As we approach the end of the first quarter, it seems that tests continue to be the “go-to” way to gauge student knowledge. As the assessment calendar begins to fill up with exams, however, we see far fewer projects and presentations There are several reasons why tests are more popular: they are easier to grade and create, provide an easy way to see who knows what information and are clear benchmarks against other students’ performance. According to a Concordia University article on testing, “Multiple-choice tests and other types of standardized exams can be graded quickly and easily, often by automated systems.” Even without Scantrons, teachers can often refer to answer keys when grading exams – a streamlined process unlike that of evaluating an in-depth project.

Even so, while tests might be the more traditional mode of assessment, they create many obstacles that hinder students’ learning.

Firstly, tests tend to rely too much on memorization. Since students often cram for tests by hurriedly memorizing fact after fact, they heavily rely on short-term memory for the next 12 hours. As a result, most of the information fades quickly after the test.

Oxford Learning explains the idea well: “So while cramming can help you rock that test tomorrow morning, when it comes to long-term remembering, it’s utterly useless. That’s because in school, learning is incremental. Students need to remember—and understand—the material they study, because lessons tend to build upon what was taught previously.”

Freshman Madison Gaspard shared, “I almost never recall any of the information after the test….There are sixth-grade history tests that I remember everything from, but I couldn’t tell you a single thing about ionic bonds.”

Additionally, tests themselves elicit a narrow skill set, confined to memory recall, reading comprehension and pattern recognition. They rarely measure inquisitive research, innovation or collaboration, which are imperative competencies for students as they move on to navigating challenges in their professional careers and relationships. This is particularly true for STEM courses, which rely more heavily on tests than project-based assignments; English classes often feature essays and writing assessments, which tend to be more nuanced than a fact-based exam.

Whereas tests are often a “one and done” form of assessment, Gaspard expressed that projects provide her with skills that are much more important to her for her future career. When asked about the skill set she gains, she said, “Definitely extemporaneous speaking. In life, in a business setting, I’m more likely going to need to be giving a PowerPoint presentation or providing a speech than being sat down taking a test.”

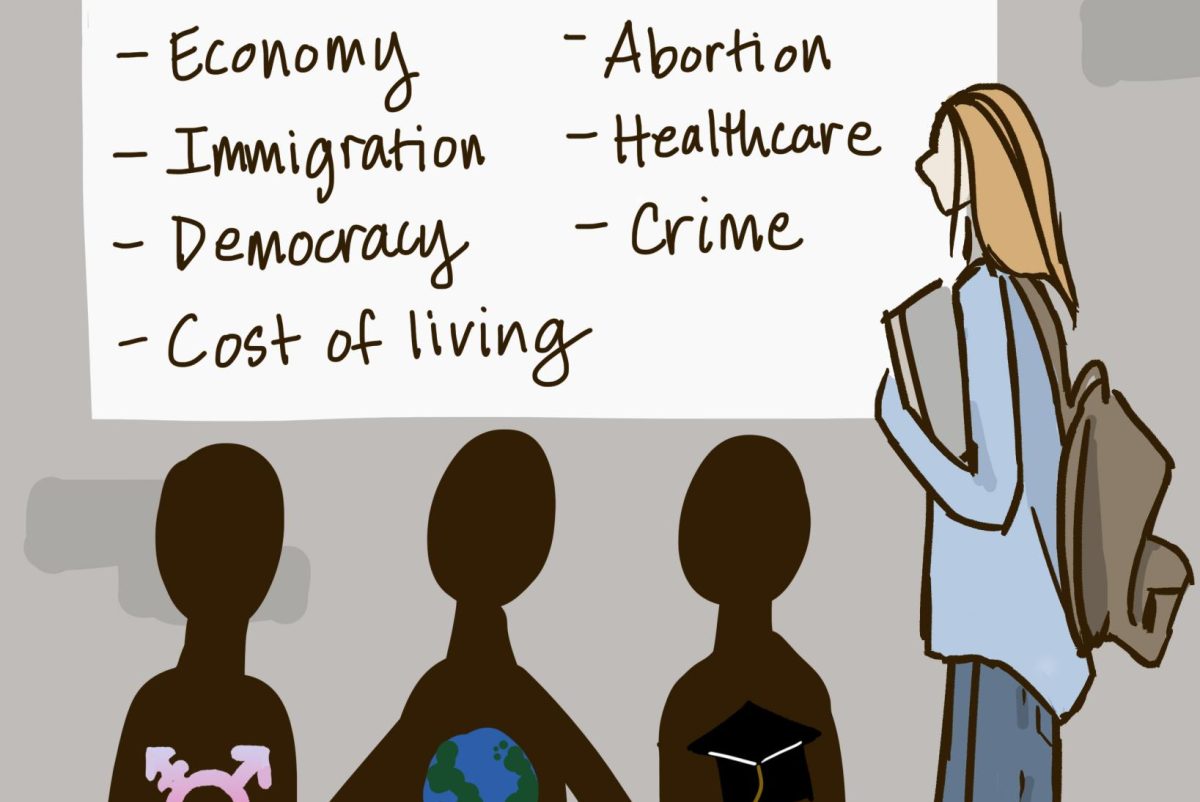

Projects and presentations, or other forms of assessment that force students to explore topics in-depth and apply concepts, are far more beneficial. This type of assessment helps reinforce knowledge by requiring critical thinking and creativity, as students are forced to assess the reliability of certain sources and detect their biases to construct useful and informative visuals.

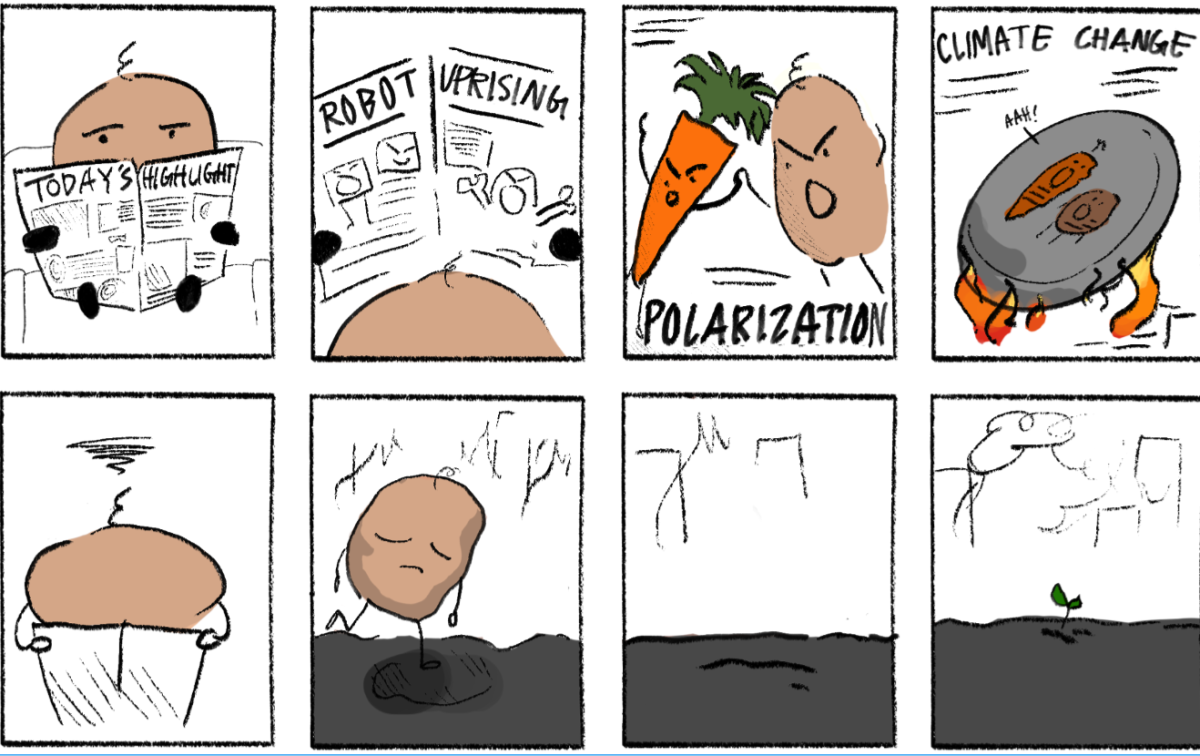

Collaborative work is a significant advantage of project-based learning. Although it can be challenging for teachers to properly assess individual contributions to a group assignment, communication and teamwork are essential and constantly relevant in both academic and professional settings. When working on group projects, it is common for students to encounter disagreements. Nonetheless, these disagreements present an opportunity for students to navigate differing perspectives Students learn how to behave in a communal setting, be assertive without being dominating, and be receptive to others’ ideas without being too passive – essential expertise for effective leadership.

Overall, it is not realistic to completely eradicate tests from the curriculum, as they do serve an important purpose. However, it is time that teachers include a diversity of assessments in their classrooms. For instance, classes that typically include one or two projects throughout the entire year should increase that number to three or four. And, if a teacher decides to prioritize tests, they should be designed in a way that encourages longevity of knowledge. The ninth-grade Integrated Science class achieves this by allowing students to re-assess topics until they reach proficiency – encouraging deep understanding over last-minute cramming and rote memorization. It’s time to let go of tests and their rigidity so we can equip students with the skills and knowledge they need as budding intellectuals.