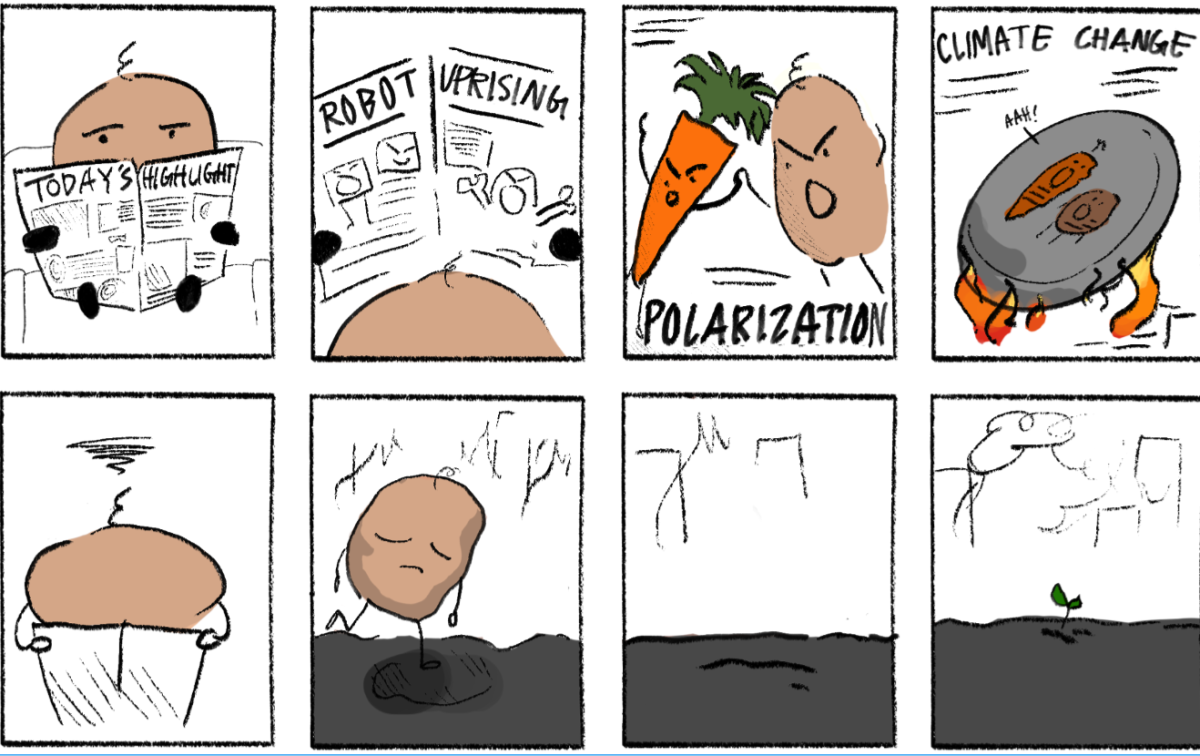

Thirty years ago, high schoolers went to school, played sports, did their homework and went to sleep; this cycle repeated itself, and––for the most part––as long as you had good grades, were passionate about something and worked hard, you could expect to be a strong contender for admission to the university of your dreams.

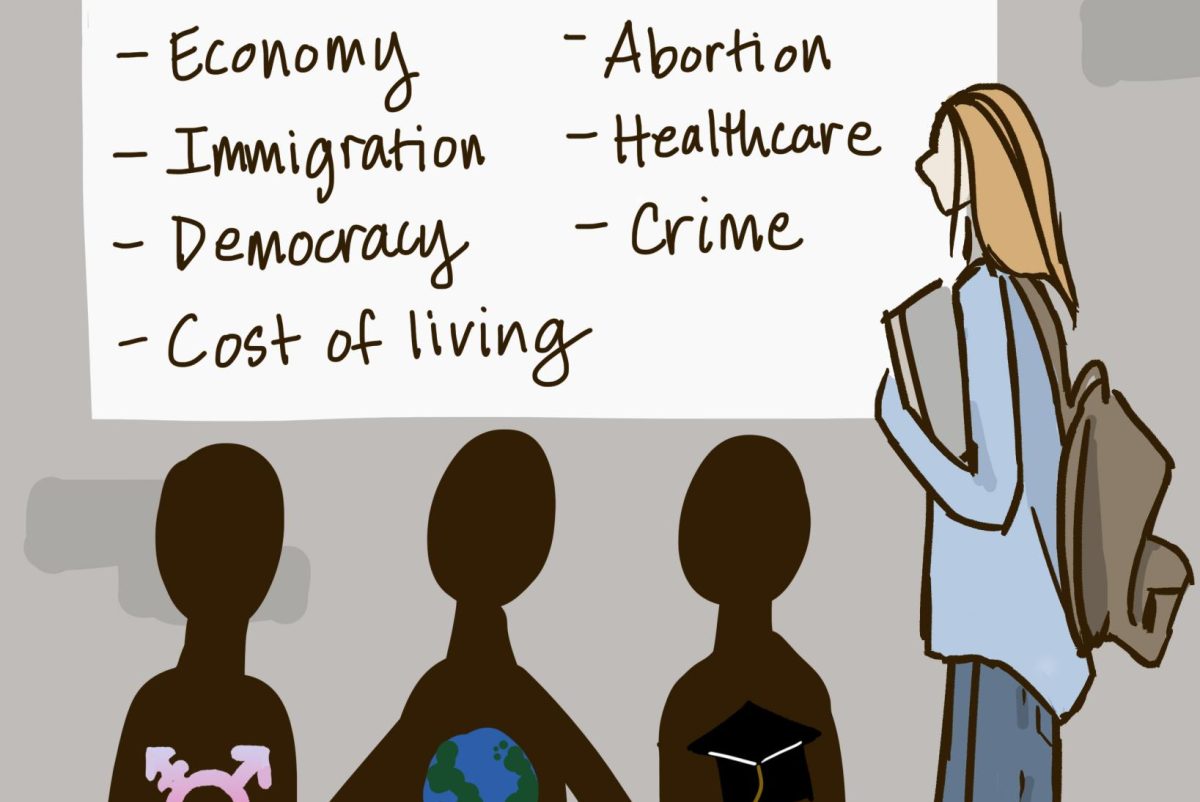

In the current status quo, that is no longer the case. Growing a passion has become less and less organic, as it has been mechanized into a strategy for getting into colleges. High school was once a time for experimentation; now, it feels like a four-year audition for college admissions.

The problem is that the college admissions system itself rewards those who can best optimize their time, energy and image with a dazzling acceptance letter. Over time, this optimization has become an unspoken requirement, reshaping what childhood, adolescence and learning are supposed to look like.

A study conducted by Dr. Rachel Rubin, founder and CEO of a college consulting firm called Spark Admissions, found that between 2021 and 2024, the number of applications to colleges surged by up to 57% at America’s top public universities, and acceptance rates have plummeted as a result of enrollment strategies becoming more selective. We can see this with private universities as well; for instance, NYU saw a record-breaking number of applicants to its class of 2029, receiving over 120,000 applications.

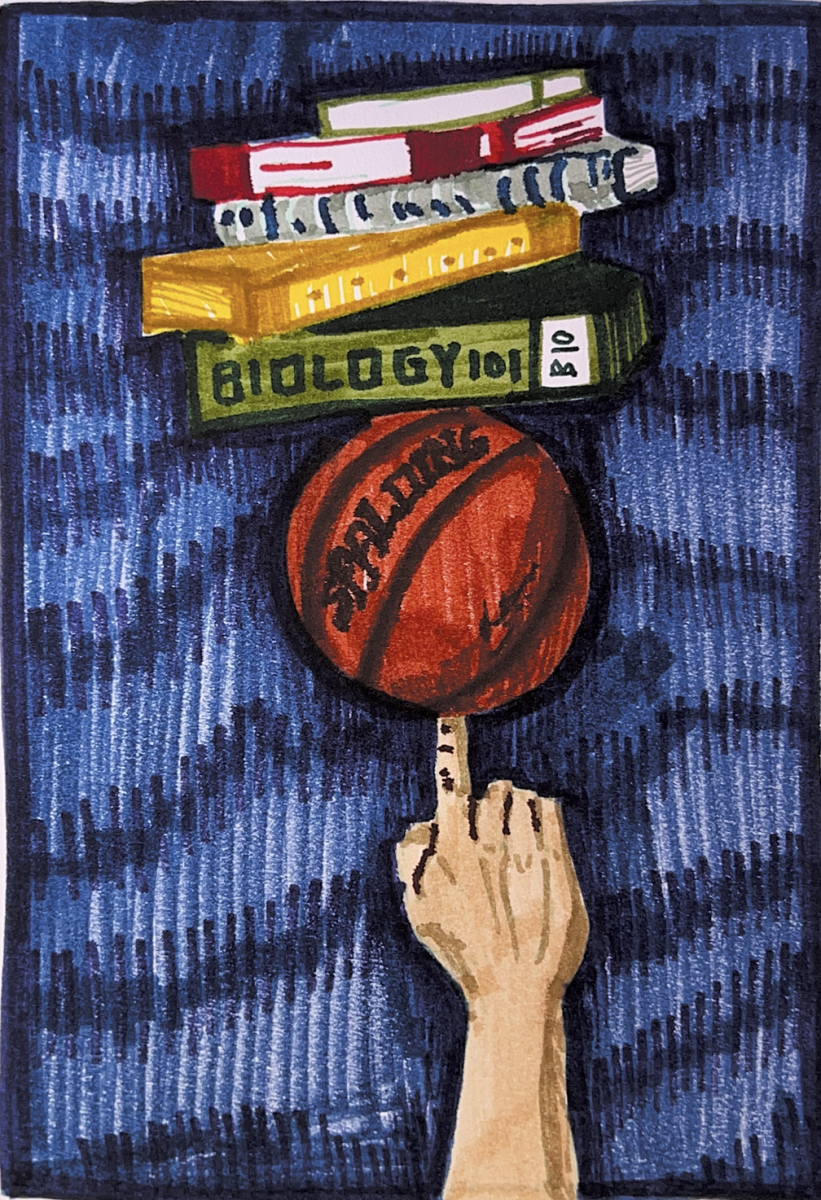

Students, in return, have learned to respond to this increased selectivity by stacking their schedules with countless APs and padding their resumes with more titles, more leadership roles, and more “passion projects” in hopes of improving their chances of admission. In doing so, they are pushed into implausible expectations: building nonprofits, conducting advanced research and taking on commitments that even many adults struggle to manage. Fulfilling these expectations deepens existing socioeconomic inequalities and ensures that this cycle of pressure continues for generations.

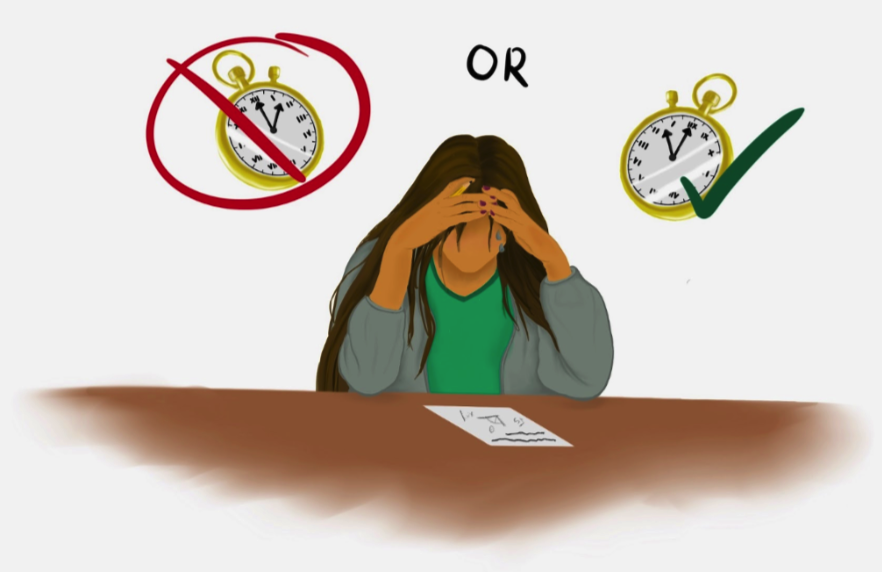

However, in the past, present and in the future, there have only ever been 24 hours in a day. With such lofty, unrealistic goals, students either cannot accomplish them, which leads to anxiety and the fear of missing out, or they complete them and only get three hours of sleep per night, which is also extremely unhealthy.

Director of College Counseling Mark Rasic commented, “The pressure for college admissions has always been high, but the stress level has only gone up over the years.”

These pressures stack on top of one another. The numbers shrink while the expectations balloon, creating an atmosphere where “enough” never feels attainable.

The more elaborate the “ideal” high schooler becomes, the fewer students can access that ideal. What emerges is a hierarchy not built on intellect or creativity but on resources, time and adult support networks, advantages that cannot be captured in a GPA or an application portal.

The deeper tragedy is what gets lost in this race for credentials: curiosity, risk-taking and joy. When schools and families treat college as the finish line, education becomes less about growth and more about presentation.

The admissions process prizes metrics over meaning. GPAs, standardized test scores and long lists of activities and awards tell colleges who can perform under pressure but not who can think independently or sustain interest over time.

Students internalize that message early. They take the hardest classes not because they want to master the material but because they want to signal that they can handle the grind. They volunteer to “show commitment,” not to serve. They conduct projects not because they enjoy what they are doing but because it “is the standard” and lets them check a box off on their resume.

Mr. Rasic said, “As the college counseling team, our goal is to figure out what the kid is like and find a school that works for them, not to match the kid with what the college wants.” Every “successful” student––that is, every student who gets into a top university––learns the same steps: take all available APs, run a club, collect community service hours, find a summer research program and maybe start a project with a glossy website.

It is a formula that promises safety but erases individuality. Even genuine passions get flattened into marketing narratives. Robotics becomes “engineering leadership,” and art becomes “creative expression for social change.” Everything must have an angle rather than doing something for the sake of loving it.

The pressure has consequences far beyond the classroom. The CDC reports that nearly 40 percent of high schoolers experience persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, and about one in five have seriously considered suicide. Pediatricians now call it a “national emergency.”

While the causes are complex, the academic arms race plays its part. When worth is measured in numbers, GPA, rank and admissions rate, students start to conflate performance with identity. Failure becomes existential.

This culture also deepens inequality. Wealthier families can afford independent counselors, paid summer programs and essay consultants. They can fund the extracurriculars that “signal leadership.” Meanwhile, students who spend their afternoons working jobs or caring for siblings often have less to show on paper. While colleges still value these activities, they may seem less superficially impressive than a student with the resources to found their own “nonprofit.”

What is most corrosive is how this environment stifles intellectual risk. Students avoid classes that might dent their grade point average, although they might be a subject of interest. They hesitate to explore new fields or attempt creative projects that might fail.

Instead of being authentic, their activities and interests are not what they enjoy but what they think colleges like to see.

Sophomore Aleah Norheim commented, “When I choose my classes or activities, it is 100% strategy for applications rather than genuine interest… College is about learning, and high school is about getting into college.”

Adolescence, which should be a time for exploration, becomes an era of risk management. A student who could have been a philosopher, artist or innovator learns instead to become a strategist.

A healthier system would not shame ambition but rather simply redefine success. It would reward depth over breadth and curiosity over compliance, thereby encouraging students to explore their interests when it is their best opportunity in life to do so.

In the path forward, we do not have to lower standards. We just have to make the standards realistic and positive.

We must allow ourselves to be learners again, not packages of a “perfect application.”