The first time I ever put on Schmopium, a style of clothing that emphasizes darkness and moodiness, I was 14 years old. It was at my friend Alejandro Kohn Rabassa’s house, and when he told me that he made the pants himself, I was struck with a sense of awe. Looking back, I think I was jealous that I hadn’t figured out my own sense of fashion. That jealousy and awe, but more importantly, Kohn Rabassa’s individualism, would not have existed if it weren’t for the fast fashion industry.

Fast fashion extends far beyond popular brands like Zara, Shein and H&M. It includes smaller companies, and often individuals, looking to explore their fashion interests and express themselves. These individuals encompass consumers looking for trendy and affordable clothing as well as producers looking to establish their own. They turn to fast fashion as they can explore their sense of style through an industry that encourages quick, cheap and low-risk production.

The only reason this individuality can exist is because of the affordability and accessibility made possible by overseas factories in countries like China, Pakistan and India. Fashion designers typically have two options for producing their clothes: they can buy their fabric in the United States and make the clothes themselves, or they can send their designs to factories abroad.

Kohn Rabassa shared, “Factories in the U.S. exist, but they are less accessible. They are harder to come by… and they’re more expensive.” Kohn Rabassa and other individual fashion designers prefer to send their designs to countries like China. He explained, “You are bound to screw something up if you make clothing in-house and you often have to buy way more fabric than you need.”

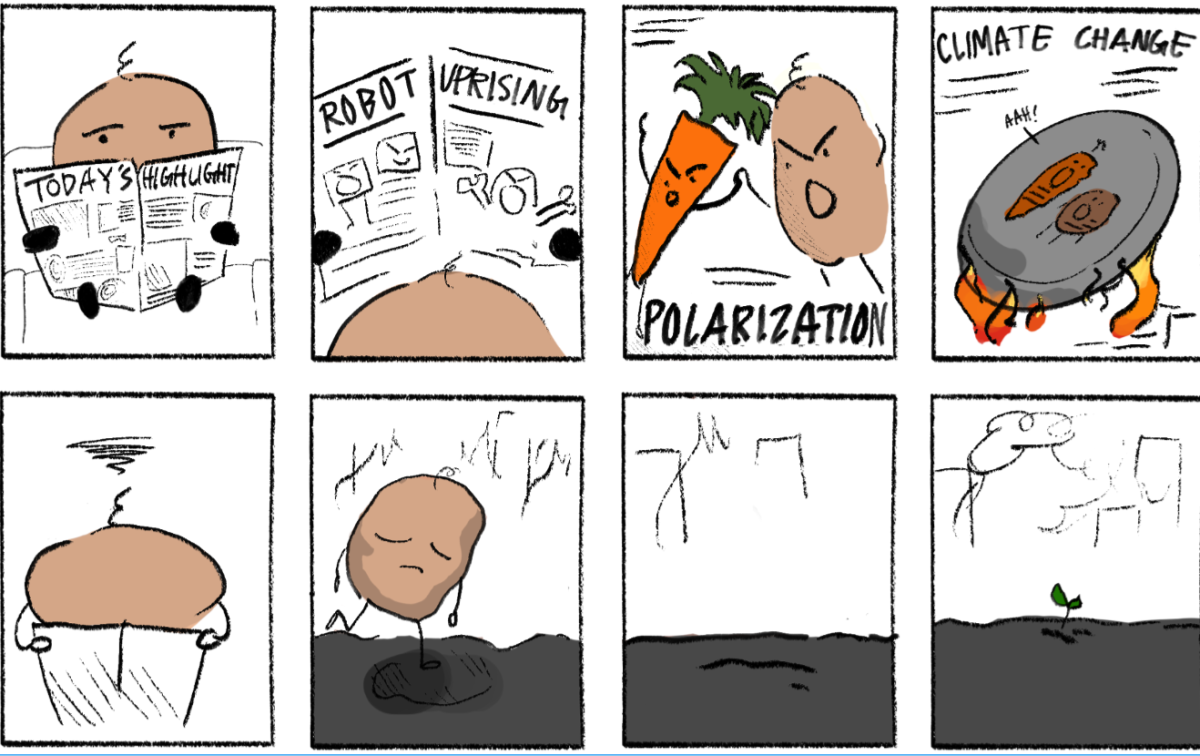

Critiques of fast fashion frequently highlight the low wages and poor working conditions in overseas factories, which is an understandable concern. However, our world so heavily revolves around the practice of fast fashion and fast-paced production that it would be impractical to imagine an alternative. First off, workers willing to work in legal factories would lose their jobs. Then, underground labor markets would popularize because even though legal factories would be banned, illegal ones wouldn’t be. Demand for labor and foreign investment in overseas labor would persist; therefore, opportunists would take advantage of this demand to create illegal job markets. Factory workers without jobs would easily take these illegal job offers out of desperation, trapping themselves in a predicament of choosing between more dangerous, lower-paying work and no money at all.

Human rights abuses would persist because these underground workplaces would remain hidden from the outside world, with factory owners afraid to let the public lay its eyes upon an illegal sweatshop. In stark contrast, Kohn Rabassa states that the factory he works with has accountability.

“Erim Yao from Guangzhou, China is my agent,” he said, referring to the person who represents the factory he works with. “I can put a face to the operation.” Right now, there is a semblance of transparency within these factories; It’s not as if they hide child labor behind doors closed to the public. The situation isn’t ideal, but it’s better than the alternative.

A world without fast fashion is a world without economic opportunity and artistic expression. Maybe the whole idea of capitalism is flawed; these workers shouldn’t have to work for such little compensation, but there isn’t a better alternative for them other than tearing down the economic system our world operates on. For now, we should appreciate the expression and economic growth fast fashion allows for and remember that working conditions can only get better with increased foreign investment in these factories.