Whenever I spoke with my grandfather, he always asked me the same question: “Have you studied Iran in school?” Invariably, my answer was “no.”

My grandfather, who immigrated from Iran to the United States as a young man, was immensely proud of his culture, and he wanted his grandchildren to learn about his home country. Although my answer never changed, his question has continued to echo in my mind as I have searched for Middle Eastern studies at Poly. What I have found is this: not only Iran but the entire region—and especially any events from the past century—is conspicuously absent from the History curriculum.

Up until five years ago, Poly offered a course on the Middle East as part of World Cultures, a semester class formerly required for freshmen, consisting of four sections offered on a rotational basis: Africa, India, Latin America and the Middle East. Students chose which section they wanted to take from the options available in a given year. The World Cultures class ended in 2019 and was replaced by World Religions in fall 2020.

The World Religions curriculum includes the Abrahamic religions—Christianity, Islam and Judaism—all of which originated in the Middle East. However, the course focuses on the core tenets of religions; it is not an area studies class.

History teacher Lawrence Zellner explained the rationale for switching from World Cultures to World Religions: “It [World Cultures] wasn’t a consistent ninth grade experience.” He added, “We conceived [World Religions] partly because we saw there’s a general need in our world for more religious literacy, particularly in our part of the world, which happens to be a fairly liberal pocket and a fairly secular pocket.”

Indeed, religious studies are crucial to understanding the world today—particularly the Middle East. World Religions offers students a foundational understanding of the religious history of the region. Poly students could apply this theological knowledge in a present-day context if given the opportunity to study the modern Middle East.

Yet, when I entered Perspectives on Modern World History in 10th grade, I found that the Middle East was strangely missing from the curriculum.

Senior Ava Taylor, who co-leads the Middle Eastern Affinity Group, shared this sentiment: “Since sophomore year world history, I’ve been noticing that we don’t learn about the contemporary Middle East. And I thought that was world history, but even then, we only learned for a little bit about Ibn Battuta.”

In addition to being largely left out of the Modern World History class, the modern Middle East is virtually nonexistent everywhere else in Poly’s curriculum. Recent course offerings include African-American History, East Asian Religion and Philosophy, Modern China and Modern Latin America—but no class on the Middle East.

In contrast, some peer schools such as Harvard-Westlake and Westridge offer classes on the modern Middle East.

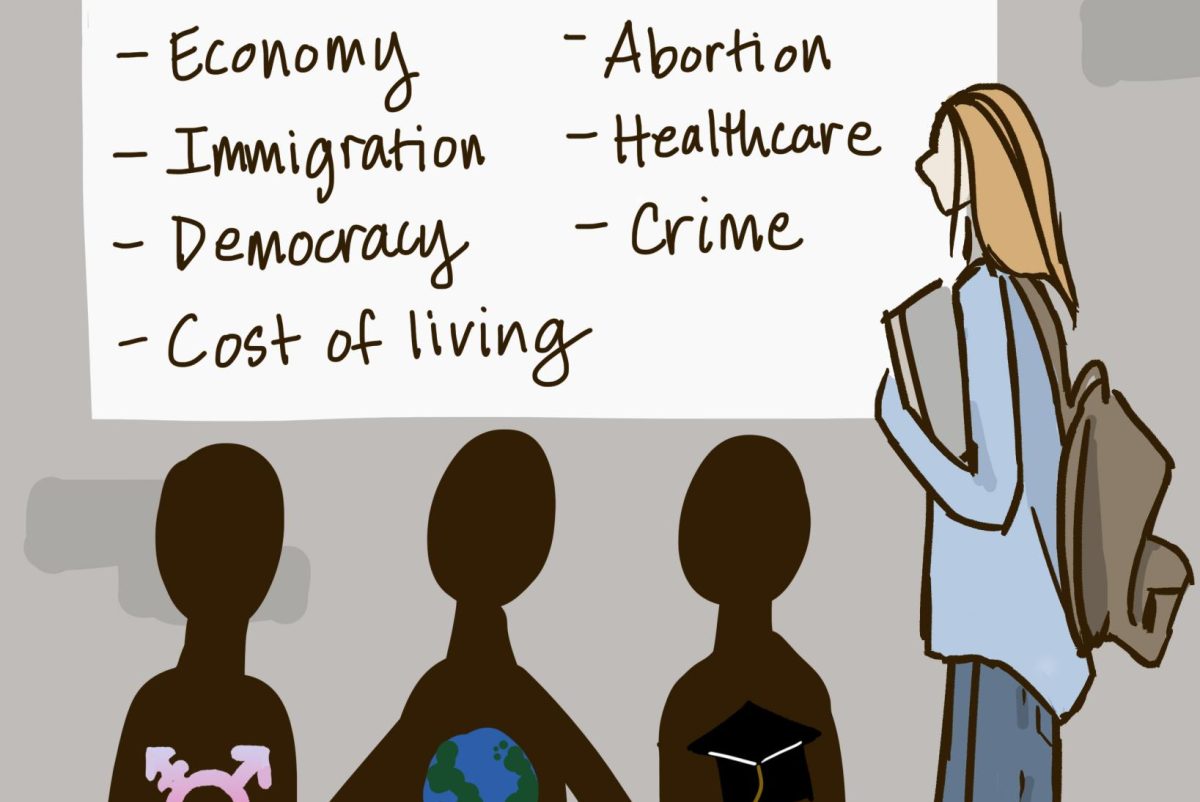

In light of the region’s absence from Poly’s curriculum, upper school students report a weak understanding of the contemporary Middle East. In response to a survey question asking “How well do you feel that you understand current events in the Middle East?” on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being “not at all” and 5 being “very well,” 2% of respondents answered “1,” 29.4% answered “2,” 37.3% answered “3,” 19.6% answered “4,” and 11.8% answered “5.” These are disappointing metrics for a school that prides itself on providing a diverse, global education.

“I was never taught about my own culture growing up and felt very disconnected from it as I was learning so much about other cultures and never my own,” said sophomore Tara Parsa, who co-leads the Iranian Culture Club.

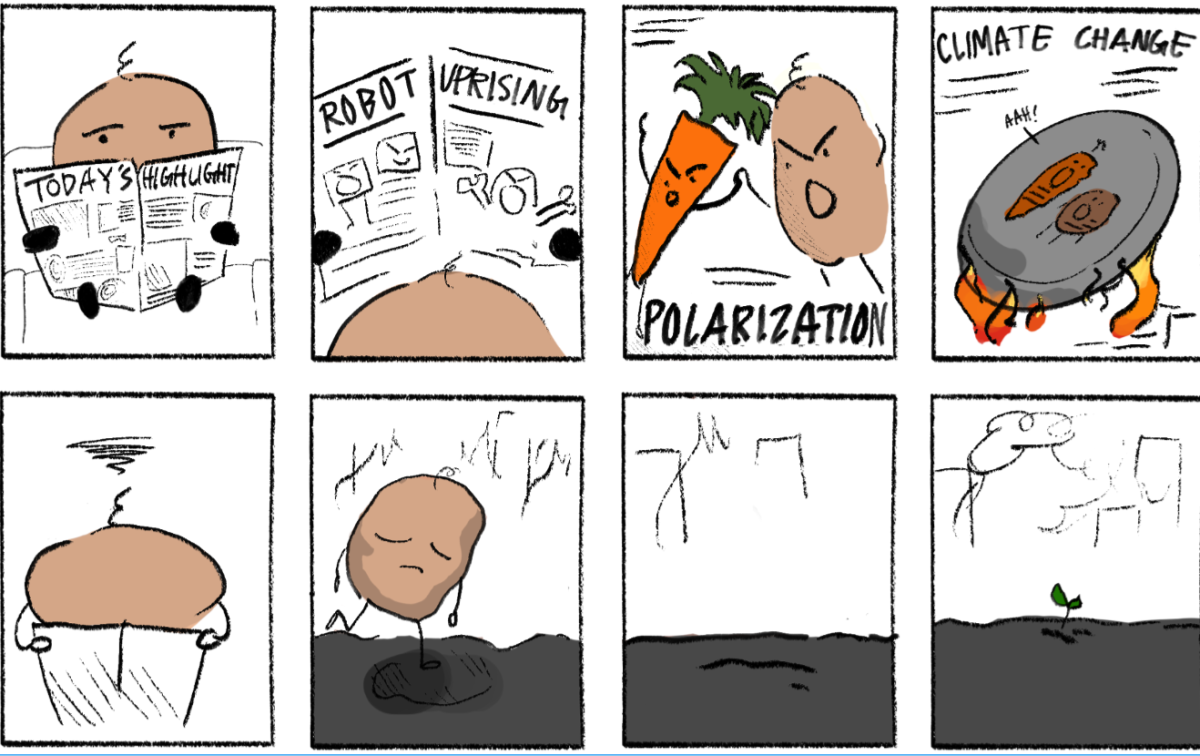

The modern Middle East’s absence from Poly’s curriculum persists in spite of the region’s undeniable global relevance. Since the 20th century, the Middle East has held significant strategic and economic importance due to its abundant supply of oil and natural gas—key resources that power vehicles, ships and airplanes as well as electricity for homes, businesses and industries.

Moreover, as a result of conflict over economic resources as well as religious and territorial disputes, the Middle East is a region of intense international interest and a frequent focus of diplomatic efforts. Thus, the Middle East is key to understanding foreign policy and international affairs.

The region’s significance has only grown over the past year and a half since Hamas’ attack on Israel on Oct. 7, 2023 and the ensuing war in Gaza in which over 50,000 people have been reported killed.

On Oct. 7, 2024, the Armenian Culture Club, Iranian Culture Club, Jewish Student Union (JSU), Middle Eastern Affinity Group and Muslim Student Association met in a closed meeting to discuss the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. During the meeting, students expressed a desire to learn more about current events in the Middle East at Poly, be that through a Middle Eastern studies class or an event for the whole upper school to learn about the conflict.

The affinity groups’ request mirrors the overall opinion of Poly students, many of whom want to understand these current events. In response to a survey question asking “Are you interested in learning more about the modern Middle East?” on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being “not at all” and 5 being “very interested,” 7.8% of respondents answered “1,” 0% answered “2,” 25.5% answered “3,” 35.3% answered “4,” and 31.4% answered “5.”

“I’d like to know more about how resources in the Middle East have affected conflicts,” one respondent shared.

“I think it’d be interesting to focus on other countries in the area like Jordan or Egypt and their reactions to Israel-Palestine,” another respondent wrote.

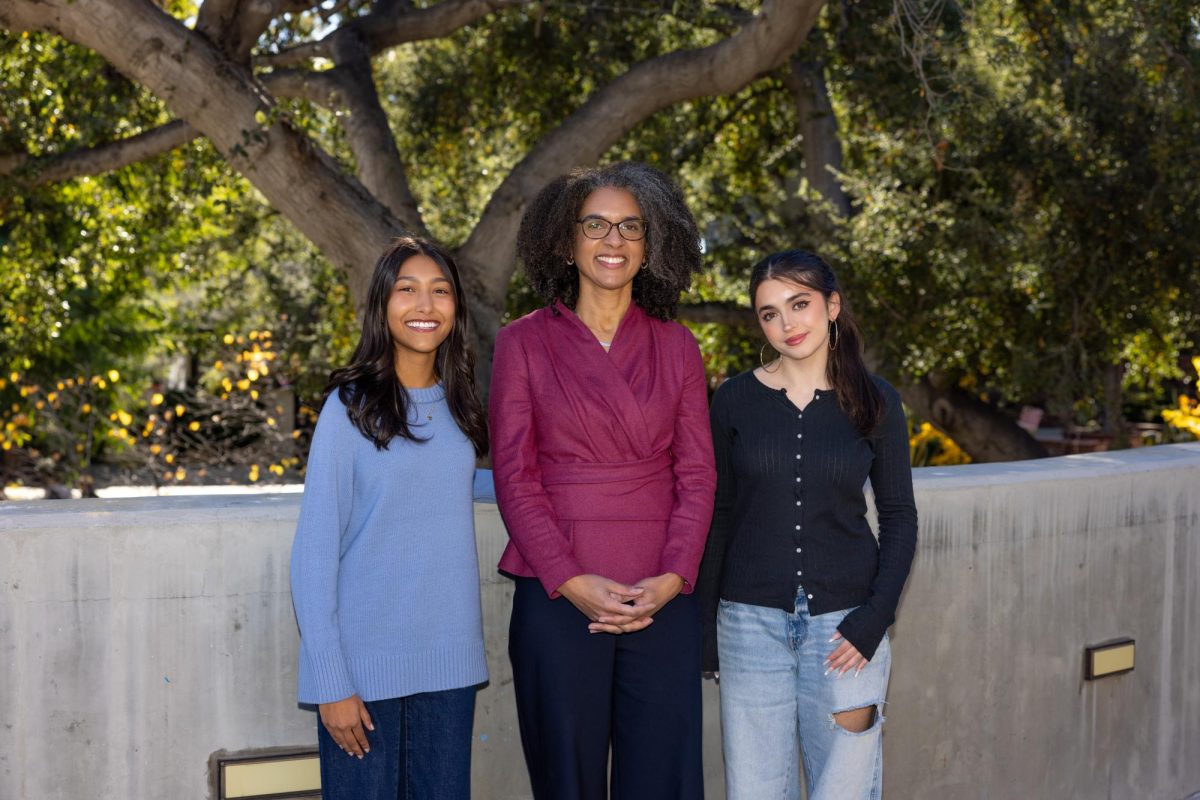

Following the joint affinity group meeting, History teacher Samuel Anderson; Spanish teacher, 11th Grade Coordinator and Iranian Culture Club advisor Cynthia García-Macedonio; History teacher and JSU advisor Avi McClelland-Cohen; and College Counselor and 11/12 Grade Dean Garine Zetlian, who advises the Armenian Culture Club and Middle Eastern Affinity Group, communicated the affinity groups’ request for a Middle Eastern studies class to the administration.

Earlier this year, Anderson, who specializes in Middle Eastern and African studies, proposed a history elective on the Middle East to Upper School Director José Melgoza, Dean of Faculty Harvey Johnson and the Upper School Department Chairs. However, the proposal was rejected, and the course is not listed in the 2025-2026 Upper School Course of Study.

“Ultimately, the administration decided it wasn’t the right year for that, mostly because of staffing things,” explained History Department Chair Kristen Osborne-Bartucca. “It’s hard. We’re a small department… I wish we could cover everything.”

“I don’t fully understand the way things work,” Anderson commented. “I think it’s scheduling. I mean, honestly, I feel like it would be a lot for me as a teacher to pull together in class, so I don’t mind having a little more time to think about it and to put something together that I think would really work well. So that’s, I think, also part of it: I’m eager to do it but also aware that I want to do it right.”

Director of PolyGlobal Rick Caragher shared that the current Global Scholars cohort spent three weeks this past fall studying aspects of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. While PolyGlobal has held evening events about the Middle East, the program has not organized an evening event about the conflict since Oct. 7, 2023.

Anderson, García-Macedonio, McClelland-Cohen and Zetlian have met several times to discuss how to continue the affinity groups’ work, considering the possibility of organizing a schoolwide event about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. However, the group has faced various obstacles—from funding to internal disagreements—in trying to put together the event.

In an email response, McClelland-Cohen shared, “We’re still hoping one might happen, but for an event like this we need to find some institutional support (and funding!) and haven’t been able to make it happen yet.”

“With the Middle East, everything is charged because the enmity has lasted so long,” said Zetlian. “Hence, the disagreements. Do we bring so-and-so to speak? What are they going to say? Are they going to be misunderstood? Are students going to react in a harsh way? We always end up with the questions and not an agreement on what to do.”

Of course, it is important to ensure that we approach complex issues such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in a sensitive and appropriate manner. It becomes worrisome, though, when these questions paralyze us from taking action and we develop an aversion to discussing contentious subject matter, as seen in the Poly community.

“Teachers are afraid of getting into controversial topics,” McClelland-Cohen observed. “I think a lot of teachers don’t know how students will react, don’t feel prepared to teach controversial content in a sensitive way and are unsure what support they will receive if there’s backlash.”

“It is honestly quite sad and disappointing that schools like Poly are scared to teach their students about Middle Eastern culture,” Parsa expressed. “Our culture is beautiful and rich, and it is a shame that it is so hard for us to share that with our classmates.”

At the time of 9/11, Zetlian was teaching the World Cultures class on the Middle East.

“We were talking about what was going on on a daily basis,” Zetlian recounted. “The newspaper was our textbook.”

By looking at how Poly met the moment in times of crisis and uncertainty in the past, we can find a path forward in the present. We can reframe our perspective on controversy, viewing it not as a reason to grow silent, but as an opportunity for intellectual and personal growth.

Poly’s Vision and Mission states, “We envision a community of students, inspired by transformative teaching, who will contribute profoundly to the world as intellectual leaders.” In order to fully actualize this vision, it is essential that our education at Poly helps us develop the tools we need to participate in and learn from controversial events. Such conversations may be uncomfortable—but an uncomfortable discussion is better than no discussion at all.

Our time at Poly must prepare us to navigate the contentious, complicated world that we live in. After all, isn’t that what education is all about?