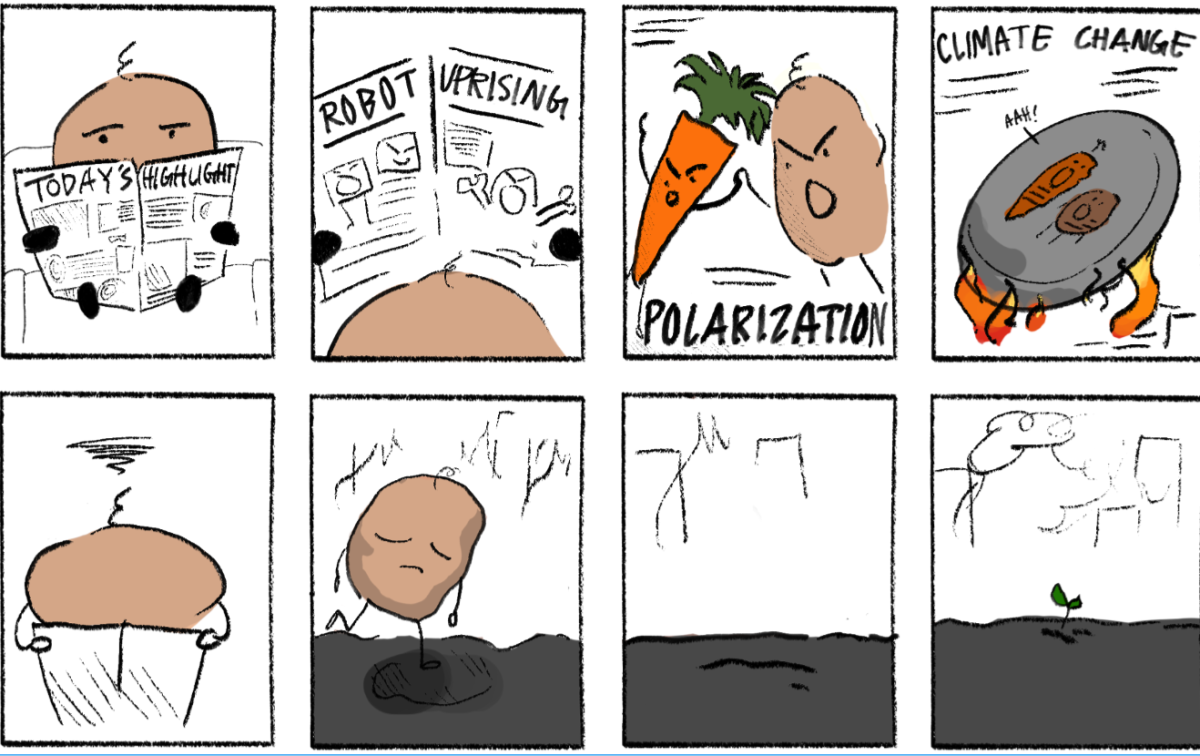

At the start of August, each Poly student receives their classes for the upcoming school year. Students rush to MyPoly to check if their friends are in their classes, what free periods they have and who their teachers are for the year. For many students, the teacher next to the course can feel more important than the course itself. That’s because, at Poly, the difference between two teachers for the same course can be the difference between an A and a B. The grading disparities between teachers at Poly across multiple departments could have an impact on students’ mental health and their future academic success, and Poly needs to address them.

One junior, Joseph Benitez, commented on his experience taking Modern World History in his sophomore year. “While I loved my teacher, I only know of one student who got an A in my sophomore year history class,” he explained. “I worked so hard for an A in that class, only to fall short. It was disheartening to put in so much effort and then watch half of the students in the other teacher’s class get an A for a quarter of the effort. It felt like my grade was determined not by my skill or the effort I put in, but by the teacher I was randomly assigned to at the start of the year.”

Joe’s experience is hardly unique. Students at Poly are aware of which teachers grade more leniently and which teachers are considered tough graders. This knowledge is so widespread that even before I entered high school, I told a friend in the same grade which English teacher I got, and he immediately responded, “You’re so lucky, you got the easiest one.”

Some variation between teachers’ grades is inevitable—with each class containing different students with different skill levels, it is unfair to expect completely equal grading between teachers each year. However, when there are significant differences in grade distribution every year and students understand which teachers are “easier” or “harder,” it is hard to attribute disparities to pure coincidence.

Getting “unlucky” by being assigned three or four tough-grading teachers could easily drop your GPA by a decimal point or two. While this drop in GPA is usually inconsequential for college admissions, it often puts more pressure on already stressed students who are worried about their GPA. It can also be incredibly demoralizing for students to put in extra effort to get a worse grade than they would’ve gotten with another teacher for half the effort. Given the impact on a student’s mental well-being, their grades should be determined by their skill and effort, not by luck.

However, it’s not just students who receive “harder” teachers that suffer; students with more lenient graders are harmed, too. If a student can get an A without putting in any effort because their teacher is an easy grader, they might be missing out on extra motivation to hone their skills. And they could get used to putting in minimal effort to get a decent grade, meaning if they get a more demanding teacher in the future, they could struggle even more. Because I was able to cruise to an A in my Sophomore and Freshman year history classes, I got used to lenient grading and lower expectations. When I took APUSH in my junior year, I received a C+ in my first quarter grade because the low effort would no longer cut it with the heightened expectations and more critical grading.

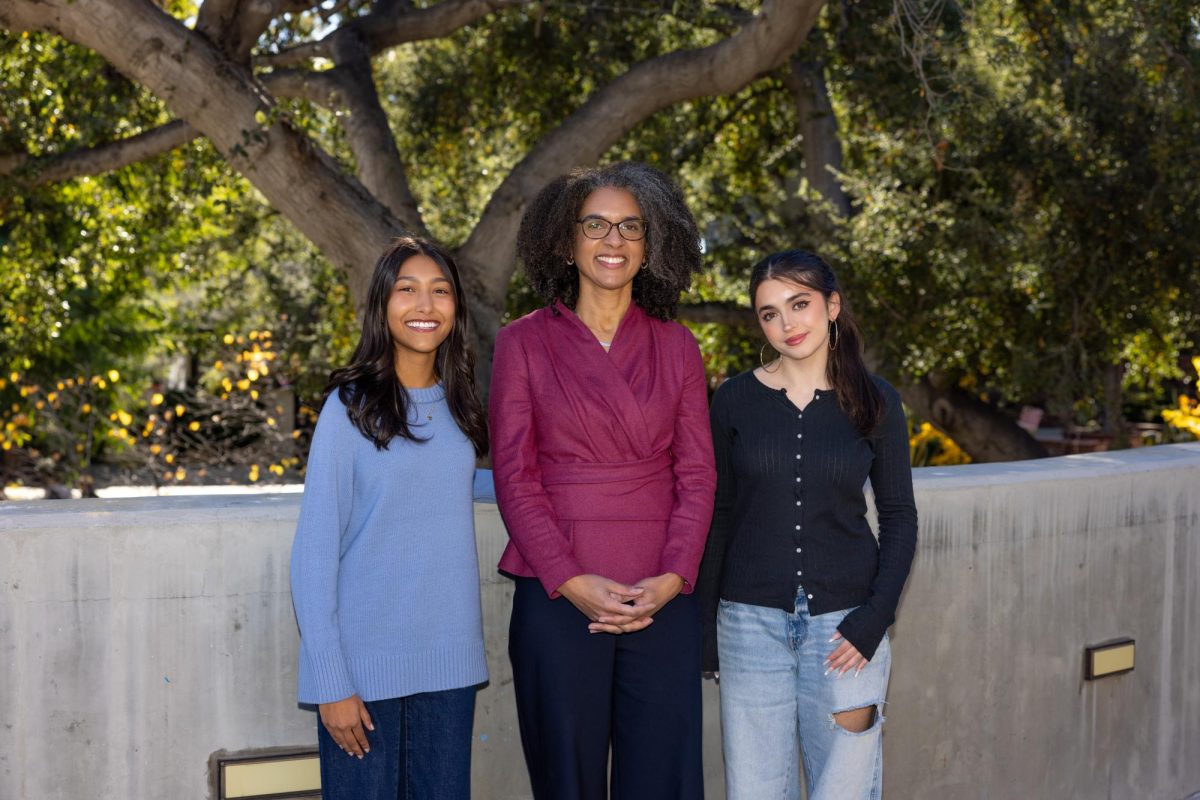

One possible solution to this issue could be grade norming, a process in which teachers who are teaching the same course come together to establish a consistent and shared understanding of a grading rubric. Teachers independently grade a few tests, essays or other assessments and then compare the scores they awarded to make sure they fall in the same ballpark. Conducting this process before and possibly during the grading of major assignments would help standardize fair evaluations and reduce the aspect of luck in a student’s final grade.

The English Department does currently engage in grade norming; however, the impact has been limited, largely due to scheduling obstacles. It is difficult for English teachers to coordinate time to norm or collaborate in their already packed schedule. This is where the administration could try to help by integrating time into teachers’ schedules for them to grade norm, potentially during community time or during Extra Help on a set day. This would provide a defined time for teachers within a department to ensure that their grading is consistent and fair.

Ultimately, Poly must not only acknowledge but also confront that there are consistent grading disparities across multiple departments, which can have an effect on a student’s mental health and their future academic success. A student’s grade should be a reflection of their effort, skill and growth, not the luck of the draw, and implementing grade norming with the help of administration could have a significant impact on reducing grading disparities.