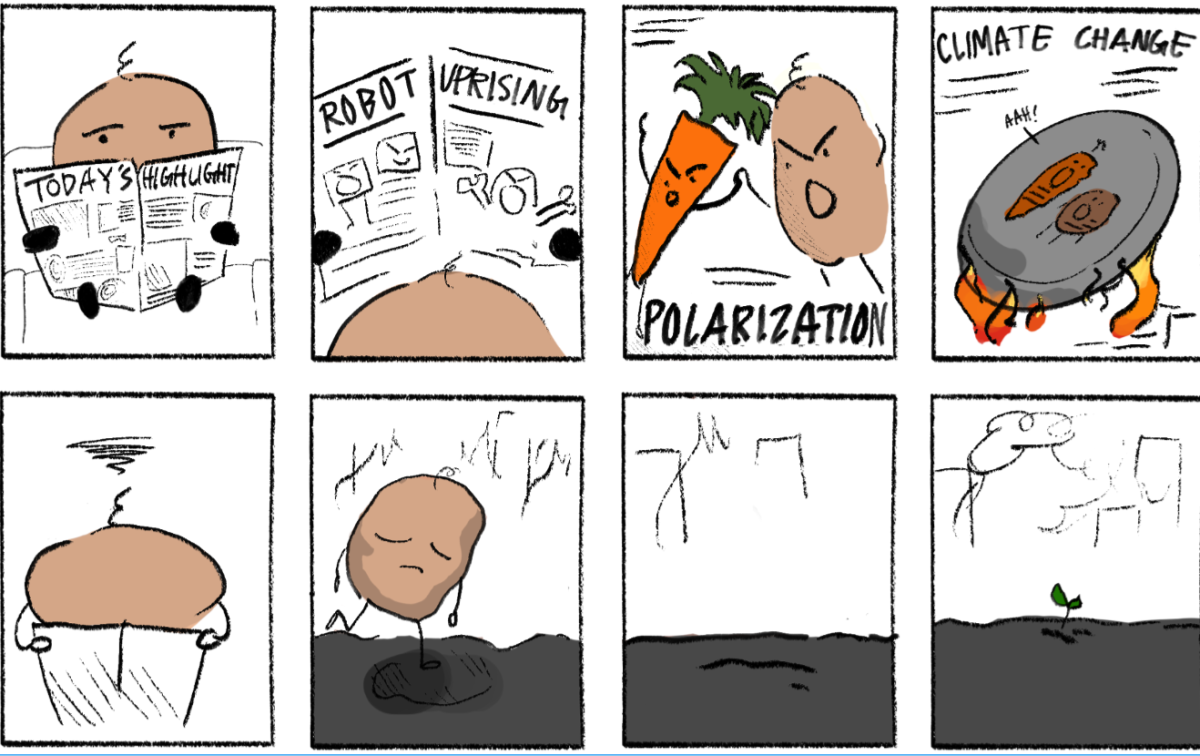

Talking about climate change can feel like listening to a broken record, except instead of a catchy tune, it’s just scientists yelling, “We’re running out of time!” on repeat. Scientists hope to stir up fear and, thus, action. Yet, this repetition of doom and gloom has the opposite effect. Many students view climate change as something analogous to a futuristic zombie apocalypse they watch on Netflix, but not one that is realistic in the status quo. Moreover, scientists and professors often present climate change in a complex or distant way, making it difficult for average, everyday students to understand its impacts. Academic language is inaccessible, making it difficult to imagine tangible solutions that the average person, especially the average teenager, can strive towards.

Freshman Aidan Shih shared, “I don’t feel scared by climate change, not in the same way that I would be scared by an imminent threat like a bear. Degrees or fractions of degrees don’t feel terrifying. They don’t feel real. If there’s nothing we can do to make them feel real, then we need to change our entire approach.”

It’s time for a shift in how we present climate change. Currently, the way we discuss climate change—both here in our own school community and in society as a whole—often fails to inspire action. But what if climate change wasn’t just another lecture or news headline depicting the end of the world? What if we stopped talking in distant numbers and confusing calculations? People should know that climate change isn’t some far-off issue that will only affect polar bears; it’s happening now, and it’s shaping the world students rely on. The key is making it feel relevant, engaging and personal—something that can start right here at Poly.

This past month, author and assistant professor at the University of Cincinnati Abel Gustafson spoke to Poly’s Climate Change class about the major pitfalls in climate communication: focusing too much on distant, symbolic imagery (like sad polar bears) and emphasizing fear over practical solutions. For example, while the news that “Antarctic CO2 levels hit 400 PPM for the first time in 4 million years” is a significant climate milestone, most people do not grasp the urgency or implication embedded in the scientific terminology. On the other hand, apocalyptic imagery, such as posters of Earth melting like ice cream or frying like an egg, reinforces a sense of inevitable catastrophe. Both have the same effect: students do not jump into action either because they don’t feel the need or because they feel overwhelmed.

Upper School History teacher Avi McClelland-Cohen, who teaches the Climate Change elective, sees a parallel between Gustafson’s concerns and actions at Poly. “Many Poly students feel disheartened and disempowered by the way climate change is taught,” McClelland-Cohen explained. “As a society, we are communicating poorly about it. Most students at Poly actually care about climate change but aren’t talking in ways that help.”

The overwhelming emphasis on crisis, rather than solutions, leaves students feeling stuck rather than motivated to take action. Laura Fleming, Manager of Environmental Sustainability at Poly, emphasized the importance of making climate solutions tangible.

“In terms of initiatives at Poly, I think communicating about the work we are doing is an important aspect of this work,” Fleming said. “We have published many articles in PolyNews over the last three years, communicating to the Poly community about sustainability initiatives and how our students are helping to drive these sustainable changes. We also created a Climate Action page on Poly’s website that lives under ‘Campus Life.’ I do think we could do even more to communicate to Poly students. It would be great to see a sustainability assembly in the Upper School that occurs at least once a year and find ways to weave in mini-sustainability lessons in morning meetings.”

As Fleming noted, our school has taken meaningful steps toward sustainability. The recent installation of solar panels reduces the school’s carbon footprint and demonstrates a commitment to clean energy. The composting system, which diverts food waste from landfills, helps cultivate nutrient-rich soil while reinforcing responsible waste management. Additionally, the introduction of a reusable plates and utensils system in the cafeteria significantly cuts down on single-use plastics, and the food sorting system has already been integrated as a part of school lunch. Recently, we implemented Hugelkultur, a regenerative gardening technique now in place on Arden Lawn.

Despite Poly being a leader in sustainability initiatives, there are still ways that we can improve. For example, the school can integrate discussing climate change across academic subjects, making it a part of everyday discussions. While science classes cover the basics, climate change has broader social, ethical and cultural dimensions that could be explored in many interdisciplinary studies. While certain English courses emphasize environmental subjects, such as the nature unit in AP English Language and Composition, Poly should integrate explicit conversations about climate change in classes across all subjects. This could manifest in case study assignments in the 9th grade World Religions class, such as linking Hinduism and Islam to environmental stewardship to help students understand sustainability through different cultural perspectives. Climate change discussions could also be integrated into the advisory program or Human Development curriculum, spaces that could foster informal yet educational discourses on sustainability.

Beyond the classroom, climate conversations, focused on solutions rather than doom and gloom, should extend into students’ personal lives, particularly on social media platforms like Instagram. Integrating climate change into familiar spaces and using conversational language can encourage even the most apathetic or uninformed students to pursue climate activism. A handful of thoughtful Instagram stories or TikTok videos could make all the difference, drawing others into the subject of climate change in a way that feels natural and accessible. Students can synthesize what they learn at Poly and change the way they discuss climate change with those outside of school—their friends, parents and siblings.

Climate change communication is not just about presenting facts—it’s about making those facts resonate with people. If we want to see real change, both at Poly and beyond, we need to rethink how we talk about it. Let’s shift the conversation from polar bears and apocalypse to empowerment and collective action.