On Tuesday morning of Rivalry Week, instead of the usual hustle and bustle that takes place before the community time performances, Upper School Director José Melgoza and Director of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Michaela Mares-Tamayo stepped onto the Garland stage, and the usual energy of the week shifted to silence. Melgoza announced that there would be a pause in rivalry activities that day because, the day prior, a teacher had reported that the N-word had been graffitied in the Fullerton boys’ restroom.

The reactions in the audience as Melgoza and Mares-Tamayo spoke were varied. Some seemed shocked while others laughed and giggled, but for the majority of students, I wouldn’t say this incident was surprising. It wasn’t some outlier. It reflected the culture of our community.

During the assembly, Melgoza emphasized that the use of hate speech directly violated Poly’s values and commitment to inclusion, and he stressed the importance of reporting incidents to faculty, noting his disappointment that no student had reported the hate speech before the teacher found it.

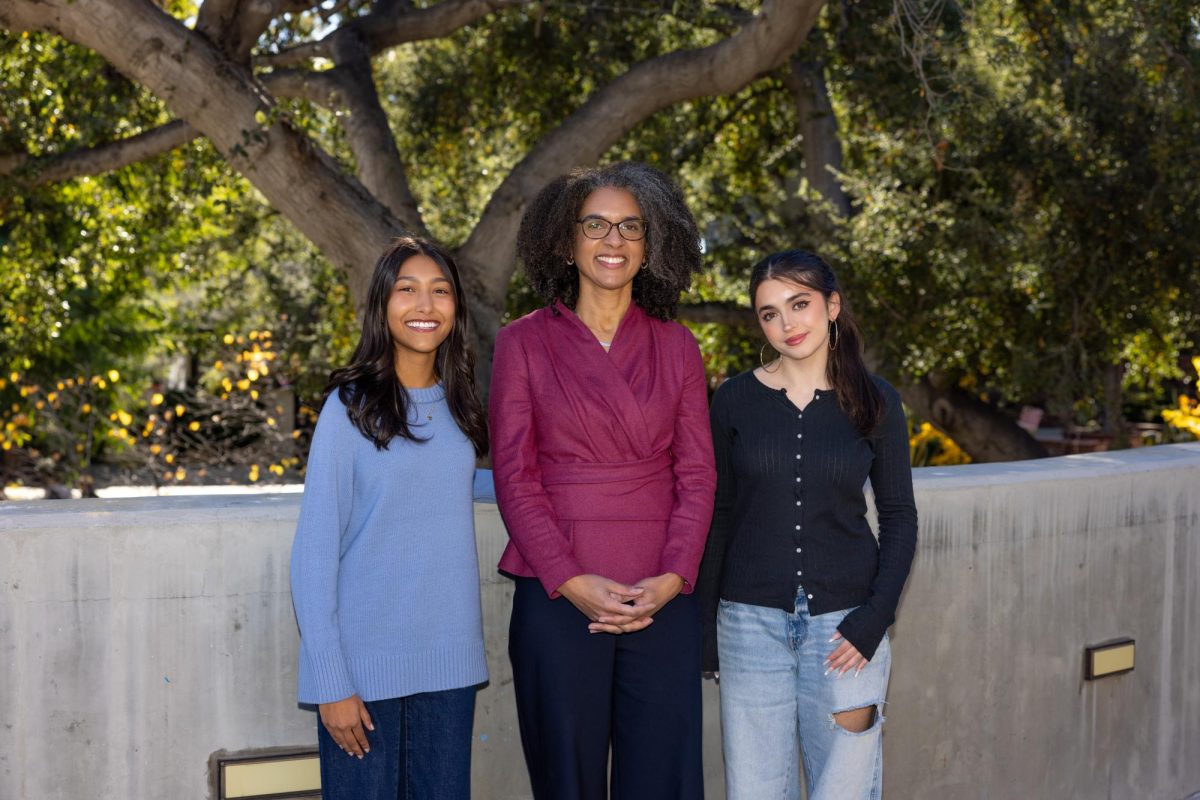

Mares-Tamayo spoke about the harm this language causes and reflected on her own time as a student at Poly in the late ’90s, noting that while such incidents might have been more common in the past, she had hoped the school had since moved beyond them.

The N-word carries a long and violent history. Originating during the transatlantic slave trade, the word was used to dehumanize Black people and became a symbol of systemic racism through segregation, hate crimes and everyday discrimination. Today, its use continues to perpetuate legacies of violence and exclusion.

As a co-leader of the Queer-Straight Alliance and a gay student who has experienced homophobic comments firsthand and heard slurs directed at my community on campus, I wasn’t surprised to learn about the graffitied hate speech. Although this incident was one of few reported to administrators, it is one of many instances of hateful language targeting ethnicities, religions, sexual orientations and gender identities on campus. Yet, in the past four years of my time in the Poly Upper School, we have never had a dedicated assembly or advisory time to discuss this, so the March assembly felt long overdue.

Unlike when hate speech is spoken, which often slips under the faculty’s radar, written words are harder to ignore. This time, the hate was literally written on the wall, one day before an admitted students event. It was incumbent on the administration to address it before the whole Upper School, but it was also a stark reminder that hate speech has never left campus. In the days following the assembly, students have come forward and reported other instances of hateful language and symbols graffiti elsewhere on campus.

When I asked Upper School Dean of Students Jennifer Cardillo whether additional reports had been made, she replied, “Yeah, so there were a few things that then got moved, cleaned, sanded down, and those were actually kind of in the cluster of concerns that [Mr. Melgoza] raised in Garland.” Referring to the markings, Cardillo explained, “Things had perhaps been sitting there for years without anyone reporting them—just sort of maybe noticing them, being terribly offended by them, but not actually bringing them forward. I think in those cases, they were in places where they weren’t visible to adults, or the adults didn’t have that awareness.”

When I interviewed Melgoza after the assembly, he stated, “This is ongoing. It doesn’t just stop. We don’t sweep it under the rug. We have to keep talking about it as a community.”

When asked about the administration’s response to the incident, Melgoza said, “The situation was unacceptable, period. Someone had to feel like they weren’t going to get in trouble doing that. I know it’s difficult for things to come up to the administration. And that’s why it’s important when we do that, we act swiftly. When I go up there and I say that I want us to be a kind, loving community for everyone in our community, to feel safe, that this is their home—I mean that.”

Following the assembly, Melgoza sent students to their advisories and asked them to complete a reflective writing on the incident before discussing. He urged any student with information about the incident to share what they knew with an adult.

Melgoza explained, “Those [reflections] were submitted to Ms. Cardillo and me, and we read through them. I spent spring break reading through those reflections, looking for some sort of feedback that could help us figure out what the next steps are, with a glimmer of hope that maybe the person who wrote the word would be revealed, but they weren’t.”

He added, “I think those moments of reflection are super important because they give the administration an opportunity to understand the heartbeat of the community.”

Reflection is an important starting point. However, it’s important to note how common discriminatory language, including racial and ethnic slurs are on campus.

Two weeks ago, I sent out a survey to the Upper School student body. 96 students responded, helping to reveal just how common the use of hate speech is within our community. The results confirmed what many of us students already know: hate speech isn’t rare — it’s a regular part of life at Poly, both on and off campus.

73.7% of students reported personally hearing or seeing peers use discriminatory language regarding race or ethnicity in school settings. 62.6% had witnessed peers use discriminatory language related to sexual orientation, 55.6% had witnessed peers use gender-based discriminatory language and 44.8% witnessed peers use ability-based discriminatory language. 64.7% said they witnessed Poly peers using discriminatory language outside of school as well.

When asked whether they believed Poly effectively addresses harmful language, only 32.3% of students said the school handled it “extremely” or “somewhat” effectively while 42.7% of students said Poly handled it “not very effectively” or “not at all effectively,” and 25% responded “neutral.” Yet, only 13.1% of students reported ever informing a teacher or administrator about an incident. Out of responders who stated they did report an incident, 73.7% were not satisfied with the outcome of that report.

Indeed, while almost all of us students hear discriminatory language at Poly, administrators such as Melgoza and Cardillo report that very few incidents are formally brought to administration.

“It’s almost never happening,” Cardillo said. “Really, the reports we have had are things that adults have witnessed.” She emphasized the importance of students speaking up: “We cannot address it if we don’t hear about it.”

Cardillo also highlighted that the harassment and discrimination policies were recently updated to remove ambiguity.

“If language is harassing, we defined what that looks like, including things that people would say are just a joke,” Cardillo explained. “If something is said and we have evidence of it, then there can’t be a question of, ‘Well, I didn’t know: I thought this was just a joke.’ We’ve added language that allows us to take serious action when we know about something, and now we have to figure out what would allow students to feel that they can bring things to us, or, you know, sort of trusting that we will handle things well when they do.”

Nevertheless, reports remain very rare. “In terms of hateful language, there was one circumstance that was brought to me this year,” Cardillo said. “Student reports, I can count on one hand—and I’m not going to be using many of my fingers.”

Sophomore Julia Swanson is one of the few students who have raised concerns with the administration multiple times this year. She described feeling frustrated that students who call out hate speech are sometimes seen as “villains” by peers and that it often falls on students rather than adults to address harm.

Swanson explained that her brother, Cole Swanson ‘19, shared that when he attended Poly, he recalls some adults addressed the use of hateful language more directly. Swanson stated, “Teachers like [former Dean of Library and Learning Commons and 9/10th Grade Dean] Aquita Winslow would call students out in morning meetings if they said inappropriate things or said the N-word. We need people in the administration to put their foot down and say that this is not appropriate, and you’re going to be called out for it.”

Black Student Union (BSU) President Akira Brown, a senior, expressed a similar sentiment about the broader culture at Poly when I asked her how she had seen perceptions of safety and respect evolve in the past four years among Black students on campus. “I would say that no one feels unsafe in a physical sense, but respect has been an issue,” Brown said. “When tough topics come up, Poly students tend to laugh, which shows a lack of respect, even if it’s not intentional.”

Freshman Amira Shamsi observed that the casual use of slurs and harmful language has become more normalized in her grade. “It’s so casual for them to do stuff like that,” she said. She added that while assemblies like the one in March are important, they are unlikely to have a lasting impact without deeper, long-term education.

Shamsi pointed to her English class, where students are currently reading “Kindred” by Octavia Butler, a novel that deals heavily with themes of racism and the legacy of slavery. Discussions about the book have created important conversations and more spaces where students can learn about such topics seriously.

Curriculum can really be a powerful tool. However, as Swanson mentioned to me in an interview, “Even in classes that talk about social justice issues, comments and jokes are made by students, and teachers just let it go.”

Across different grades and experiences, my peers shared that many instances of harmful language are treated as jokes, and while many of them may not be rooted in bad intentions, I think it is important to note that no matter the intention behind saying something discriminatory or offensive, it still is discriminatory or offensive.

When asked about the use of slurs among the seniors, Reza Mohammed, senior and co-leader of the Muslim Student Association, said, “In our grade, I don’t really hear the N-word said by non-Black people, but other slurs are used, and although it’s ignorant and offensive, I don’t think they’re made with malicious intent. I don’t know if people necessarily always have bad intentions, but it’s definitely something that needs to be fixed. And it can’t be something that pervades, because the more it’s used, the more comfortable people become, and then it’s used in a derogatory way.”

Latinos Unides and Respect Our Migrant People Everywhere leader Alyssa Cobian, a senior, echoed these experiences. “The jokes really catch me off guard,” she said. “It’s not just about Latinos either. There are jokes about women, different sexualities—all these jokes have a presence, and these jokes reveal the normalized racism and homophobia in our community.”

Administrators like Mares-Tamayo recognize that harmful language often reflects larger societal issues. “We strive toward inclusion, but there’s so much exposure to messaging that normalizes exclusion,” she said. “It seeps into our daily interactions, often without people realizing the harm their words can cause.”

Plans for a more formal, accessible reporting system are underway, aimed at helping students report incidents with greater clarity and confidence. Mares-Tamayo explained to me that the administration is working on creating a concrete process— a survey students can easily access to make sure reports are not just passed along informally but instead reach key Upper School leaders directly.

“If we have a concrete form that’s accessible and available to students, they can fill it out and know that it’s not just disappearing into the air,” she said. “It will go directly to some of our Upper School leadership: specifically Ms. Cardillo, Mr. Melgoza and myself.”

While administrators need to continue working on ways to make reporting easier, we students must take matters into our own hands and strive to create an inclusive community. According to the school’s harassment policy, verbal harassment, including the use of slurs, is prohibited and can result in “appropriate corrective action, including discipline up to and including expulsion.” But while the policy lives on paper, our experiences on campus show that verbal harassment remains a largely unaddressed issue.