Pew Research Center

When that final school bell rings in June, the sacred season of summer break begins. Swimsuits replace school uniforms, alarm clocks are silenced and the air smells faintly of both sunscreen and possibility. But, as students scatter toward vacations, internships and naps, a question that nobody tends to think about lingers beneath our relieved, collective sigh: Is summer break ethical?

At first glance, that question sounds absurd. Who wouldn’t want a break from school? But zoom in, and the ethics of this annual pause – who it helps, who it hurts and what responsibilities it brings – get more complicated than you would expect. Summer break should be a time for students to explore personal interests, but not everyone has the same opportunities to do so. For example, factors like socioeconomic status play a huge role in determining what students can do during the break. Poly, as a private institution with a high-achieving and typically well-resourced student body, represents one of the more privileged corners of the American educational landscape. Students’ summers often reflect this reality: international travel, elite academic camps and professional-level internships are all within reach. After asking a few students about their summer schedules this year, freshman Aidan Shih mentioned that he is going to Japan, doing an online internship and writing poetry. Rising sophomore Theodor Faraon mentioned that he is going on a two-week vacation and attending a coding camp.

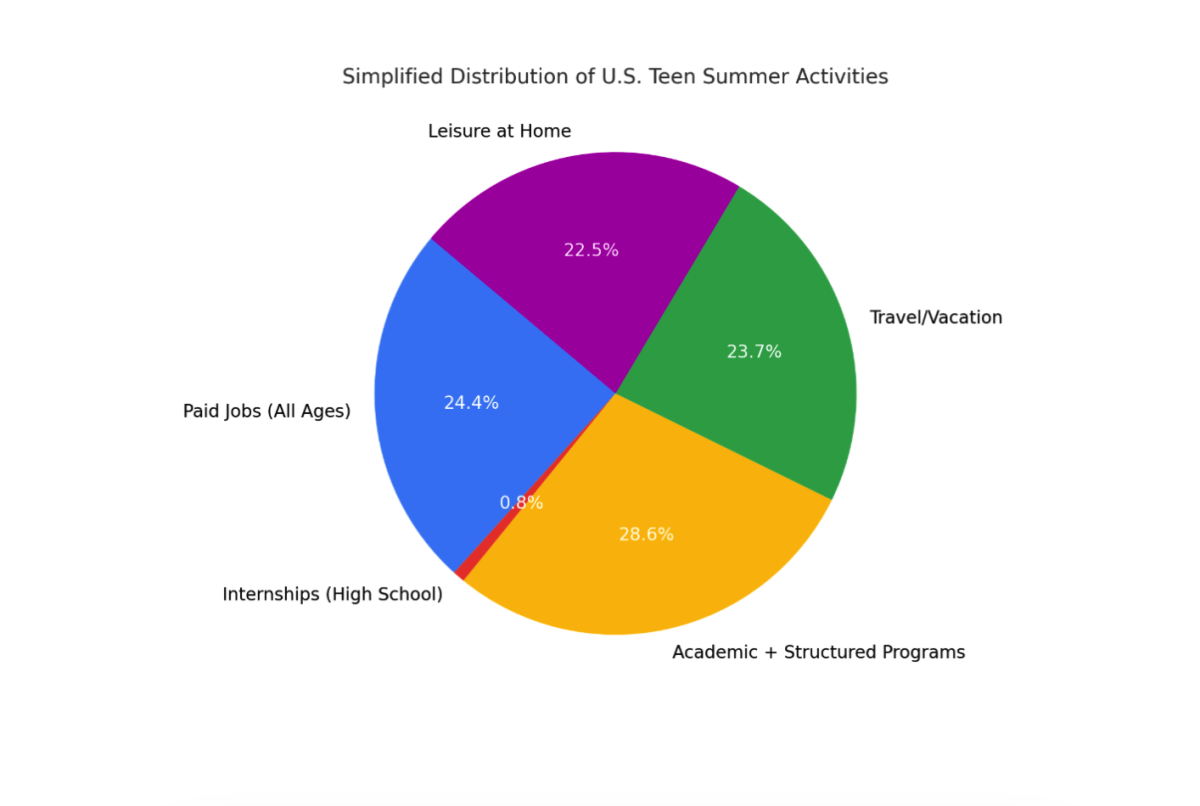

While experiences like these offer incredible opportunities for growth, they also serve as a striking contrast to national data from Pew Research, with 24.4% of all U.S. teens working a paid job during the summer and only 23.7% traveling. Poly students themselves acknowledge this privilege, and their insights provide a rare and valuable window into how even those benefiting most from the system are beginning to question its fairness.

Shih commented, “Everyone has equal time in the summer, but socioeconomic status can be a big influence in providing people with equal summer opportunities. But, all experiences can be meaningful in some ways, despite the cost.” Faraon mentioned, “College inflation nowadays further perpetuates summer inequalities by giving those with access to camps and internships an unfair advantage.”

When we assume that how we spend our summer breaks is purely a personal decision, the ethics get tricky. What happens when your break depends on your zip code, your income or your family situation? Summer break, as it stands today, is time off, but it also quietly perpetuates privilege. For students with greater financial stability or access to resources, summer can be a launchpad: a time to build resumes, strengthen college applications or network through internships. It can also be a time to unwind, whether that means relaxing on the beaches of the Bahamas or exploring the ruins of ancient Rome. For others, summer break is a necessary time to work jobs, care for younger siblings or elderly relatives and shoulder responsibilities that leave little room to even imagine costly travel or academic enrichment.

This divide in how students experience summer raises ethical questions, especially for those who want meaningful opportunities but lack the financial resources or social connections to access them. Do we, as a society, have a duty to provide equal summer opportunities? Should school systems expand access to free programs or summer enrichment, especially for underserved students? If we ignore the disparities, are we complicit in reinforcing them? This ties into the larger issue that freedom without equity isn’t freedom for all. A student may technically be “free” to enjoy summer, but if they lack access, resources or safety, that freedom is theoretical, not real.

To address the inequality that arises during the summer, a multifaceted yet feasible approach is needed, one that focuses on expanding education, economic opportunity and access to resources for students who face greater barriers. This could include increasing access to summer learning programs, offering more summer job opportunities and expanding free public resources like libraries and parks. As an institution, we might provide financial support to qualified Poly students from under-resourced backgrounds so they can attend prestigious summer camps. We could also expand our free summer offerings through programs similar to Partnership for Success!, a program funded and run by Poly and three other local private schools that supports underserved students in the Pasadena Unified School District. Additionally, we should consider increasing financial aid for students attending PolySummer.

After all, that’s what makes summer so unique—it’s the only time of year when our lives truly diverge, when we step into entirely different worlds for a brief moment; but when the school bell rings again, no matter where we’ve gone, we all return to the same desks, the same hallways, as if those differences never existed. So, as you lounge in a hammock or grind through your summer job, also ask yourself: In a world where summer sends us in such radically different directions, what responsibilities do I carry—not just to myself, but to the classmates I sat beside all year—when time, space and opportunity are no longer shared equally?