The Distinguished Alumni Award (DAA) honors alumni whose lives and careers reflect Poly’s commitment to intellect, integrity, service to others and respect for the world beyond. It is the school’s most prestigious alumni recognition.

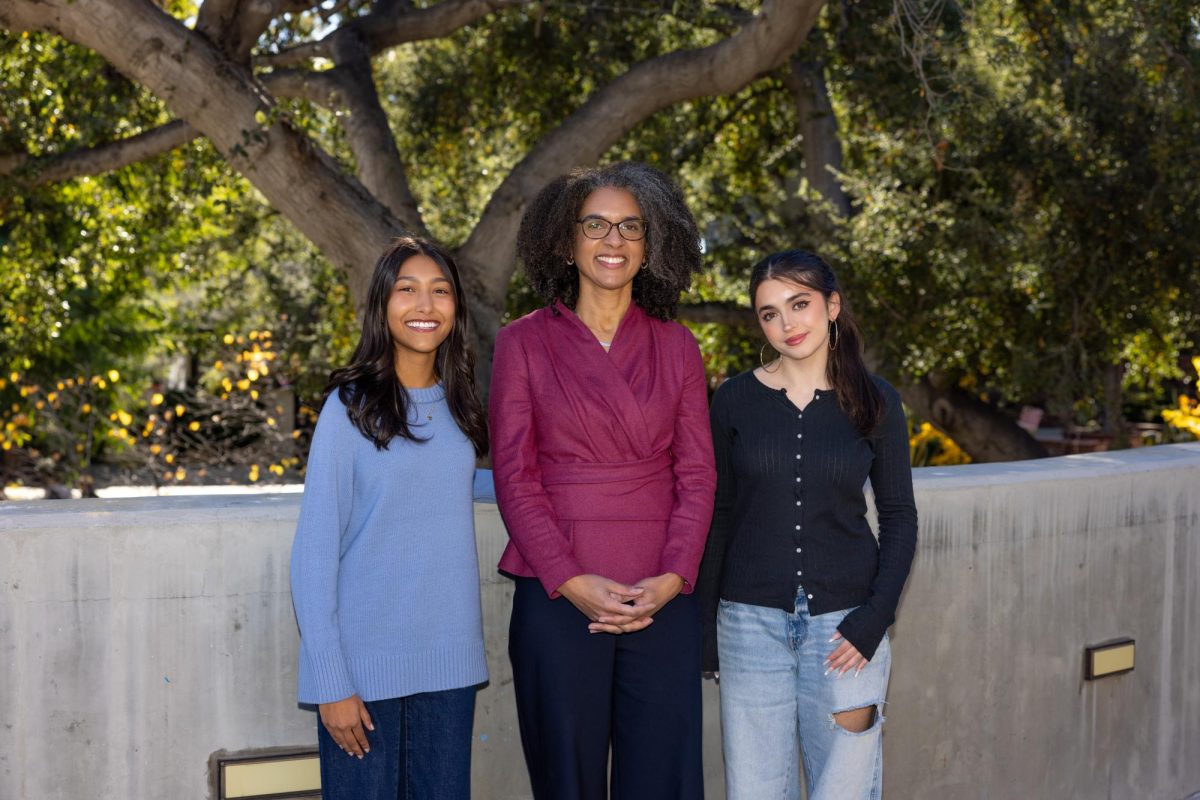

Justice Leondra R. Kruger ’93 was announced as Poly’s 2020 DAA recipient; however, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, her celebration was postponed to Thursday, Dec. 4, 2025, when we, as the editors-in-chief, had the opportunity to interview Kruger.

After graduating from Poly, Kruger attended Harvard College, where she wrote for The Harvard Crimson and was elected to the honors society Phi Beta Kappa. As a reporter, she covered several stories, including a hearing on Cambridge’s affirmative-action policy, the 1994 Senate race between the late Edward Kennedy and Mitt Romney, and a satirical travel guide to Pasadena.

She graduated with honors and attended Yale Law School. After earning her law degree, sheserved as a clerk to Judge David S. Tatel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit and to Justice John Paul Stevens of the U.S. Supreme Court.

From 2007 to 2013, she served in the Department as an Assistant to the Solicitor General and as Acting Deputy Solicitor General. The Solicitor General is often regarded as the “tenth justice” for their influence in the legal world, being the fourth-highest-ranking official in the Department of Justice. During her time in the Office of the Solicitor General, Kruger argued 12 cases in the United States Supreme Court on behalf of the federal government.

One case centered on the “ministerial exception” to employment-discrimination laws, which grants religious institutions the authority to decide who may serve in ministerial roles. The dispute arose after a teacher who was also an ordained minister was dismissed from the Lutheran school where she worked and sought to sue for disability-based discrimination. While serving in the solicitor general’s office, Justice Kruger argued that the teacher should be allowed to pursue her claim. The Supreme Court unanimously disagreed. In an opinion authored by Chief Justice John Roberts, the Court held that the ministerial exception applied, effectively barring the lawsuit.

In 2013 and in 2014, she received the Attorney General’s Award for Exceptional Service, the Department’s highest award for employee performance.

The Upper School assembly allowed students to hear Kruger’s firsthand experience of the legal system, and the two of us had the opportunity to hear from her in smaller groups throughout the day. During the official assembly, she discussed the importance of studying law, the anxieties of arguing before the Supreme Court, and the path to becoming a judge.

Much of the conversation was grounded in Kruger’s time at Poly. When asked how her high school days influenced her career, she emphasized her experience in high school debate. She shared that, contrary to the idea that lawyers are naturally outspoken, she wasn’t always confident and learned to develop her voice over time through Poly’s debate team––an anecdote that hopefully encouraged the softer-spoken members of the audience that being assertive from birth isn’t a prerequisite for a successful legal career.

While she first discovered public speaking through debate, Kruger has long enjoyed sharing her opinions in writing. A former editor-in-chief of The Paw Print, she recalled how she spent her days writing, whether for herself or right here in this very newspaper. The detail reminded us that the skills we develop through student publications extend well beyond the Upper School campus. I, Filiz, have always loved writing––creative pieces, opinion essays, journal entries––but I’ve always been told that few sustainable careers exist for “writers.” I was excited to see Kruger’s love of writing prominently featured in her current job.

In fact, Kruger’s life at Poly somewhat mirrors an average day in her current position. Debunking another lawyer stereotype––the action-taking interlocutor portrayed in shows like Suits and Scandal, Kruger reflected that her daily responsibilities as a lawyer primarily involved reading and writing. In other words, she spends most of her time at a desk, immersed in texts, rather than thinking on her feet in front of the bench. Her perspective offered a glimpse into the varying realities of a career in law, highlighting the diversity of experiences within a given field.

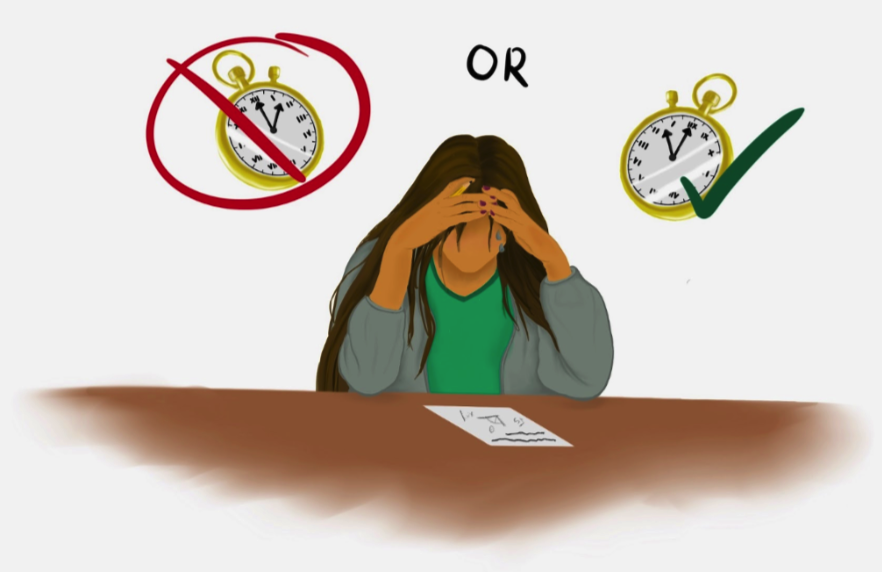

That is not to say that Kruger hasn’t compiled an impressive resume of courtroom arguments. While we’ve all felt an agonizing sense of dread before an important presentation, the pressure of arguing before the Supreme Court seems otherworldly. Kruger affirmed that the experience was undoubtedly stressful both physically and mentally, yet still described the opportunity as profoundly fulfilling. I’ve, Filiz, walked into many moot court rounds with a pit in my stomach, and it was reassuring to hear that even the most accomplished public speakers never quite shake that anxiety––that perhaps being nervous before a big event is just another indication that we care about our work.

Reflecting on her many academic and professional accomplishments, Kruger attributed her success to the many mentors and trailblazers who have guided her along the way, emphasizing that she could not have broken barriers on her own. She noted that her milestones, including becoming the first Black woman to serve as editor-in-chief of the Yale Law Journal and one of the youngest appointees to the California Supreme Court, were only possible because others had laid the groundwork ahead of her.

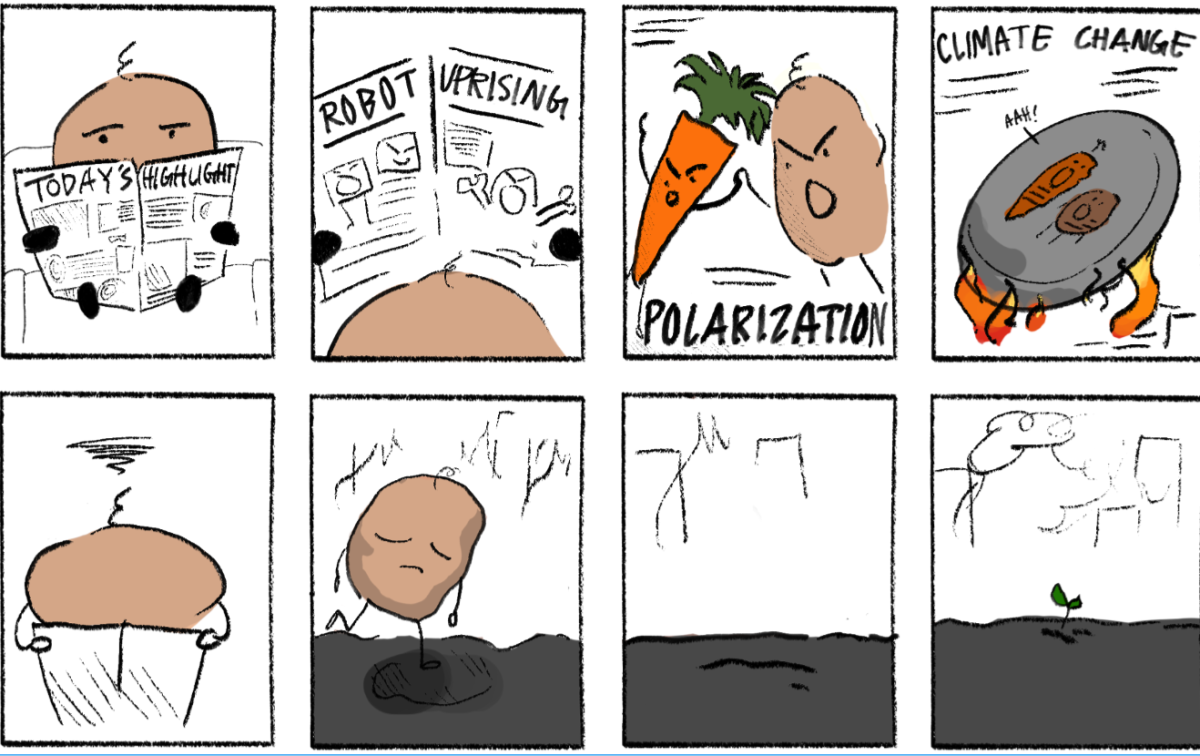

She expressed hope that she can provide the same support and encouragement to young Americans, especially those of color, as they continue the work of expanding representation. The sentiment was moving; often, as young global citizens and aspiring activists, we students feel the pressure to be the first—to do something unprecedented, to carry history on our backs. However, as Kruger reminded us, there is equal power in continuing, sustaining, and honoring the work that has already begun.

Near the end of the conversation, Kruger turned to the law itself, encouraging Poly students to engage with constitutional law as young citizens, even when it feels intimidating or opaque. She emphasized that the law should not live above us as a purely intellectual or ceremonial system, but as a living framework shaped through interpretation and participation.

When asked what advice she would offer to high school students today, Kruger spoke about living a life of service—something that she intentionally tries to practice in every aspect of her life. She advised students to pay attention to the work in front of them, without worrying too much about having everything figured out.

During a more intimate conversation with Poly’s student leaders of color, including members of the Black Student Union and the Student Leadership in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Council, Justice Kruger spoke with a candor that felt distinctly different from what I’d, Anya, observed in the larger assembly. For example, when a female student asked how she balances being the mother of two teenagers with the demands of her career, there was an immediate shift in her tone. She responded calmly yet sternly, noting that her equally successful husband is never asked the same question, while she faces it with striking regularity. Kruger explained that parenting in her family is a shared responsibility, with both partners equally involved, enabling her to achieve everything she does.

As she continued, I became acutely aware of how often women are expected to justify their ambition in ways that men are not, as well as how rarely that expectation is directly challenged. Kruger neither redirected the conversation nor softened her answer; she simply stated her reality and moved on. Walking away, I recognized a model of leadership that rejects false choices—showing that a woman, especially a woman of color, doesn’t have to choose between ambition and empathy, or justify either—and I promised myself to do the same.