Last month, while deciding which biology class to take next year, I considered several factors. Some were obvious, like the curriculum’s rigor and subject matter, but also important in my deliberations was the role of dissection. The course selection process prompted me to examine the ethics of dissections in biology classes.

Dissections have long been a common activity in high school biology classes because of the unique educational experience they offer. Tyler Saxton, who teaches AP Biology, explained, “I think it provides a benefit to have a physical, real-life example rather than a model that has been colorized to make it an optimal reference. A physical heart is, I think, a good thing to observe and see how it works.”

Biology teacher Dana Huley concurred, “It’s a hands-on activity. We spend time talking about the cardiovascular system, and this is an opportunity for them to actually hold something that would reflect what their heart would look like.”

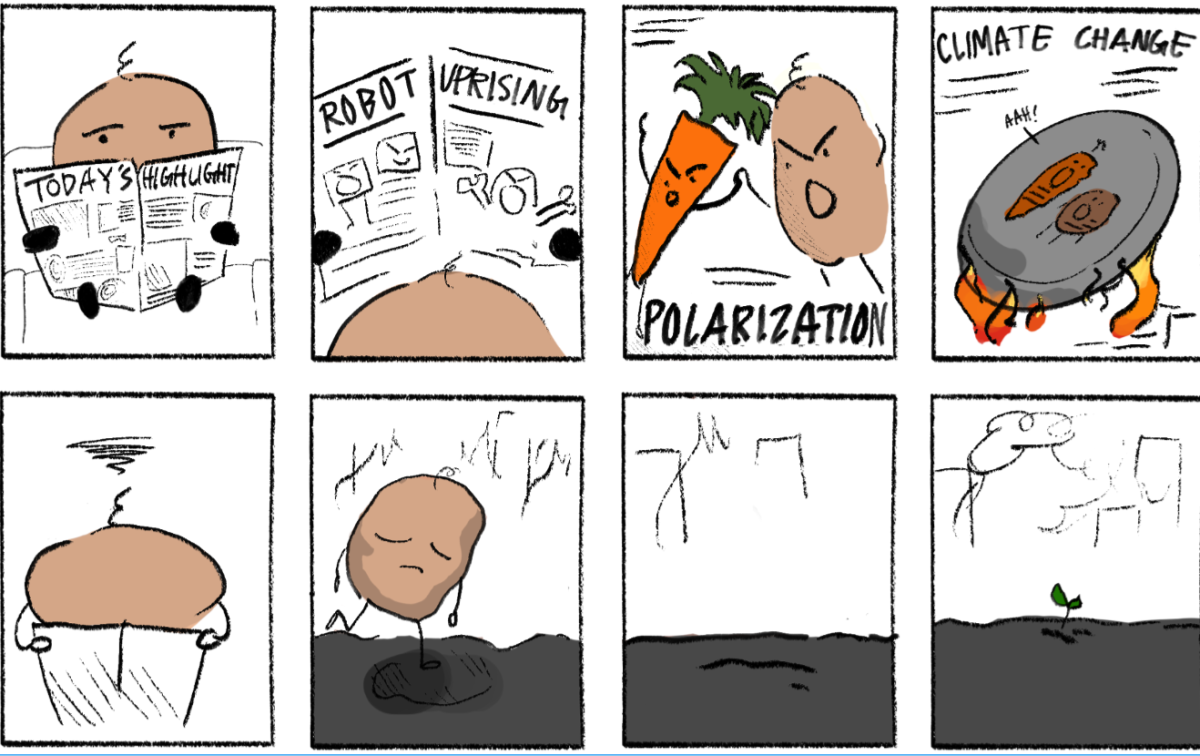

While the purpose of dissections is to advance scientific knowledge, ironically, science itself provides the main case against dissection. After all, it is through the study of biology that scientists have ascertained the extent of animal sentience. While the fact that animals have feelings may seem obvious to us, it was a foreign idea to scientists just two centuries ago. Yet, an overwhelming amount of scientific evidence acquired since then demonstrates that animals experience both positive and negative emotions just as we do. They also feel physical pain.

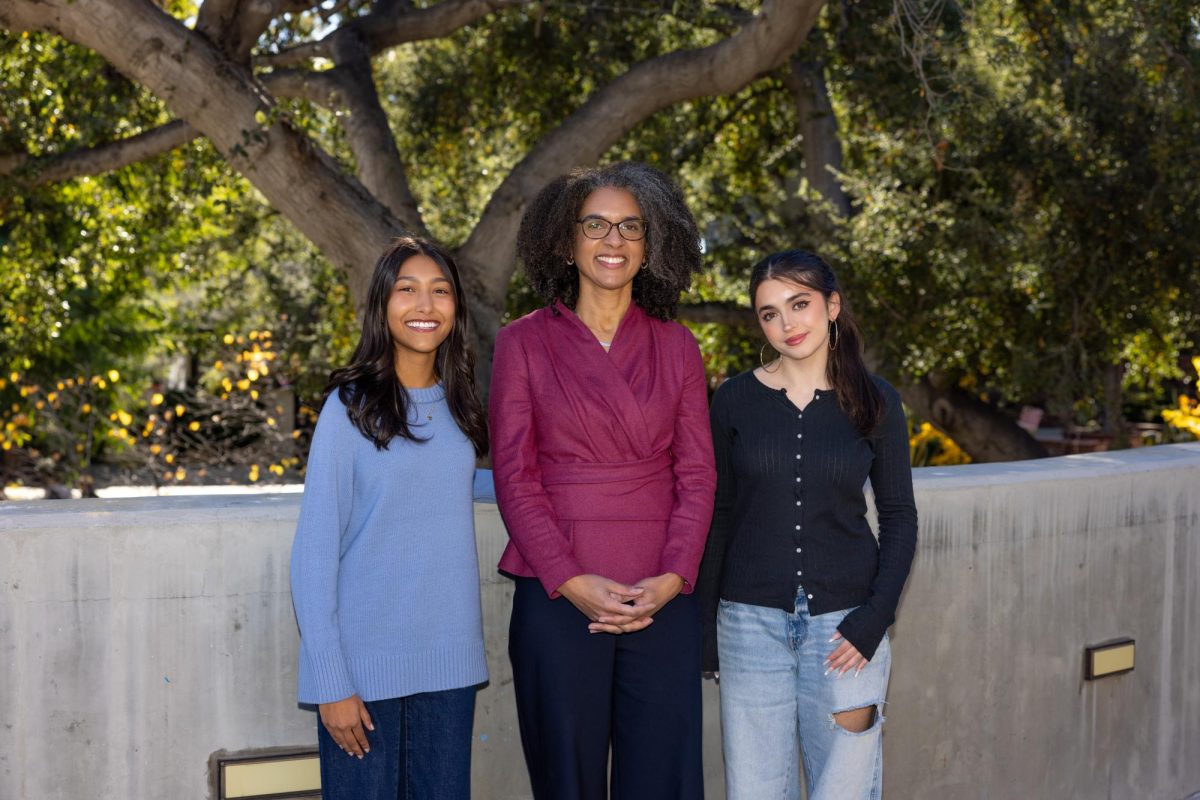

To examine the ethical case against dissection, I spoke to History Department Chair Kristen Osborne-Bartucca, who teaches the history elective Contemporary Ethical Issues. She compared dissection to factory farming.

She commented, “There is no difference in that we are viewing animals as something that is bred and raised and then used for our own consumption, and that our needs, whether it’s food or knowledge, are more important than the suffering of another creature.”

Some animals are raised and killed specifically for dissection; others are acquired for dissection after their deaths. Sometimes they died of natural causes; in other cases, though, they were killed in factory farms but are unsuitable to be sold and, thus, have no other use. In the latter situation, those who buy the animals for dissection are still monetarily supporting the industry that killed the animals, which provides that industry with the means to keep doing so.

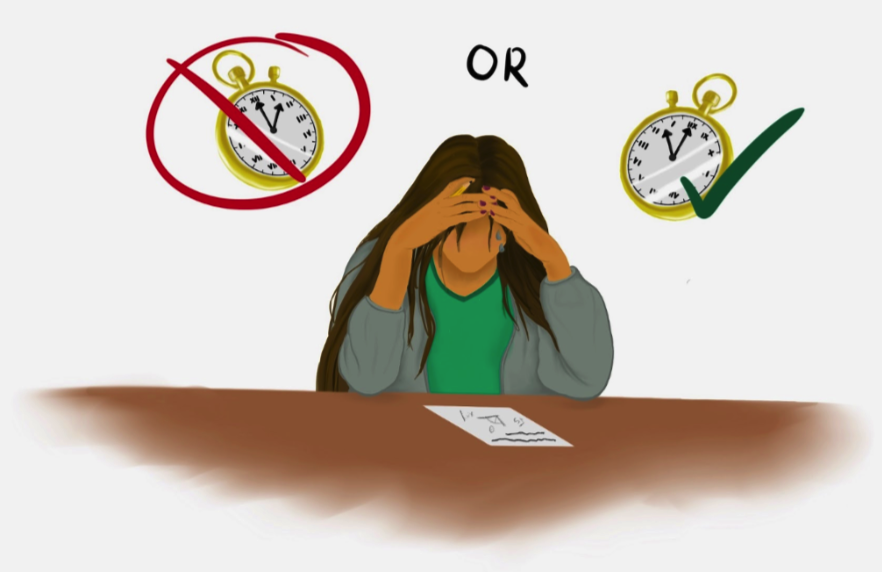

It is hard to justify dissections when recognizing their connection to animal suffering. It is harder still when one considers the many new alternatives to dissection. In recent years, a multitude of companies have created dissection kits with fake frogs and other animals, as well as virtual simulations.

Saxton, though, pointed out that the alternatives are not yet commensurate with real dissections. Animal hearts show what they actually look like; models only show what they’re supposed to look like. “It’s an optimal, not real-life example. It’s colorized to look blue and red. Whereas, the physical heart is normal, it doesn’t have any dye or anything like that, and so you can see how it works.”

Because of the shortcomings of these alternatives, the Science Department has chosen not to implement them. However, they have found another way to continue traditional dissections while also minimizing their negative impact. Huley explained, “We go to a local butcher shop where they already have the sheep hearts available. We’re not ordering them and then we get the sheep hearts. I ask them what they have on hand already, and I just buy what they already have.”

The eighth grade biology class follows a similar practice. Usually, stillborn pigs in factory farms are thrown away because there is no use for them. Poly buys them from a company that sells the fetal pigs for dissections instead.

Poly does a better job of sourcing their dissection materials than the traditional method of raising and killing animals specifically for dissection: it is certainly preferable to use already dead animals. Still, any instance in which animals are exploited for human gain is not without detrimental effects. Sometimes, the stillbirths are accidental; other times, they are a direct product of the industry’s blatant disregard for animal life. For example, when factory farms need to cut down on their animal populations, they sometimes kill pregnant pigs, resulting in the deaths of their unborn children as well. We vote with our dollars, and by buying the fetal pigs from factory farms, Poly is voting for the continuation of inhumane practices.

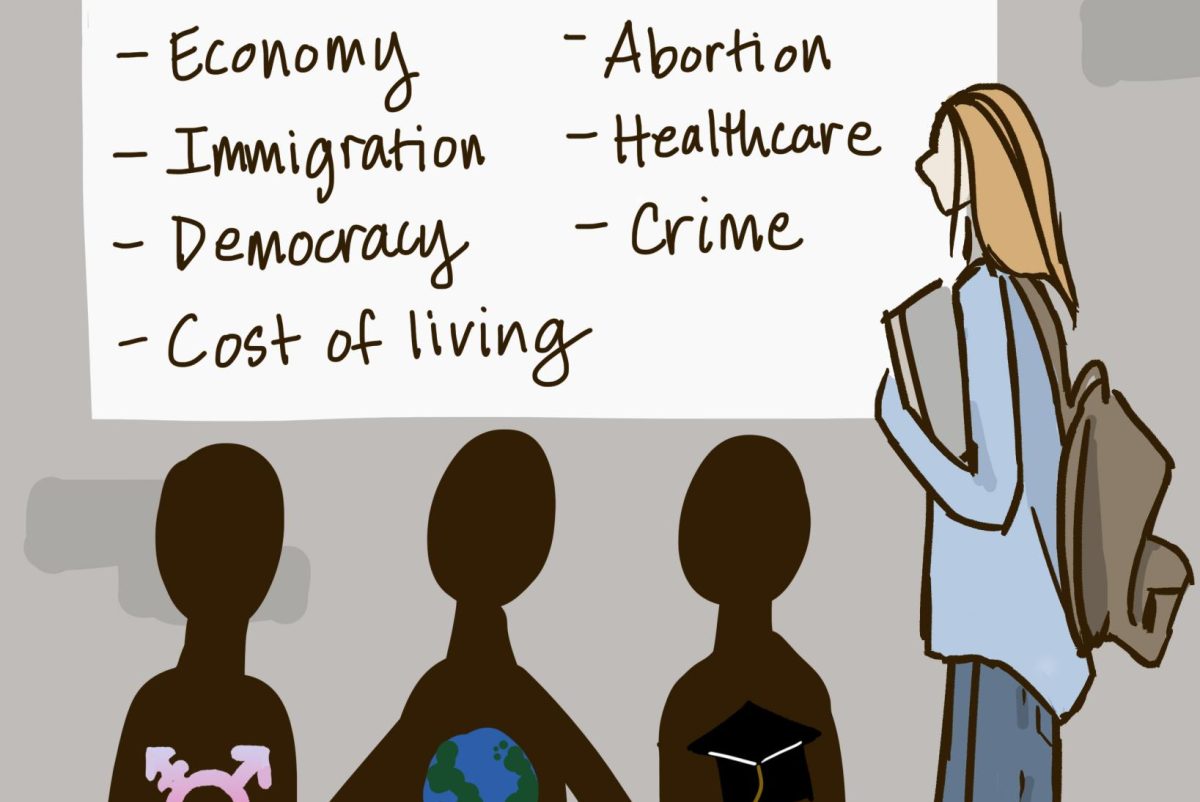

Ultimately, combating animal cruelty starts with education. Osborne-Bartucca observed, “Pretty much anyone who ever watches one of those movies about factory farming is like, ‘Oh, shoot. I’m probably going to stop eating meat.’ But no one wants to watch them because no one wants to stop.”

While it can be uncomfortable to confront animal cruelty, it is important to do so. Only then will we begin to see society’s treatment of animals change for the better.