The United Nations, an international organization founded to promote peace, security, and cooperation among countries, was founded on equality. It gives each country, no matter how small, one vote to speak on the outcome of the world. In 2012, 193 nations voted to work together to achieve a set of goals related to the environment and equality called the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and we’ve all heard about them many times here at Poly. The world wants to meet all these goals by 2030, but we are nowhere close to achieving any of them on time.

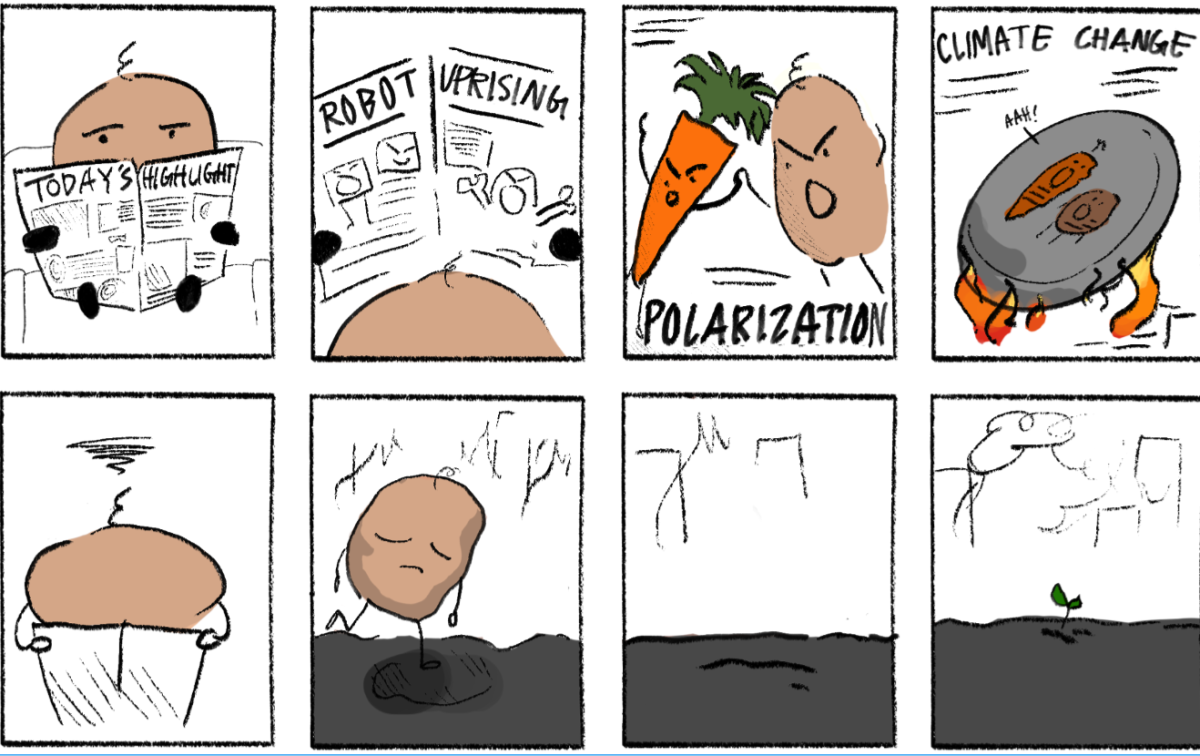

Our country can be doing better. We could set ourselves on the right path, a trajectory where we would not only meet but also exceed all of the expectations laid out by the SDGs. However, the United States is too busy focusing on its own problems to take a look at other countries in need around the world. Our minds are wrapped around how to deal with tariffs, immigration, healthcare and impeachment, so much so that we forget about the state of the world as a whole. The U.S. isn’t interested in taking action to work toward these goals. We are one of five countries that didn’t submit an SDG action plan for the future. This lack of engagement from one of the world’s most influential nations signals a broader issue within the international community regarding the prioritization of these critical goals. Something needs to change within the U.N. for the world to take the SDGs more seriously.

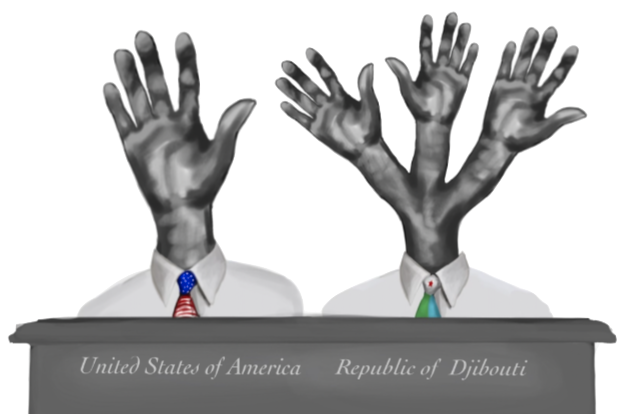

We should start with the U.N.’s voting system. Although each country has an equal voice, no matter how small, the reality is this: the U.S. and other powerful countries use bribes of financial and military aid to sway the votes of smaller nations. For example, the U.S. promised “rich rewards” to nations that would support it before its invasion of Iraq, according to Harvard Business School. The support of these nations helped the U.S. justify their invasion and make it seem more reasonable. Nations that need financial help have no other option than to accept these offers in order to save themselves. They can’t vote to further the improvement of climate change or the development of education-based policies because their governments’ current financial and military needs force them to de-prioritize the long-term effects of climate change, poverty, and lack of resilient infrastructure. By raising the number of votes each small nation has in the U.N., however, they can break free out of this cycle and voice their true opinions regarding SDG-aligning policies without outside influence from countries like China or the U.S.

Because small countries, such as island nations close to sinking under rising sea levels, bear the consequences of climate change the most yet contribute the least to global carbon emissions, it is in those countries’ best interests to end carbon pollution. Thus, by giving them more power within the United Nations, we would start to see the success of more and more policies that prioritize achieving the SDGs, which place a heavy emphasis on climate action. Once these smaller nations reach a certain point of economic stability, the amount of money needed to sway their vote one way or another will significantly increase because the amount of money they receive in a desperate economy has nowhere near the same impact as it would in a stable economy. They will, therefore, be able to prioritize the SDGs before money, putting an end to corruption and the tight, controlling grasp that the U.S. and other powerful nations hold around the world.

Of course, the biggest problem with this proposition is the loss of American power, but that isn’t innately bad. America’s loss of power in this context would also mean that China, Russia, and other major global actors would lose influence. Their loss of power translates to increased power in the hands of residents of small, weak nations. We should trust these people with our planet. We should trust they will push aside avarice because money means nothing without an island to live on or food to eat.

In the current system, the U.N. goals are far from being addressed; while we’ve waited patiently for the 2030 deadline, which continues to inch closer and closer, there has not been significant progress. We’ve given the U.S. a chance to fix the world and strive for a better future, but it hasn’t. It’s time to hand over the reins to countries more willing to tackle these pressing global concerns and give them a platform to do so. Let’s foster an environment where decisions are not based on the will of traditionally powerful nations, and let’s give power to those who want to put the world before themselves.