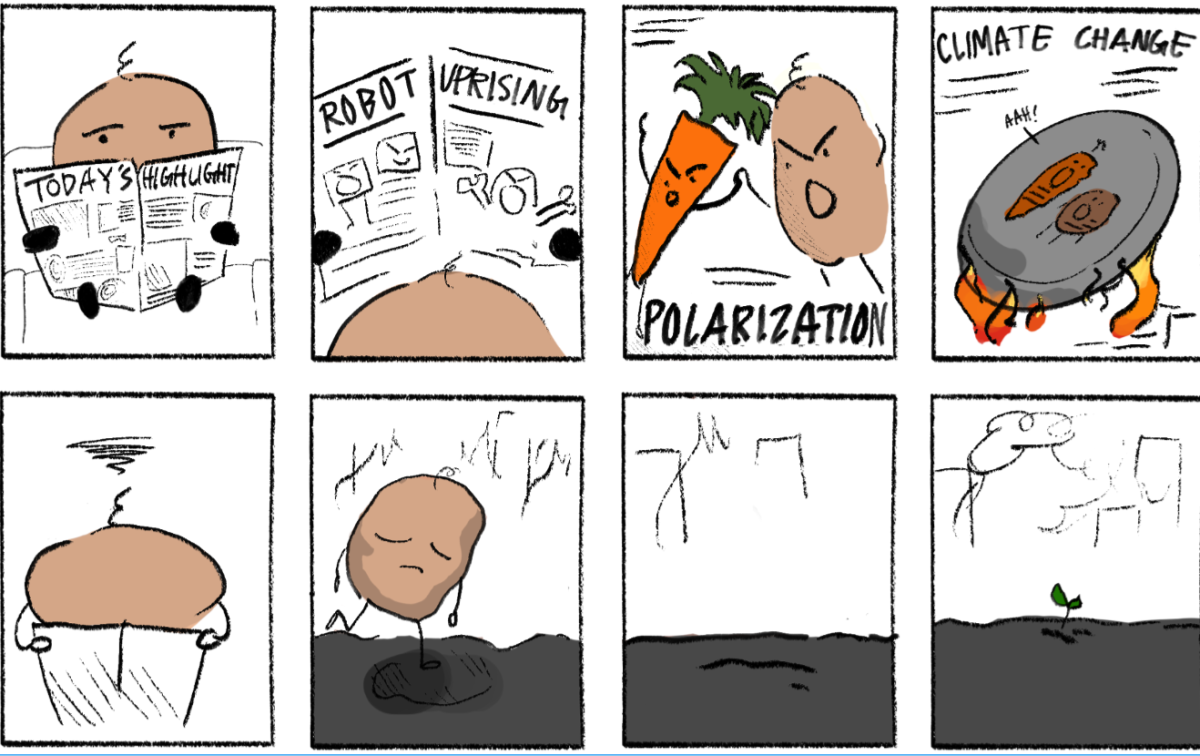

Social media’s revolving door of microtrends has birthed a recent obsession with the “sad girl” aesthetic and all things “tragically beautiful,” flooding For You pages with montages of teary-eyed actresses set to the wistful melodies of Lana Del Rey. However, this infatuation with melancholy extends beyond yet another fleeting aesthetic. In romanticizing depression, bipolar disorder and a host of other psychological afflictions — sometimes even framing them as desirable characteristics — platforms like TikTok and Instagram have significantly altered our generational outlook on mental illness.

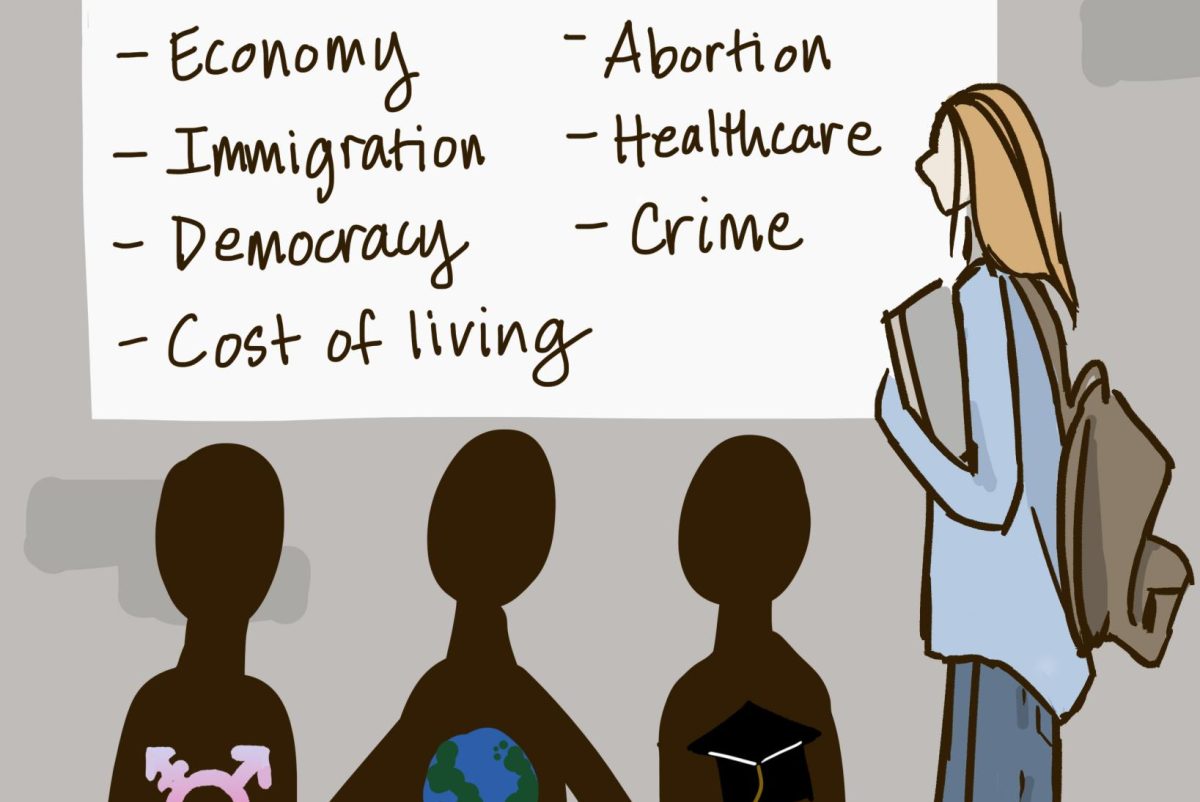

While Western society has made great strides in ridding mental health of its taboo connotation, one mustn’t conflate destigmatization with romanticization. As the topic of mental health saturates modern discussions and permeates social media, our generation’s hyper-awareness has almost desensitized us to mental illness, detracting from its gravity. Of course, receiving proper information regarding mental health is paramount. Instead, the problem lies in the dissemination of misinformation through social media as well as the implicit assumption that casually throwing around terminology is a viable mode of discourse on mental health.

When asked about social media’s role in portraying mental health, Upper School Counselor Andrea Fleetham remarked, “I think there’s been some glamorizing, which is two-fold because that means people are open to talking about it, but it also means that there’s a lot of inaccurate information out there about mental health and mental illness.”

Fleetham explained the possible harms of inaccuratly representing mental health in media, in which clinical conditions are often distorted to seem less grave: “It also feeds into stigma in a certain way. If everyone has anxiety, then if you have legitimate, clinical anxiety, people won’t take you seriously because we use it so casually now. It kind of belittles and diminishes the clinical reality.”

In tandem with its misrepresentation of these psychological conditions, with vague and incongruous definitions of what it means to be depressed or have a mental breakdown, social media even goes so far to valorize mental illness. Apps often portray anxiety and depression as mere quirks — mysterious and intriguing traits that add to the allure of the individual. Specifically, our generation has grown transfixed with this notion of female sorrow, the “sad girl” archetype. This aestheticization of female pain distilled into a caricatured sad girl is often seen as a “relatable” portrayal, but it contorts genuine pain into a glamorized illusion.

The sad girl takes generational sadness and beautifies it with cable knit sweaters and blankets it in dreamy, wistful soundscapes. She makes us see her sadness in all its glory without any real appeal for change. She lives a stagnant life with the “sad girl starter pack” playing in the background in perpetuity. Yes, the sadness is visible through hashtags, but it is not in any way subversive; rather than challenging the systems that oppress her, the sad girl romanticizes her suffering and makes us want to as well.

Thus, as we caption our posts and scroll through media platforms, it’s essential that we question the validity of the information we digest. Romanticization may sound more appealing than reality, but glorifying mental illness clearly has the potential to augment stigma rather than reverse it. It’s essential to acknowledge mental health as a complex and severe issue, and the pursuit of understanding and support should be grounded in empathy, truth and a genuine commitment to change rather than in the allure of a particular aesthetic.