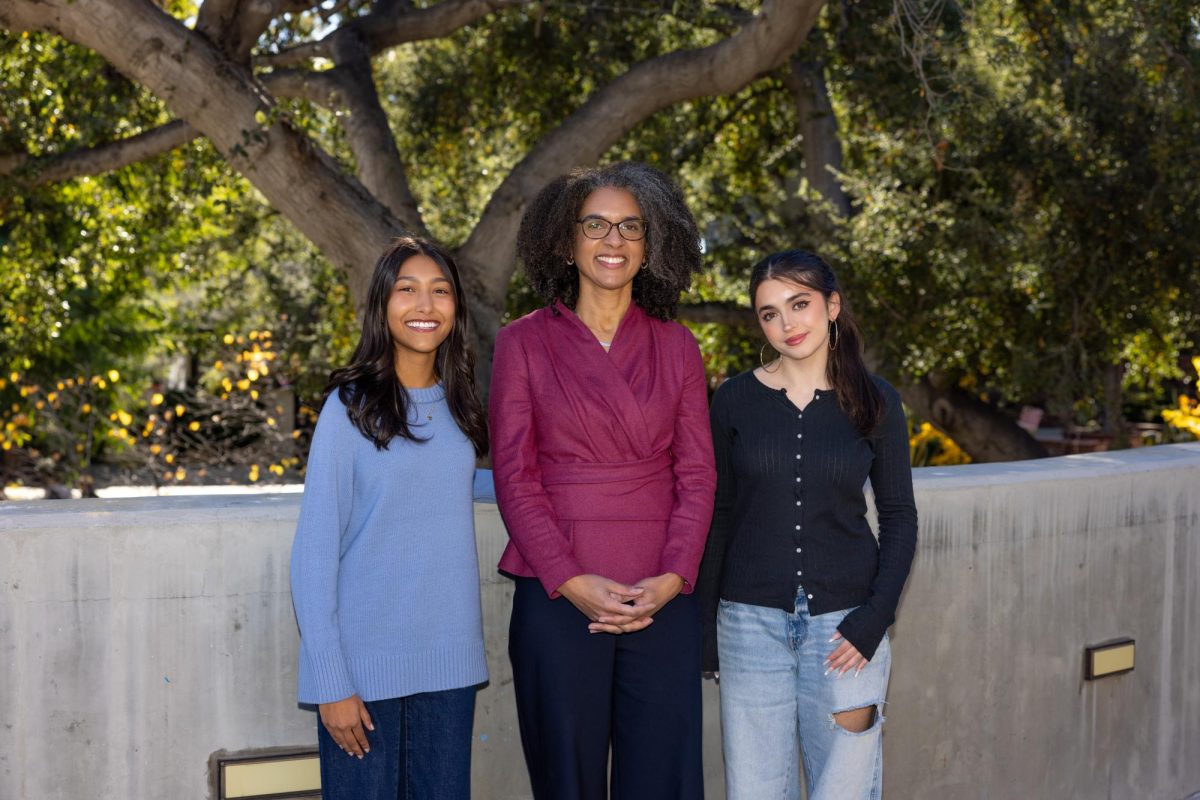

On Thursday, Apr. 17, Lina Lenberg, a part-time professor at the University of San Francisco, visited Poly as part of the PolyGlobal series to discuss the ongoing genocide of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, an autonomous region of China. Lenberg, a Uyghur Genocide Advocate with the California Collaborative for Holocaust and Genocide Education, has traveled across California raising awareness about the Uyghur crisis.

Upper School Math Teacher Amber Bocquin invited Lenberg after meeting her last summer at a USC teacher conference on Holocaust and genocide education.

“It’s very important for me to raise awareness, so I sought her out to bring this discussion back to Poly,” Bocquin shared. “It’s been two years since we last had speakers discuss this genocide at Poly, and unfortunately, it receives little recognition, so I think this was an important opportunity to do so.” Lenberg began by explaining the Uyghur people’s history, rooted in East Turkistan, also known as Xinjiang. She described how, although China officially recognizes 56 ethnic groups, the government prioritizes the Han majority socially, politically, and economically. Using propaganda to portray Uyghurs as terrorists, the government justifies mass surveillance, systemic oppression, and the internment of Uyghrs in “reeducation camps.”

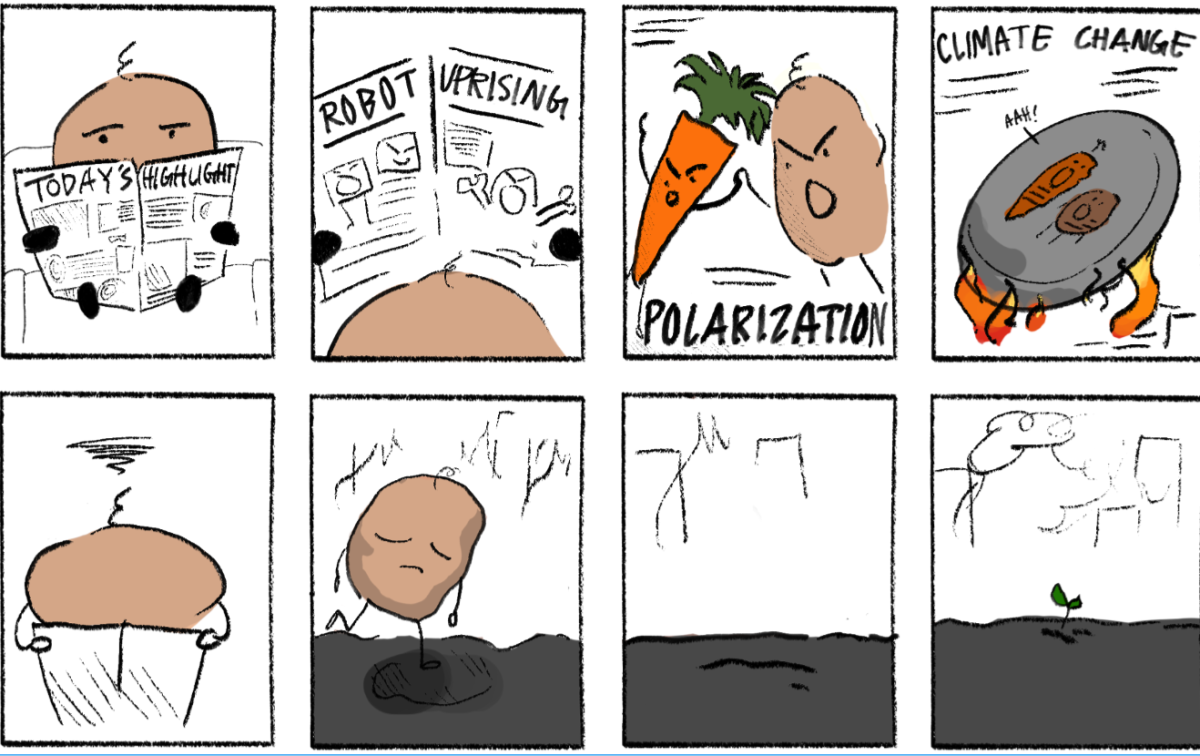

Lenberg also addressed how the Chinese government denies these actions, one of the ten stages of genocide. Many countries, including Russia, Pakistan, North Korea and Iran, have remained silent or denied China’s crimes to preserve trade relations. The United States, however, has formally recognized the Uyghur genocide at the federal level, though more action is possible. “

My biggest takeaway was that the biggest problem with the Uyghur genocide is the lack of awareness and knowledge surrounding it,” noted junior Alex Chui, who attended the event. “As students, we are also responsible for spreading awareness about it.”

Lenberg ended with a Q&A session, during which she encouraged the boycott of products made in China as one way to protest and create economic pressure on the Chinese government. She also stressed the importance of separating criticism of the Chinese government from Chinese people, who often face persecution if they speak out.

“I hope students can understand that there are some really horrible things that we need to know and talk about, and we can do it in a way where we aren’t overwhelmed or overburdened so that we feel powerless,” Bocquin reflected. “Instead, these genocide conferences should make us more encouraged to push for change.”