Code of Kings. Parents Pride. Chasing Artie. Chloe’s Dream. For those of you unfamiliar with the world of thoroughbred horse racing, those are names of racehorses. Dead racehorses. In the past two months, a dozen horses have died while running at Churchill Downs, home of the world famous Kentucky Derby. The spate of deaths has unsettled the racing world and called into question, not for the first time, whether or not horse racing should be continued in the future.

Although not as popular as it once was, horse racing still has an immense global audience. As many as 1.45 billion people watched or bet on horse racing in 2020, and each year, nearly $12 billion are bet at North American racetracks alone.

Having been to horse races myself, I can see why so many people are drawn to the sport. There’s the thrill of the starting bell, the uncontrolled roar of the crowd and the heart-stopping moment before the riders cross the finish line. And, of course, there’s the horses themselves. They are beautiful creatures, and seeing them in full flow, their muscles contorting in the morning sun, is a truly stunning experience. You cannot understand how incredibly fast the animals can run until you are standing just feet away from them, turning your head side to side as they blur by you.

Thoroughbred racehorses are perfect, the epitome of high-speed, high-endurance athletes. For hundreds of years, we have been fighting biological trends in order to breed horses to be faster, more agile and more spirited than before. We have molded their long, lean bodies, carved out their slender, twig-like legs and chiseled their strong, well-muscled shoulders. However, in the pursuit of the perfect racehorse, we have bred animals prone to devastating injuries.

Scott E. Palmer, the equine medical director of the New York State Gaming Commission, described the dangers of the sought-after body type: “Because they weigh about 1,100 pounds, the forces that are acting on their legs are really profound. When you get down into the lower part of the leg, there is literally skin and bones and tendons and blood vessels and nerves. If something breaks, the circulation of the area can be easily compromised by the injury.”

Moving at speeds of up to 44 miles per hour on slippery dirt surfaces, horses do get hurt. Their spindly legs crack. Their coke-bottle ankles snap. Injuries like these are often untreatable, so the most humane option is to euthanize the horse. We console ourselves, claiming that injuries are a part of sport.

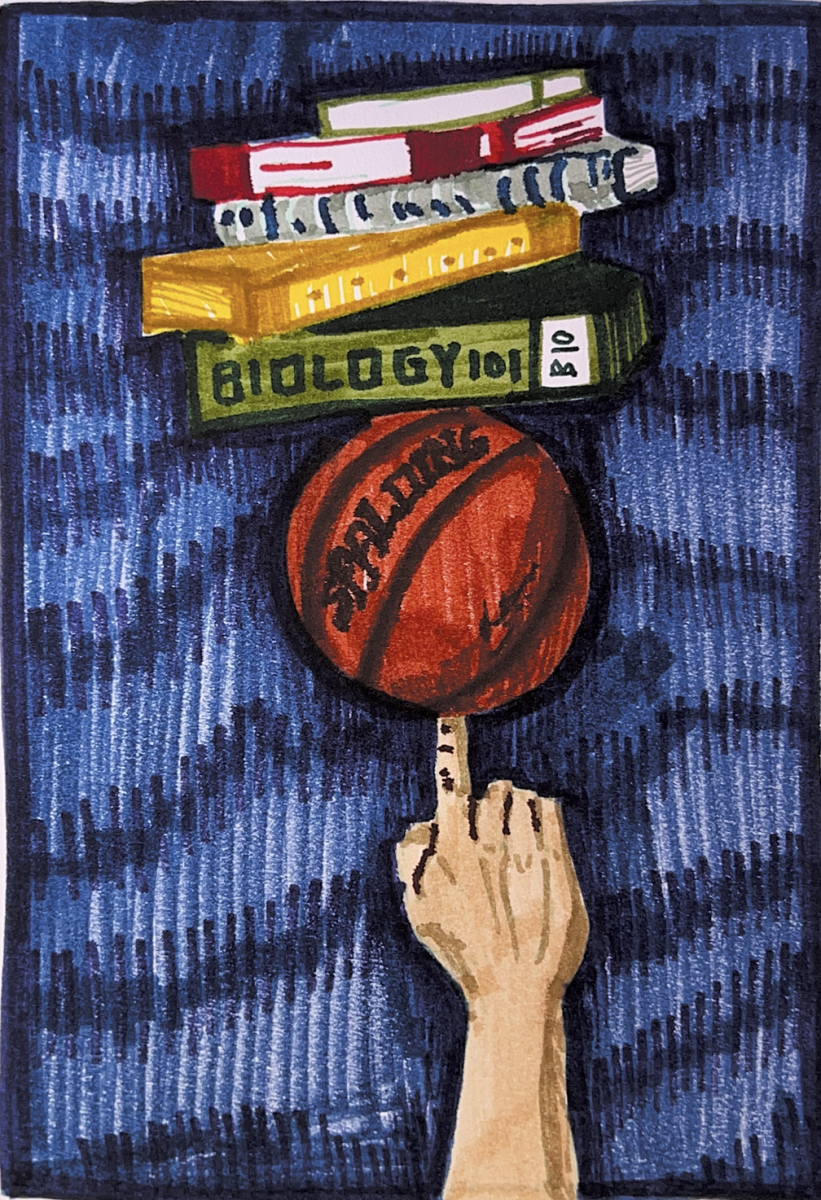

But who are we kidding? Yes, injuries can happen. They can happen in sports where the athletes choose to participate. They can happen in sports where the primary motivator is the love of the game, not the crack of the whip. Injuries can happen in sports where injured athletes receive pain-reducing shots, not life-ending ones. Euthanasia may be humane, but horse racing is not.

The recent spat of racehorse deaths and the barrage of negative media attention that has come along with them have forced racing executives into reluctant action. On May 30, the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority organized an emergency veterinary meeting to better understand the causes of the deaths and recommend a plan of action for the Churchill Downs racecourse. As I heard this, I should have been filled with some hope, but as I read the news of the convention, I couldn’t shake the feeling that we had been here before.

Back in 2019, in a period of just under six months, Santa Anita Park, the racetrack where I saw my first races, was responsible for the deaths of 30 thoroughbred horses. Even in a sport that averaged 10 horse deaths a week for the previous year, the spike in deaths created a shock wave. Trainers agonized, activists rallied and owners mourned. Racing executives scrambled to organize committees, which ended up banning whips and restricting the use of performance enhancing drugs. Still, the reforms, while surely a step in the right direction for the sport, allowed the culpable executives to deflect blame to the undeniably irresponsible, yet far less consequential actions of trainers and owners.

It is possible that the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority will enact effective changes that end the troubling trend currently threatening the sport of thoroughbred horse racing. But if the past has taught us anything, it probably won’t. For decades, racing officials have failed to stop the deaths that tarnish the sport they champion, and we have silently allowed them to do so.

But now, as 12 deaths crowd the headlines and 12 more 1,100-pound lives weigh on our consciences, we can no longer turn the other cheek. In the memory of the horses we have lost and for the sake of the horses whose lives are on the line we are sure to lose, let us change. And if we cannot, if the losses are not enough reason to fundamentally change the way thoroughbred racing is run, then we must ask ourselves whether or not horse racing is a sport that is worth continuing.